Localities have previously been required to conduct fair housing planning and document strategies to address barriers to fair housing in an Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice or an Assessment of Fair Housing (AFH). The AFH, required under the Obama administration’s 2015 AFFH rule, was repealed by the Trump administration in 2018, leaving HUD grantees with no specific requirement to conduct fair housing planning. In 2021, HUD announced rulemaking for a proposed planning process similar to what was required to complete the AFH.

Under the proposed rule, localities would complete an Equity Plan, expected to be similar to the AFH in encouraging HUD grantees to take a balanced approach to fair housing planning and to assess fair housing barriers at the local and regional level. A balanced approach includes fair housing actions that support protected classes in moving to resource-rich areas and investments in low-income and racially/ethnically concentrated neighborhoods. This case study series focuses on a mobility program in Buffalo, NY; a series of place-based strategies and investments in the Hill District neighborhood of Pittsburgh, PA; and a regional fair housing planning process conducted by multiple localities in the North Texas region. Lessons from these case studies may be beneficial to localities both before and after the proposed rule is finalized:

Buffalo, NY’s mobility initiative to AFFH: In the Buffalo metro area, a multi-agency, regional initiative is helping low-income households move to resource-rich neighborhoods by providing housing mobility counseling, raising awareness, and creating regional partnerships to enable mobility across multiple jurisdictions. The program has been so successful that it expanded statewide. This case study shares how localities can structure their housing mobility initiatives to help improve racially and economically marginalized families’ quality of life and access to opportunity.

Pittsburgh, PA’s place-based investments to AFFH: The City of Pittsburgh is encouraging placed-based investments in the Hill District, a historically Black neighborhood that experienced decades of disinvestment, economic decline, population loss, and harmful urban renewal projects. A series of city- and community-led planning efforts contributed to targeted public investments in the Hill District that spurred private investments. Ongoing city efforts aim to spur additional private investments and add neighborhood amenities while preserving affordability and protecting long-term residents from displacement.

North Texas Regional Assessment of Fair Housing: Twenty-one localities and housing authorities in North Texas conducted a Regional Assessment of Fair Housing in 2018. This collaboration better positioned its partners to address regional and local fair housing challenges through coordinated knowledge sharing and strategies to advance equity throughout the region. This case study discusses common fair housing issues and offers ideas on how localities can implement a regional approach to develop a joint fair housing plan and pursue shared fair housing goals.

Affirmatively furthering fair housing in Buffalo

Overview

Housing mobility programs address barriers to fair housing choice by helping voucher participants secure housing in resource-rich neighborhoods. This case study describes housing mobility initiatives led by Housing Opportunities Made Equal (HOME) Buffalo, a coalition of civic and religious organizations in the Buffalo-Niagara metropolitan area, an area with deep patterns of racial segregation and income inequality. HOME has been providing support to voucher participants in Buffalo since 1997. It has recently expanded its housing mobility support with the help of grant funding from private organizations and New York State. HOME works with Housing Choice Voucher program participants, public housing authorities, landlords, and other service providers to help program participants find improved housing options in lower-poverty neighborhoods in the Buffalo-Niagara metropolitan area (referred to as Buffalo metro).

Key takeaways

Housing mobility counseling is important for supporting a family’s move: Counseling can help voucher participants acquire more knowledge about the local housing market, understand the different opportunities available, and visualize the necessary steps in the pre-and post-moving process.

Regional partnerships are critical: When multiple public housing authorities operate independently in a highly segregated region, segregation and housing discrimination patterns can be reinforced due to limited information exchange and tenant outreach to promote mobility. A regional and integrated approach to voucher administration can help improve housing mobility substantially.

Landlord engagement improves housing choice and mobility in the long-term: Even with source of income discrimination laws in place and supports for tenants using vouchers, landlords can require high security deposits or credit checks that can have a discriminatory impact against voucher participants who typically do not have the necessary savings or credit history. Outreach and effective engagement with landlords through housing mobility and other programs can help address landlord concerns and provide information about the voucher program and its management. Financial incentives to landlords can also help recruit new landlords and expand housing options for voucher participants.

Description

Segregation in Buffalo and HOME’s efforts

The Buffalo metro is the country’s sixth most segregated large metro area. A fair housing equity assessment report prepared for the region found that the 16 racially and ethnically concentrated areas of poverty (R/ECAP) are all heavily concentrated in Buffalo, which is also where most of the region’s Black population lives. Erie and Niagara counties, which make up the metropolitan area, are majority white. Sixty percent of the area’s white residents live in higher-opportunity areas compared to only ten percent of Black residents.

A 2019 study on voucher usage found that 61 percent of voucher participants with children in the Buffalo metro area lived in high-poverty areas, the highest share among large metros in the U.S. Voucher usage in Buffalo is concentrated in high-poverty neighborhoods despite those neighborhoods having fewer homes that are affordable to voucher participants than in other parts of the metro, including low poverty and high-opportunity neighborhoods. Sixty-one percent of voucher participants with children live in high-poverty areas where only 35 percent of the homes are affordable to voucher participants. In contrast, only eight percent of voucher participants with children live in low-poverty neighborhoods where 28 percent of the homes are affordable to voucher participants.

According to a 2020 report by Poverty and Race Research Action Council, segregation in the Buffalo metro has persisted for decades due to the lack of cooperation between different PHAs in administering the voucher program in the region. Despite a court-ordered desegregation order in 1998, Comer v. Kemp, requiring changes in the voucher administration process in the region, change has been slow.

HOME, a fair housing agency, which led the lawsuit with other civil rights agencies, started the Greater Buffalo Area Community Housing Center (Community Housing Center) from the settlement proceeds to provide housing counseling, housing search assistance, and fair housing training to voucher participants. HOME implemented three housing mobility programs in the last 25 years: Community Housing Center housing mobility support started in 1997; the Greater Buffalo Mobility Assistance Program (MAP), in place from 2020-22; and the Making Moves Program, launched in the last quarter of 2022.

Community Housing Center initiative

The housing mobility services offered through the Community Housing Center mainly provided orientations to voucher participants with children at the PHAs and fair housing education. Through their housing search support, HOME helped interested families who approached them move to census tracts with lower poverty rates – less than 30 percent. According to HOME staff, financial proceeds from the settlement and any private grants HOME received intermittently helped provide security deposits to newly approved voucher participants during their first housing search. 1 However, the program produced limited geographic dispersion mainly due to the lack of cooperation from PHAs administering vouchers in the surrounding counties and HOME’s limited capacity.

Long-standing patterns of segregation and housing discrimination also restricted movement of voucher-assisted families to the suburbs. Even though the City of Buffalo banned source of income discrimination against voucher participants and other benefits recipients as early as 2006, the lack of similar protections in the surrounding Erie County until 2018 (and in the State of New York until 2019) impeded housing mobility efforts at the regional scale. In 2019, HOME paid renewed attention to providing financial assistance and support to families interested in moving from the City of Buffalo to higher-opportunity areas in the suburbs. At that time, Enterprise Community Partners asked HOME to lead MAP in the Buffalo region.

Mobility Assistance Program – Background

HOME partnered with the three agencies responsible for administering the voucher program in the Buffalo metro – Rental Assistance Corporation, Belmont Housing Resources, and the Buffalo Municipal Housing Authority – and initiated a two-year contract in October 2020 with Enterprise Community Partners to implement MAP. The program helped families with children move to “child opportunity areas” in Erie and Niagara counties that had lower poverty, unemployment, crime rates, and relatively high-performing schools (GIS platform showing eligible areas). Using MAP program funding, HOME improved its staff capacity from one to four dedicated staff members providing pre- and post-move support to eligible families.

According to the HOME housing mobility staff, HOME began its mobility counseling by sharing outreach letters to all their voucher participants with children through PHA partners. At the PHAs’ fair housing and voucher briefings for all their voucher participants, HOME staff invited voucher participants with children to apply to the MAP program. They helped them fill in an intake form gathering the family’s income, background, and housing type and location preferences. Mobility counselors then helped families throughout the housing search process, including assisting them to complete their lease applications and communicating with prospective landlords on their behalf. MAP also provided their program participants $300 for moving expenses and $700 for a security deposit.

Mobility Assistance Program – Implementation

In the second year of MAP’s implementation, HOME partnered with banks and other nonprofits to expand existing counseling programs to include financial literacy, job training, and nutrition education programs. HOME expanded the MAP program to all voucher participants instead of just families with children. It also provided enhanced payment support toward moving expenses and security deposits, often compensating for all moving costs.

HOME’s mobility coaches connected families with movers, made payments to the moving company on the families’ behalf, and checked in with the family within ten days of the move and with their landlord within two to three weeks after the move. To the extent possible, counselors offered post-move support, such as referrals for education and job counseling. Also, they referred families to mediation services if there were any landlord-renter conflicts.

HOME started landlord recruitment under MAP to expand housing opportunities in the suburbs where landlords were either unaware of the voucher program or had reservations about participating in it. They also offered interested landlords group counseling and education programs to explain the voucher process. In many cases, they liaised between the landlords and the PHA caseworkers to help address landlord concerns related to delayed payments or inspections. To incentivize landlord participation, HOME offered grants of up to $5,000 from the Housing Quality Improvement Fund to landlords to finance property improvements and meet HUD housing quality and safety standards.

Making Moves Program

At the end of HOME’s two-year MAP contract with Enterprise Community Partners in October 2022, New York State launched the Making Moves Program, a new statewide program closely modeled on the MAP program, and contracted with HOME to serve the Buffalo region. Under the Making Moves Program, as with MAP, families with young children are prioritized for assistance. The Making Moves Program also increased financial assistance for moving expenses from $300 to $700 and for security deposits from $700 to $1,200. Under the Making Moves Program, HOME required families to attend housing counseling and training programs to receive security deposit payments. This requirement and the offer of moving support to all families with children, not just those moving to higher-opportunity areas, improved program participation.

Process and timeline

1998: A class action lawsuit, Comer v. Kemp, brought by a coalition of civil rights advocacy organizations and led by HOME, Buffalo, resulted in court-ordered desegregation and the start of housing mobility services through the Community Housing Center.

2005: End of settlement funding support for the Community Housing Center. HOME pursued other funding support and reconfigured mobility support with reduced incentives.

2020: Launch of Greater Buffalo Mobility Assistance Program (MAP).

2022: Launch of the Making Moves Program, the state-funded mobility counseling program to help voucher participants (specifically, families with children) find homes.

Outcomes

Over time, HOME has built its capacity to help voucher participants exercise more choice in their housing decisions. Since starting the Community Housing Center in 1998 to 2020, HOME and their partners helped 3,000 families find housing and provided housing mobility information to nearly 5,000 families. HOME expanded the housing mobility services they offered under the Community Housing Center when they rolled out the Mobility Assistance Program (MAP) in 2019. Whereas under the Community Housing Center program, HOME only assisted new voucher participants in their first home search, under MAP they also assisted existing voucher participants with children.

According to the information shared by HOME staff during a personal communication on May 1, 2023, the MAP program had an annual target of helping 80 families move into high-opportunity areas. But several factors, primarily related to the COVID-19 pandemic, limited the number of moves HOME could support. Social distancing, reduced meeting frequency, and a smaller number of participants in group counseling and briefing sessions made enrollment in the program difficult in 2020. At the same time, fewer homes were available to voucher participants due to the state moratorium on housing evictions.

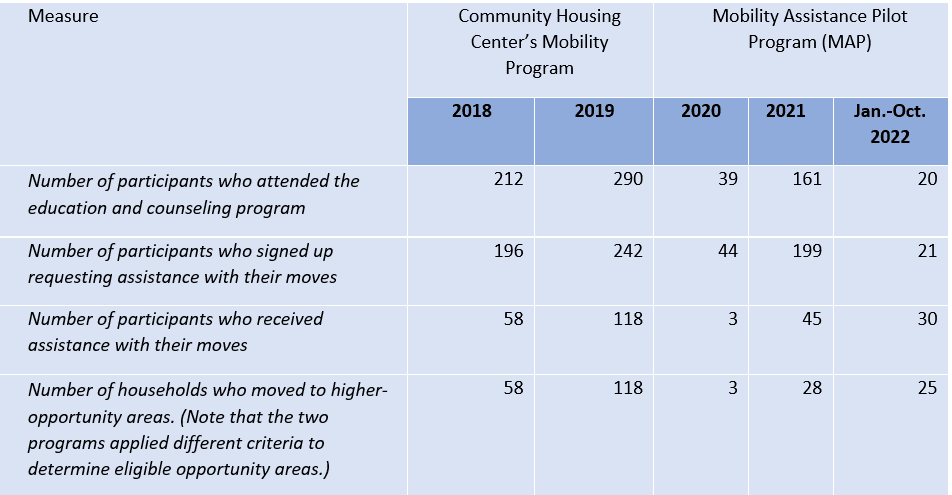

As shown in the table below, Community Housing Center’s mobility program was able to help more families move compared to MAP. For example, in 2019 alone, a high number of voucher participants who attended the Community Housing Center’s counseling programs requested assistance in their moves; nearly half of those who requested assistance received it, and all of them were able to move into qualifying opportunity areas identified by the Community Housing Center. Under MAP, while many families requested assistance in finding a unit, less than a third – 78 of 264 households – received mobility assistance, and only 56 of the 78 assisted households moved to the MAP-designated child opportunity areas. This was primarily due to pandemic-induced housing market conditions and limitations but also because there were lower requirements for qualifying opportunity areas under the Community Housing Center’s mobility program compared to MAP. Additionally, MAP’s involved program approach required more staff hours and capacity.

As a result of this approach and collaboration with PHAs and landlords, MAP achieved greater geographic dispersion into neighborhoods outside of Buffalo. Nine new landlords enrolled under MAP, some of them bringing more than a hundred rental units into the program, according to HOME staff.

Source: Data provided by HOME via personal communication dated May 16, 2023

Despite limitations in MAP’s implementation, an evaluation funded by Enterprise Community Partners in 2022 found that MAP achieved considerable success in meeting its objectives. The evaluation found that while 70 percent of MAP participants were living in neighborhoods with poverty rates of 20 percent or greater, only 10 percent did so after the move. The average poverty rate of the neighborhoods participating families moved into through the program was 12 percent, marking a significant change in neighborhood conditions for participating families.

Due to the short duration of MAP’s implementation, the evaluation did not measure health and well-being outcomes. However, the study found that participating families, in general, were happy with their new neighborhoods: 86 percent of families reported feeling happier, and 90 percent said their family’s overall health improved after the move. Families also reported high satisfaction with the higher-performing schools their children were now attending.

HOME’s staff reported that implementing MAP helped them make new connections with landlords and other players and understand barriers to voucher utilization in the Buffalo region better. Within the third quarter of implementing New York State’s Making Moves Program, HOME staff reported improved program participation due to process efficiencies they created based on their experience implementing the MAP program.

Policy significance

HOME’s efforts in Buffalo to improve mobility for voucher participants show the complexity of administering such programs and the various factors that may limit the number of families they serve. However, the case also illustrates how long-term housing mobility initiatives can build on previous successes and deepen landlord and tenant engagement to improve outcomes for voucher participating families with children.

HOME’s approach to mobility programs provides comprehensive support to voucher participants after they receive a voucher and after their move through effective and regular communication. HOME’s achievement of improved collaboration with PHAs and increased moves to opportunity areas suggests potential for addressing housing segregation in the Buffalo metro. The scale up of the program as a statewide effort also shows promise for continued support for mobility programs. Similar programs by regional HOME organizations in other cities, including Richmond, Virginia; Cincinnati, Ohio; and the Creating Moves to Opportunity initiative in Seattle-King County, Washington, are also encouraging steps toward improving outcomes of voucher programs.

Related resources

A City Divided: A Brief History of Segregation in the City of Buffalo. This policy report explores the history of segregation in Buffalo and offers policy suggestions for the years ahead.

A Review of the New York State Housing Mobility Pilot. Funded by Enterprise Community Partners, this evaluation of the Mobility Assistance Program in Buffalo, Long Island, and New York City was conducted in 2022 by the Poverty and Race Research Action Council (PRAAC) and Mobility Works.

Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice. This analysis was prepared in 2020 for the City of Buffalo, Erie County, and the towns of Amherst, Cheektowaga, Tonawanda, and Hamburg.

Child Opportunity Index (COI) | diversitydatakids.org. The Child Opportunity Index (COI) is built on 29 neighborhood-level indicators ranging across education, social and economic, and health and environment domains that can have an impact on child health and development outcomes.

Fair Housing Equity Assessment. This assessment prepared in 2014 by the University of Buffalo was part of the One Region Forward Initiative to expand opportunity and sustainable economic development in the Buffalo Region.

Housing Mobility Programs in the US 2020. A compendium of housing mobility initiatives across the country prepared by the Poverty and Race Research Action Council (PRAAC) and Mobility Works.

The Legacy of Buffalo’s Landmark Housing Desegregation Case, Comer v. Kemp. This report discusses how the 1989 class-action suit, Comer v. Kemp, would change the face of government-assisted housing and patterns of racial segregation which dated back to the early twentieth century.

Where Families with Children Use Housing Vouchers: A Comparative Look at the 50 Largest Metropolitan Areas. This study of metropolitan segregation in U.S. metropolitan regions analyzes the neighborhood characteristics of voucher-assisted families with children.

Footnote

[1] Personal communication with Housing Opportunities Made Equal (HOME) staff member, Buffalo, New York (May 1, 2023, and May 16, 2023).

Pittsburgh, PA's place-based investments in the Hill District

Overview

The City of Pittsburgh is using place-based strategies in disinvested neighborhoods to attract new investments without displacing current residents. This case study focuses on a series of planning efforts focused on stabilizing and revitalizing Pittsburgh’s Greater Hill District (Hill District). The Hill District includes several historically Black neighborhoods that experienced decades of disinvestment, high rates of vacancy, and population loss. A series of urban renewal projects demolished homes and businesses and disconnected the district from Pittsburgh’s economic center. The Hill District has experienced a surge of public and private investment in recent years, mainly in line with the recommendations outlined in the neighborhood’s community-driven 2011 Master Plan.

Key takeaways

Planning and place-based investments that incorporate fair housing principles can help localities address past harmful plans and policies. The City of Pittsburgh has made beneficial place-based investments in the Hill District to help address the negative impacts of past exclusionary and discriminatory plans and policies, including building a freeway cap park that reconnects the neighborhood to downtown and a new grocery store in an area that had previously been a food desert.

Localities and community partners can negotiate for place-based investments that benefit existing residents. Community stakeholders in the Hill District were able to negotiate the city’s first-ever community benefits agreement, which committed the Pittsburgh Penguins to provide financial and non-financial resources to benefit existing Hill District residents as part of its redevelopment of a part of the Lower Hill neighborhood.

Description

The Hill District in Pittsburgh comprises seven predominantly Black neighborhoods: Crawford Square, Bedford Dwellings, Uptown/The Bluff, Terrace Village, Upper Hill, Middle Hill, and Lower Hill. Once a thriving and culturally diverse area with many small businesses and neighborhood amenities, it began to decline in the 1920s when a new road rerouted traffic around the neighborhoods.

The Lower Hill neighborhood underwent significant changes in the 1950s and 1960s as a result of several urban renewal projects. These projects involved demolishing buildings and constructing new public housing, which displaced thousands of people and hundreds of businesses from the area. As an example, the development of the Pittsburgh Civic Arena in 1961 razed an 80-block area and displaced 800 residents.

The Hill District suffered decades of disinvestment, partially due to the steel industry’s collapse, which contributed to job and population loss. By 2013, just 47 percent of Hill District parcels were occupied, while 45 percent were vacant lots and seven percent were vacant buildings. From 2010 to 2020, Pittsburgh’s Black population declined by more than 13 percent, while the city’s shrank by less than one percent.

Planning in the Hill District

Since 2009, several city- and community-led planning processes have sought to guide and encourage revitalization efforts in the Hill District to promote housing choice and neighborhood amenities for long-term residents and prevent further displacement. Contributing to the planning efforts was a community benefits agreement negotiated as part of the Pittsburgh Penguins’ redevelopment of an area in the Lower Hill neighborhood for a new arena and other mixed-use projects.

In 2008, in exchange for developing the new arena in Lower Hill, the One Hill Coalition, representing around 100 community stakeholders, negotiated the community benefits agreement with the Pittsburgh Penguins, the Sports and Exhibition Authority, the Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh, the City of Pittsburgh, and Allegheny County. The agreement funded the development of a master plan for the Hill District, among other resources.

Since the community benefits agreement, multiple fair housing and community development planning processes have focused in part or wholly on the Hill District. Additionally, the city, Urban Redevelopment Authority, and other stakeholders made several investments in the Hill District that align with recommendations that emerged in these planning efforts.

Fair housing activities

In 2013, the Commission on Human Relations, which conducts fair housing enforcement and education in Pittsburgh, established the AFFH Task Force to help the city assess its impediments to fair housing choice and develop policy recommendations that affirmatively further fair housing. The creation of the AFFH Task Force was a recommendation from the city’s 2012 Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice. The Task Force comprised representatives from the City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, the HUD, the city and county’s housing authorities, two other jurisdictions in Allegheny County, and other groups that promote fair housing. The Task Force’s final report, released in 2019, called for increased investment and a more equitable distribution of Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) dollars in the Hill District and other predominantly Black neighborhoods.

In 2016, and again in 2020, Pittsburgh completed additional analysis of citywide barriers to fair housing and housing choice. Each report identified past or planned investments in the Hill District to expand housing options.

Community development activities

In 2011, the Hill District’s first master plan was completed and identified “family-friendly housing” as a key community goal to be achieved through supports for homeowners and tenants, including home repair and mortgage programs and education on tenants’ rights, and prevention of the displacement of existing residents. The plan also called for developing a strategy for improving vacant properties. The city began updating the plan in 2020.

Other activities included the 2013 Hill District Vacant Property Study, produced by the community-led Hill District Consensus Group, which recommended 1) properties to be protected, improved, or demolished, and 2) a housing strategy for the Hill District to promote resident and neighborhood stability. The 2015 Centre Avenue Redevelopment and Design Plan outlines community-supported strategies to transform the Centre Avenue business corridor, which experienced widespread demolition, including an increase in economic development and the addition of a variety of housing types. In 2016, the city and the Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh received a $500,000 Choice Neighborhood Planning Grant to plan for the revitalization of the Hill District’s Bedford Dwelling public housing complex (The city subsequently applied for but did not receive an implementation grant to replace 100 units in the complex and add 200 new mixed-income units in the Hill District.)

Place-based investments in the Hill District

To help address challenges of vacancy and displacement, the City of Pittsburgh and its partners have taken steps to increase place-based investments in the Hill District to improve neighborhood and housing conditions for existing residents and attract new residents.

In 2015, the Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh established a tax increment financing district in the Lower Hill neighborhood, revenue from which would be split equally by the Pittsburgh Penguins and the Greater Hill District Neighborhood Reinvestment Fund (Reinvestment Fund). The Reinvestment Fund was established via the Community Collaboration Implementation Plan, an agreement between the community and redevelopment partners regarding the development of 28 acres in the Lower Hill neighborhood that aims to implement recommendations in the 2011 Greater Hill District Master Plan. Eligible uses of the Reinvestment Fund include rental and homeownership assistance and business, workforce, and community development activities in the Greater Hill District. In September 2021, First National Bank, which is building its new headquarters in the Lower Hill neighborhood, contributed $7.2 million to the fund.

Other investments in the Hill District have included the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s (URA) purchase of the Centre Heldman Plaza and reaching an agreement for a new grocery store to move into the space. Support for the grocery store, a priority for community members, included $1 million from the Pittsburgh Penguins and $1 million from the Pittsburgh URA as part of the community benefits agreement.

The city’s three-acre freeway cap park connecting the Hill District to Downtown is another notable place-based investment. Completed in 2022, the project was a partnership between the City of Pittsburgh, the Sports and Exhibition Authority, PennDOT, and the Federal Highway Administration to repair the broken link created when authorities built that part of the interstate in the 1950s and 1960s. Then, in 2023, Pittsburgh received a $11.2 million Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity grant to make streetscape, transportation, and accessibility upgrades in the Hill District.

Pittsburgh also targeted CDBG, HOME, and other funds for a variety of housing activities in the Hill District in the past decade, including improvements to the Allegheny Union Baptist and Dinwiddie Street public housing complexes, the construction of new rental and owner-occupied homes, and rehabilitation of owner-occupied homes. The Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh also implemented a façade improvement grant program for property owners in the Hill District and other neighborhoods receiving additional public investments in housing.

Process and timeline

2008: Hill District community stakeholders negotiated a community benefits agreement with the City of Pittsburgh, the Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh, and other partners to promote more equitable investment in the neighborhood.

2011: The city completed the Hill District’s first master plan, which helped guide future public and private neighborhood investments.

2013: The city established the AFFH Task Force based on recommendations in its 2012 Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing.

2014: The Greater Hill District Neighborhood Reinvestment Fund was established to invest tax revenue generated by new development in the Lower Hill neighborhood into the broader Hill District.

2019: The AFFH Task Force concluded a multi-year process to develop fair housing recommendations for the city council, including more equitable investment of CDBG dollars in the Hill District and other historically Black neighborhoods.

2020: The city started its process to update the 2011 Greater Hill District Master Plan, which is ongoing as of June 2023.

2021: The Greater Hill District Neighborhood Reinvestment Fund received its first installment of $7.2 million.

2021: The Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh reached an agreement with Salem’s Market to open a grocery in the Hill District, expected in fall 2023.

2022: The city completed a three-acre freeway cap park project to reconnect the Hill District to downtown.

Outcomes

After decades of disinvestment and the systematic removal or neglect of homes and businesses in the neighborhood, various targeted and complimentary planning efforts and place-based investments have begun to yield results in the Hill District. In addition to the freeway cap project and mixed-use development around the Pittsburgh Penguins’ new arena, the Hill District saw the completion of several housing projects.

Accomplishments noted in the city’s 2020 Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice include the funding of three Low Income Housing Tax Credit rental projects from 2015-2016, including Dinwiddie IV (23 new units), Addison III (52 mixed-income units that replaced older public housing), and miller Street Apartments (36 units). In 2018, a 40-unit affordable rental project with ground floor retail was built along the Hill District’s main commercial corridor.

Also in 2015, the URA supported the rehabilitation and preservation of 44 affordable units in the Allegheny Union Baptist apartments, including three accessible units for people with disabilities. No tenants were displaced from the complex due to construction, though authorities moved some to other units at no cost.

In 2016, the URA constructed eight new homes for owner occupancy, and in 2019 it provided $105,000 in grants to Rebuilding Together to support the rehabilitation of eight owner-occupied units in the Hill District.

According to a market analysis conducted as part of the update to the Greater Hill District Master Plan, the neighborhood has seen the addition of over 400 affordable units from 2010 to 2021 and is beginning to see an uptick in new market-rate units, including new construction and rehabbing of existing units/ After surging early in the COVID-19 pandemic, multifamily vacancy rates declined to 5.7 percent in the second quarter of 2021 and are now similar to rates for Pittsburgh overall. The report also noted that the Hill District saw the opening of its first newly constructed market-rate apartment building in over 50 years.

Policy significance

Pittsburgh’s efforts in the Hill District reflect part of a balanced approach to fair housing planning. Through targeted planning and investments, Pittsburgh and its partners have recently expanded housing choice in the neighborhood and economic opportunity for its residents. Pittsburgh offers lessons to other localities aiming to enable protected classes living in formerly disinvested areas to remain in those neighborhoods and potentially benefit from new public and private investments. The Hill District also demonstrates the importance of community members’ involvement in planning for neighborhood revitalization, the potential for carefully crafted community benefits agreements to guide investment decisions, and the need for mechanisms like the Neighborhood Reinvestment Fund to ensure residents harmed by past disinvestment may benefit from future private investment as the neighborhood changes.

Additional information

Greater Hill District Master Plan. This plan from 2011 was the area’s first master plan.

Fair housing barriers and strategies to address them in the Hill District and Pittsburgh as a whole can be found in the city’s 2015-2019 Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice and in 2020-2024 Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice.

Policy Recommendations of the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Task Force. This document provides the AFFH Task Force’s 2019 recommendations for the City of Pittsburgh.

North Texas regional Assessment of Fair Housing

Overview

In November 2018, 21 North Texas localities and housing authorities conducted a regional Assessment of Fair Housing (AFH) for the North Texas Region (see Figure 1 for a list of participating jurisdictions). By collaborating, the participating localities created a data-driven, shared knowledge of fair housing inequities, better positioning themselves to address local and regional housing challenges by creating a set of coordinated strategies to advance equity throughout the region.

This case study examines the strategies and process by which this group of cities and housing authorities in North Texas collaborated to conduct its joint AFH.

Background

In 2015, HUD released an updated rule interpreting and implementing the “affirmatively furthering fair housing” (AFFH) requirements of the Fair Housing Act. The new rule required all jurisdictions receiving funding from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to conduct and submit an Assessment of Fair Housing study every five years to identify barriers to fair housing in their communities, as well as disparities in housing needs and access to opportunity. (Read more about “Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing.”) Federal funding was contingent on meeting the AFFH rule requirements. HUD guidance recommended jurisdictions conduct joint assessments or regional collaborations, but collaboration was not mandatory.

The AFFH requirement was suspended in 2018 and then removed in 2020. Despite these changes, the North Texas Region chose to continue its assessment of housing inequality. In doing so, they made clear their commitment to address fair housing concerns and learn about the spatial layout of segregation in the region.

Key takeaways

The collaborative process for developing a regional AFH was crucial for setting fair housing goals and priorities for the entire region. Without this broader lens, local goals and policies would likely have been inherently narrower in scope and less likely to be effective at addressing fair housing and access to opportunity.

The data and research analysis helped create an informed and deeper understanding of the regional fair housing landscape that could have only been possible through a collaborative effort.

Coordinating with multiple counties or cities may seem more expensive and time-intensive, but hiring consultants or outside experts may actually result in a more streamlined process. By hiring researchers from a local university, the region was also able to take advantage of relatively cheaper expertise, while increasing local knowledge.

Conducting a regional AFH avoids duplication of efforts and improves knowledge sharing. (Source)

Description

In November 2018, the North Texas Region published 21 Assessments of Fair Housing (AFH), one assessment for each participating city or public housing authority. The overarching North Texas Regional Housing Assessment (NTRHA) is a 392-page report that gives in-depth information on the current state of the region’s housing, highlights challenges and barriers to fair housing, and sets goals and strategies to affirmatively further fair housing in North Texas.

Figure 1: Participating jurisdictions

The AFH development process (described in more detail in “Process”) revealed seven preeminent fair housing issues:

- Geographic inequality: The nonwhite and low-income populations are concentrated in Dallas. Similarly, the rate of housing problems (e.g. lack of affordable, accessible housing and access to proficient schools or transit) remains greater in Dallas than throughout the region as a whole.

- Racial/ethnic inequities: Black and Latinx households in the region face housing problems and cost burden challenges at a higher rate and with greater geographic dispersion than do white households. The data suggest that nonwhite households have lower access to opportunity than white households.

- Proliferation of racially/ethnically concentrated areas of poverty (R/ECAP): The number of R/ECAPs in Dallas doubled over the last 26 years, with persistent patterns of poverty present in south and west Dallas. While some R/ECAPs dissipated over time, two-thirds of R/ECAPs identified in 1990 retain their designation.

- Growing segregation: The data shows an increasing level of nonwhite/white segregation characterized by clear spatial patterns.

- Source of income discrimination: The data suggests that the prerogative of landlords to refuse voucher holders affects the residential pattern of housing choice voucher families and the concentration of poverty.

- Growing affordability pressure: Home prices, apartment rents, and property taxes continue to rise rapidly and exceed the capacity of many residents to afford housing, especially households with income at or below 30% of the area median income (AMI), persons with disabilities, persons living on fixed incomes, and single-parent families with small children.

- Transportation/employment: Lower-income residents have limited access to affordable housing in proximity to good jobs with better wages. The lack of affordable, reliable transit options worsens this problem.

The AFH also introduced six substantive and procedural fair housing goals that are designed to address the identified issues, foster collaboration within the region, and affirmatively further fair housing (see “Outcomes”).

Process and timeline

In January 2016, the group of 21 Dallas-Fort Worth entities (see Figure 1 above for the full list) formed a working group to respond to HUD’s AFH requirement. While the working group had previously worked together on housing policy, this project was far more substantial and necessitated each entity’s active participation to fix the region’s shared challenges. By October each jurisdiction within the working group submitted a Memorandum of Understanding, confirming their participation in the regional AFH.

The regional working group identified the City of Dallas as the lead entity, a procedural requirement for regional AFHs. The North Texas Regional Housing Assessment (NTRHA) officially launched in January 2017 and was conducted in three phases: community outreach, data analysis, and the formulation of fair housing goals to address the issues identified (described in detail below). The NTRHA contracted the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA) to conduct the assessment due to its unique public policy and data analysis expertise and familiarity with the region’s housing market. The University led all facets of the AFH, including the research design, analysis, and reporting. University researchers also conducted the AFH’s community engagement activities, including additional surveys and interviews to supplement the tools and data provided by HUD. UTA also spearheaded the composition of the final AFH.

The cost of the NTRHA was split among the participating jurisdictions based on their respective CDBG allocations.

Figure 2: Timeline

Phase 1 – Community Outreach (February 2017)

The official community engagement process began with the launch of the NTRHA website in February 2017. The website, which was created with a plug-in that allowed it to be translated into over 100 languages, provided the general public with information on the AFH process, relevant presentations, and project updates, as well as updated times and locations of public meetings and focus groups.

UTA researchers facilitated the NTRHA’s community engagement and outreach activities, rather than city officials facilitating these efforts, so community members would feel more comfortable openly sharing firsthand experiences, knowledge, and criticism. The researchers engaged community members, stakeholders, and subject matter experts using a variety of strategies, including public meetings, focus groups, consultations, and surveys, even updating and creating tools throughout the process to respond to community needs.

Surveys opened in March and were available for over a year. There were three rounds of surveys, the first of which asked respondents to share their views, concerns, priorities, and level of satisfaction related to fair housing and quality of life issues, like health and transportation. The second round of surveys also included questions to capture socio-demographic information, tenure, and employment status. The final survey was further expanded to include questions about fair housing enforcement.

The survey was followed by focus groups, two rounds of public meetings (38 meetings for the City of Dallas alone), and individual consultations, which ran throughout the project. (See Figure 3 for a full list of tools used throughout the public participation process.) These various engagement strategies were used to gain insight into fair housing barriers existing in the city and region. The findings from these community engagement practices were then reviewed by a technical advisory board of experts and used to help formulate fair housing goals.

Figure 3: Strategy breakdown

Phase 2 – Data Analysis (September 2017)

As part of the requirements for final AFH submission, UTA conducted quantitative analyses of both HUD and locally-collected data describing patterns of segregation affecting groups with protected characteristics. They examined the intersection of poverty, transportation, segregation, and housing. Their study was informed by the stakeholder and expert knowledge collected in Phase 1, and also focused on racial and ethnic segregation, the concentration of poverty, and housing problems for families with children, seniors, and persons with disabilities and limited English proficiency, as well as other protected classes.

The data analysis process culminated in the region finding seven preeminent fair housing issues.

Phase 3 – Formulation of Fair Housing Goals (May 2018)

In this phase, UTA researchers collaborated with staff from participating entities to identify priorities for action based on the data analyses from both the HUD provided data and the data collected through the community outreach efforts. These action items then informed fair housing goals to address these issues (see “Outcomes” for more information).

Outcomes

The AFH revealed a stark geography of inequity unveiled by the AFH resulting from a growing racial ethnic and economic segregation, racial/ethnic inequities, affordability pressures, and systemic barriers to accessing opportunities. To respond to these challenges, the AFH introduced the following six fair housing goals to affirmatively further fair housing. These goals are meant to foster collaboration within the region, acknowledge and address geographic inequalities, and to be both substantive and procedural. The goals are to:

- Increase access to affordable housing in high opportunity areas

- Prevent loss of existing affordable housing stock and increase supply of new affordable housing, especially in higher opportunity areas

- Increase supply of accessible, affordable housing for persons with disabilities

- Make investments in targeted and segregated neighborhoods to increase opportunity while protecting residents from displacement

- Increase services for residents of publicly supported housing and maintain and improve the quality and management of publicly supported housing

- Increase access to information and resources on fair and affordable housing

The AFH process had a number of benefits beyond just producing a report. For example, the City of Dallas has started to work in a more collaborative way across department lines and the city formed cross-functional teams with representation from multiple departments to achieve goals and remove silos. The data collected from the AFH is also helping make more informed decisions. The AFH process pushed the city to continue to develop revitalization strategies for R/ECAP and blighted areas and to review Housing Policy to verify that the needs of lower-income residents were being met.

To advance its fair housing goals, the City of Dallas also established an Office of Equity in October 2018. While the report suggested that there might be promising initiatives such as the housing policy proposed by the Office of Equity and Human Rights, to date there is little publicly accessible information about these efforts. Although this report provided a path towards greater equity in the region, the future use of the process is uncertain due to the rollback of the AFH requirement by the Trump administration.

Policy significance

Working as a region made it possible to more deeply understand the region’s housing problems and develop six housing goals to address these issues and foster continued regional collaboration. The regionally collaborative approach of this AFH proved helpful in several ways for the North Texas Region. Firstly, housing policy often has regional implications. Research has shown that the most fragmented regions in the US have the greatest degree of regional and racial inequity. Similarly, across the country, segregation is increasing at the regional level and is less severe when examined at the city or local level. In order to address issues of segregation and fair housing at the regional level, cities and housing authorities must collaborate on a regional level.

Finally, although HUD no longer requires that jurisdictions submit extensive AFH plans, examples like this one may be useful in the future. The Biden administration has signaled its intention to reinstate the rule and just after taking office, President Biden signed an executive order, mandating HUD to examine the effects of the previous administration’s signature housing policy, “Preserving Community and Neighborhood Choice.” The lessons learned during the North Texas process can help inform refinements and revisions as the next iteration of the AFFH rule takes shape.

Additional information

2018 Analysis of Impediment: North Texas Regional Housing Assessment. City of Frisco.

Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing. US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Assessment of Fair Housing Tool for Local Governments. PRRAC.

Briefing on the Regional Assessment of Fair Housing. City of Dallas.

Data and tools for Fair Housing Planning. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Executive Summary: North Texas Regional Housing Assessment. City of Dallas.

North Texas Regional Housing Assessment. City of Dallas.

North Texas Regional Housing Assessment. City of Plano.

Racial and economic segregation in Dallas is getting worse [Editorial]. The Dallas Morning News.