Engaging the community in a local housing strategy

December 12, 2024

Image credit: Alfred Castillo from Pexels

Housing policy and development decisions impact all members of a community. However, evidence suggests that the processes used to gather public input on local decisions are often dominated by subsets of people who do not necessarily represent an entire community. This can perpetuate inequitable outcomes and hamper local housing policy or land use reform efforts. Housing leaders often acknowledge this challenge but need practical examples of ways to improve local community engagement approaches. LHS offers a range of such materials to help local leaders assess and improve their engagement strategies.

What is community engagement?

Broadly stated, community engagement refers to interactions between an entity with decision-making authority and those likely to be affected by its decisions. When done well, community engagement can help governments ensure that their decisions properly address the lived experiences of those impacted. Conversely, community engagement risks amplifying the perspective of an unrepresentative subset of well-off community members if not undertaken carefully.

Source: Housing Solutions Lab

What are the main barriers to equitable engagement?

Public events like meetings, town halls, presentations, or workshops are technically open and available to anyone who wants to engage. In practice, older, white homeowners are often overrepresented, and renters and people of color are often underrepresented. These disparities are facilitated by barriers that arise from the personal circumstances of the public and the limitations of current government processes, summarized in the table below.

Source: Housing Solutions Lab staff analysis

For a detailed discussion of what community engagement is, what the barriers to equitable engagement are, and how they can skew who participates in community engagement, read Part 1 of our community engagement brief.

How can cities improve community engagement?

Some common tools governments use to engage their constituents include task forces, community meetings, partnerships with community-based groups, and web-based platforms. However, the efficacy of any given tool depends on the engagement process’s end goal, the type of information governments need from communities, and the resources they can dedicate to engagement efforts.

Designing meaningful engagement

Define the scope of the planning process

Being clear about the scope of the housing strategy process will make it easier to engage the community in a transparent and accountable way. Leaders may pose the following questions to help them define the process:

- What are the goals of the process? Is the city, town, or county starting from a relatively blank slate as it seeks to understand the full scope of its housing needs, or is it focused on specific policy ideas?

- What is the timeline and decision-making structure that will dictate the process?

Develop an understanding of the community landscape

Staff designing the process should map out who the locality needs to reach and hear, keeping in mind that the “usual suspects” who have a presence in local decision-making often do not represent the views and feelings of the entire community. Intentional efforts should be made to identify the community groups excluded from or underrepresented in decision-making processes in the past. Some guiding questions that can help local leaders ensure that their outreach efforts reach a representative group of constituents include:

- Who is most affected by the housing, land use, and other issues at stake? Consider specific neighborhoods and how these issues affect different racial, ethnic, income, and religious groups, among others. Learn more about neighborhood disparities.

- Which community organizations -such as community organizing groups, service providers, faith institutions, or others- are trusted by local residents and can effectively engage the community members who are most affected?

- Who are the other stakeholders, including housing and non-housing practitioners, industry representatives, advocates, and other governmental agencies, that bring valuable perspectives, concerns, and expertise to the housing planning process?

Identify core questions and trade-offs

While it might seem daunting to present contentious questions to the community, these issues are likely to emerge regardless. It is best to facilitate frank, productive conversations about these concerns from the start in order to ensure an inclusive process and secure community buy-in during the implementation of new policies and programs. The following questions can help identify starting points for these complex discussions:

- What are the most important questions and trade-offs the city must consider?

- Are there segments of the community that will be particularly impacted by the potential outcomes raised by those questions?

Assess government capacity

In order to advance more effective community engagement strategies, localities must assess their capacity to meaningfully carry out these efforts. If necessary, localities may look to retain consultants and partner with community groups to ensure that they have the right skills and expertise. The following questions can help leaders identify what type of engagement government staff are ready to undertake, as well as what work would benefit from external partnerships:

- Does the staff have the appropriate training and skills to engage a diverse group of community members in the decision-making process?

- Does the staff need training on racial disparities, equitable practices, and other topics to help them understand what they are hearing from community groups and respond?

- Does the staff represent and/or have a history of working with the community groups that need to be included?

- Could the city use a consultant with a proven track record of working successfully with a diverse set of stakeholders to help design or facilitate the process?

- Can community-based organizations help build bridges to differentiate community groups?

- In smaller localities: is there sufficient staff capacity to support meaningful participation in an engagement process, and can staff work collaboratively with a consulting team to create meaningful experience during planning?

Assess community capacity

To ensure targeted and robust feedback from community members, localities may also need to provide additional information related to the overall engagement process and the components of a housing strategy. Questions like the ones below can help local leaders ensure that community members have access to the information they need in order to make informed decisions:

- What kind of trainings or materials will community members need to comfortably and meaningfully engage in the decision-making process?

- How will the materials and information be delivered in a way that ensures accessibility for a diverse range of community groups?

Design engagement strategies and identify resource needs

There are a range of engagement strategies to consider based on several factors, including a locality’s scope of planning, the characteristics of the community, the capacities of both the government and the community, the specific questions that need to be addressed, and the resources that are available. Considering the following can inform the development of an engagement strategy that addresses unique local contexts:

- Have some strategies worked better than others in the community in the past?

- Based on the community assessment provided, what other community perspectives should be incorporated through broader outreach? Also, what are the most effective strategies for community-based meetings and outreach to engage those perspectives? Where and when should meetings occur to ensure a diverse range of community members can attend?

- What resources are needed to implement the most effective engagement strategies?

Decide how input will be used

To build community support, it is important to clearly communicate with participants about how the locality plans to use their feedback. This includes input from task forces, public meetings, online surveys, and any other engagement methods. It’s also crucial to follow through on the commitments made regarding this feedback. Ensuring that answers to questions like the following are shared with the public can set the stage for a transparent engagement process:

- How will community input inform the final decision?

- Who will participate in deciding what will be included in the final strategy, and what role did they play in the overall engagement process?

- How will government officials share and discuss with the public which community recommendations were used and which were not, and what were the reasons for those decisions?

Inform the public about next steps through implementation

With support built for the strategy and a strengthened capacity to engage, the community can help see the plan through to successful implementation. The following questions can help leaders identify the types of information most helpful to communicate with the public to build and maintain buy-in:

- What barriers to implementation are likely to arise and what will the staff do to address them? Are these barriers different for different community groups?

- How can the community support the implementation of the housing strategy?

- How can community members engage with implementation and provide feedback during this step?

What engagement strategies have other cities successfully employed?

Many cities use a mix of engagement tools and techniques to ensure they gather robust, representative information from community members. Below, we feature snapshots of different city efforts and detailed guidance on how to pursue four common methods of engagement. Click on the arrows to navigate through the media carousel.

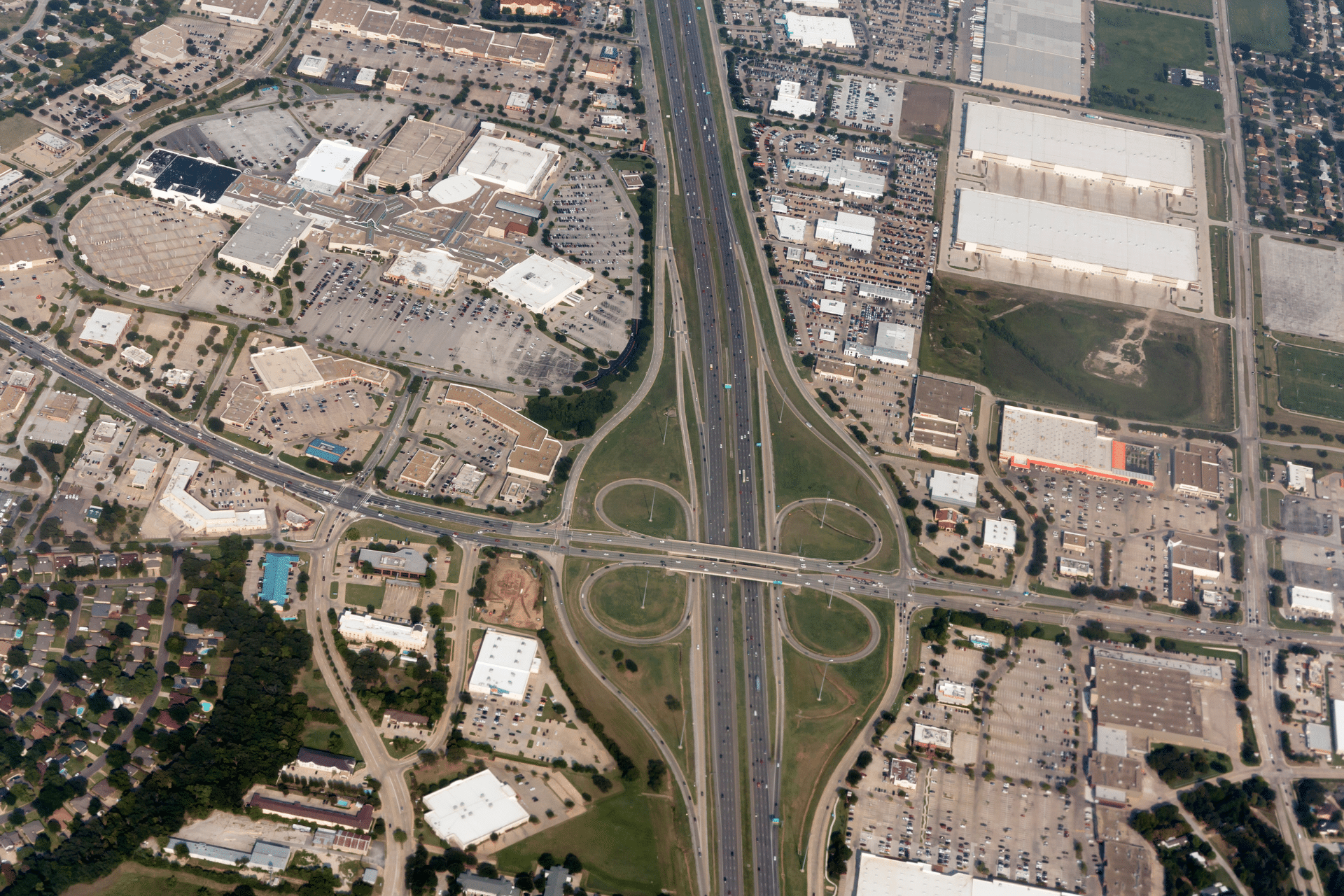

Arlington, Texas

Arlington City Council established a time-limited task force to generate recommendations for a local racial equity plan. The task force included 15 city staff and 15 residents appointed by the mayor and city council. The task force facilitated public dialogue on racial equity through town halls, public meetings, focus groups, and individual interviews.

Twin Cities, Minnesota

An advisory committee supported a regional fair housing analysis by providing feedback on the selection of the consultant, the scope of the analysis, and strategies to overcome barriers to fair housing choice. The committee included 23 members: five were local government officials, while the rest were representatives from various community organizations.

Charlottesville, Virginia

The Advisory Committee for Kindlewood, a federally subsidized housing development, consists of nine resident-elected representatives and three to six members from the broader Charlottesville community (including city staff). The committee is included in every major decision about the community, including choices about the development process, open space, and building scale.

Phoenix, Arizona

City staff bring desired services, such as pet clinics or self-defense classes, to community members. The city presents community members with policy updates and opportunities to provide comments at these locations. These mutually beneficial interactions can form the basis of a consistent and reliable relationship between community members and the city.

Seattle, Washington

The City’s Department of Neighborhoods distributed flyers to 90,000 households; organized 198 meetups in people’s homes, bars, and community centers; conducted door-to-door canvassing; and provided opportunities to talk to city staff at farmers’ markets and community spaces. The input gathered from this process informed eight principles for how the city’s new Mandatory Housing Affordability policy should be applied throughout the city and supported the city’s environmental review of the proposed policy.

Twin Cities, Minnesota

A regional fair housing consortium awarded 17 community organizations a total of $71,000 to collect feedback from the populations they serve. The organizations conducted outreach using a standardized survey. While some organizations found this approach helpful, others felt it had limitations. The insights gained through these microgrants were published in the final fair housing analysis and informed the report’s recommendations.

Elk Grove, California

The city uses Balancing Act, a tool for participatory budgeting, to help residents provide constructive feedback on rezoning decisions. To submit input, residents had to create their own rezoning plans that met the state mandate for housing growth. After residents submitted their plans, city officials reviewed and summarized the results so the City Council could make an informed decision about which sites to rezone for more housing.

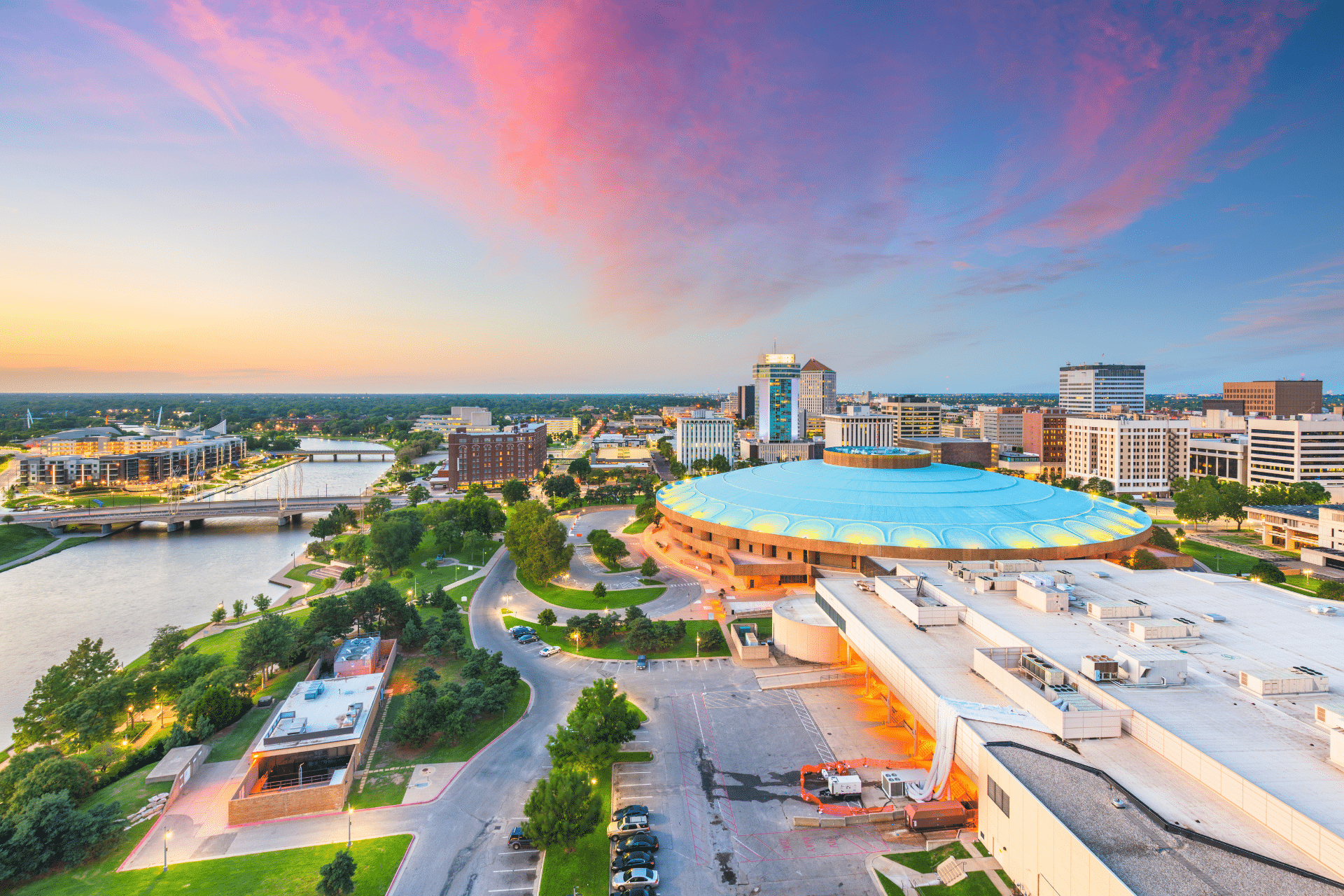

Wichita, Kansas

Wichita complements its in-person engagement efforts with Forum, a website where residents can learn and provide feedback about an array of city issues and projects that range from parcel-specific proposals to the citywide budget. The city dedicated $5 million from the American Rescue Plan Act to use Forum to learn about community affordable housing priorities and disseminate program progress.

Implementing common engagement strategies

There are numerous ways cities can structure engagement initiatives. Below, we detail the purpose and implementation of four strategies to provide cities with common models that can adapt to their local contexts.

Community stakeholder task force

Rationale: An advisory committee or task force can facilitate discussion among a representative set of community advocates, government staff, and non-profit service providers toward a shared analysis of local problems and guidance for policy-making processes.

Responsibilities: In some places, a task force of community representatives and other stakeholders is used to oversee the entire process, including developing broader engagement strategies and drafting the housing plan. In other places, the task force’s role is to vet specific policy questions. Depending on the purpose, the task force might work in smaller subcommittees on particular issues and then reconvene and share their findings with the entire group. It is important to communicate clearly with task force members regarding their responsibilities, the intended use of their recommendations, and the timeline for their work.

Membership: The process of selecting who sits on a community stakeholder task force should achieve a balance between maintaining a manageable size and ensuring representation. This means prioritizing the involvement of the most affected communities, promoting being inclusive, valuing community perspectives, and addressing power dynamics. In many places, a task force typically consists of 20 or fewer individuals, including elected officials and agency staff with diverse perspectives, housing practitioners, industry stakeholders, and representatives from non-housing sectors such as education, environment, and transportation, along with advocates and community representatives. Conducting a landscape review of those most affected by specific housing strategies, community groups, and other stakeholders can help identify the voices that should be at the task force table.

Compensation: Offering stakeholders financial compensation for participating in community boards, commissions, and other long-term participatory bodies is an uncommon practice. However, some localities view it as a promising means of encouraging participatory policymaking, particularly among underrepresented residents. A white paper on the best practices for nonprofits that provide resident honoraria found that incentives that are high enough to cover lost wages and travel time are effective at encouraging involvement.

Facilitation: Successful task forces are often facilitated by neutral and trusted intermediaries. Strategies like collectively developing ground rules, using conflict productively to find collaborative solutions, setting up consistent meeting spaces and time to create a comfortable and predictable environment, and correcting imbalances in communication can make task forces effective.

Resources: Ensuring that task force discussions and decisions are informed by data-driven analyses of market conditions, housing needs, and gaps can help ground group discussion in a common analysis of local challenges and needs. In many places, local governments or philanthropies also invest in trainings on technical housing issues and social justice to help task force members engage in a more informed manner.

Multi-channel community outreach and meetings

Rationale: Combining and adjusting common outreach strategies can help better reach community members by catering to different types of schedules and life circumstances.

Examples:

- Neighborhood-based outreach, such as dispersed community meetings, with a particular focus on reaching those who have historically been excluded from local policy decisions;

- Materials and presentations in accessible, non-technical language with translations available in other languages as needed;

- A clear summary of any relevant data and policy evaluations to encourage engagement rooted in a shared analysis of problems and possible solutions;

- Forums for dialogue on important issues among community members, as well as between community members and officials;

- Efforts to overcome barriers to engagement through translation, childcare, food, and transportation; and

- A clear explanation of how input will be used in the decision-making process and how the community can continue to engage through implementation.

Partnering with and funding trusted community-based groups

Rationale: Community groups can help strengthen engagement by ensuring community members show up to outreach events. Partnering with community groups that have meaningful connections with residents who are typically underrepresented in city outreach efforts is particularly helpful in this regard.

Selection: Successful outreach processes often depend on public officials or the task force overseeing them to have a deep understanding of the community. It’s important for them to know which groups are trusted locally and have a track record of reliability. Cultures, language needs, and levels of trust can differ across communities and are best served by organizations that are rooted in those communities.

Additional resources: Community-based organizations are often resource-strapped, and undertaking new forms of engagement can add a significant amount of work to their existing obligations. Localities can help make outreach by community groups more impactful by providing financial assistance, access to meeting spaces, drafts of outreach materials, and other resources. With this support in place, community groups can reach more neighborhoods, ensure consistent representation, inform residents before meetings, and sustain engagement through project implementation.

Web-based tools

Rationale: Web-based tools can be a helpful supplemental strategy to share information with communities and gather their feedback. These tools can help reach people who do not have time to attend in-person meetings. At the same time, solely relying on web-based tools may disproportionately exclude seniors and people in areas with limited internet access, reducing their opportunity to engage.

Selection: Web-based tools include surveys, online forums, and other dialogue tools. Several companies provide direct-to-government support in creating these online tools; localities may consider the price, amount of customization offered, data privacy methods, and alignment with current data-storage systems as they select among these vendors.

While more rigorous evidence is needed to definitively identify which strategies are most effective, cities across the U.S. are experimenting with a range of promising approaches. For a detailed discussion of how these strategies can help address common barriers to equitable engagement and for more city engagement examples, see Part 2 of our community engagement brief.

How can cities adapt strategies to fit their needs and resources?

The Housing Solutions Lab partnered with Hester Street, an urban planning non-profit that facilitates community-led change, to provide technical assistance to three of our 2023 Peer Cities. The work produced the following materials, which can guide the creation of a new engagement strategy based on a city’s current needs and resources:

- Assess the current state of engagement in your community:

- List stakeholders and organize them according to the level of engagement needed. View the printable template here.

- Identify gaps and opportunities for engagement by power-mapping stakeholders. View the printable template here.

- Strategically plan engagement by working backward, or backcasting, from a long-term engagement goal to near-term activities and actions. View the printable template here.

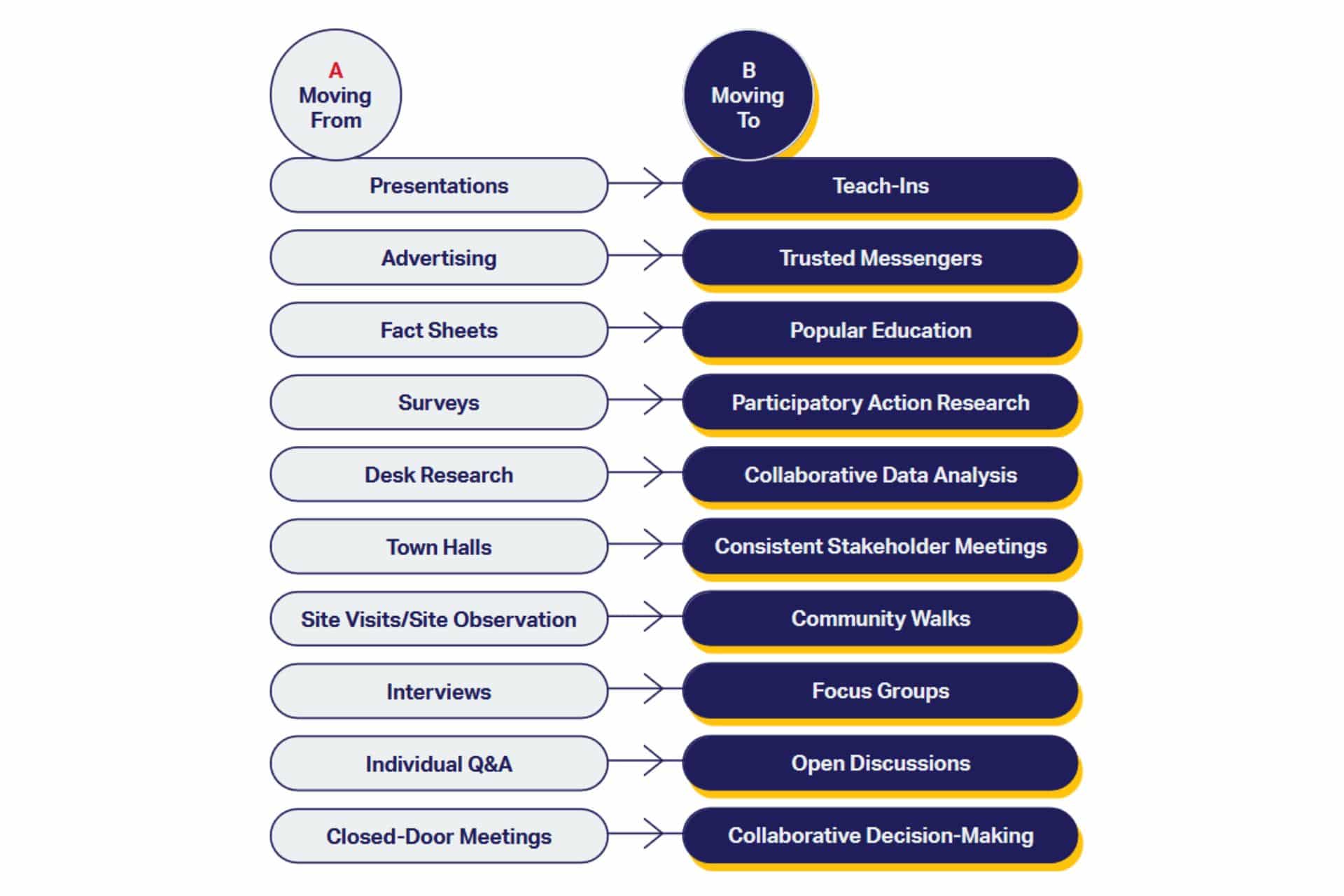

2. Use the information gained from an assessment of your city’s current engagement environment to gradually transform current engagement practices into more meaningful venues for discussion and feedback.

Methods to Shift Engagement Strategies

Source: Hester Street

For more information on the work Hester Street supported, see the final community engagement reports for Skokie, IL; Jackson, TN; and Cheyenne, WY.

How can a city, town, or county measure the success of its community engagement process?

The following questions can help cities gauge the effectiveness of their community engagement:

- Did city officials learn new information about the needs or priorities of the community, particularly from segments that have historically been excluded from or marginalized in government decision-making?

- Did community participants learn about the constraints city officials face, such as limited resources or legal barriers, the unintended consequences of certain policies, or conflicting community needs?

- Did the organizations/participants and the officials involved shift their positions during the process by engaging in dialogue, listening to one another, and learning from each other?

- Are there concrete ways that the community input influenced the final strategy?

- Did the city explain why some community recommendations/requests were not included?

- Did participants, especially those from low-income communities of color and other vulnerable or disinvested communities, build political power and gain more access to government decision-makers that they can use to influence future processes or decisions?