The West End CBA supports youth programs, community-building initiatives, entrepreneurship training, affordable housing development, and additional neighborhood programming. This case study describes the components of a CBA, discusses the principles of effective CBAs, and provides a detailed analysis of the West End CBA.

Key takeaways

- CBAs can help ensure new developments benefit their neighborhood and its residents. The West End CBA was meant to ensure the development of the FCC’s new soccer stadium had positive and equitable outcomes for the historically Black West End neighborhood.

- CBAs can impose a broad range of obligations. The West End CBA includes various commitments for the FCC, including providing financial support for community programming and engagement and offering support for affordable housing development.

- CBAs benefit from community involvement and oversight. The West End CBA’s negotiating parties intended for neighborhood residents and stakeholders to remain involved throughout the CBA’s implementation and the stadium’s development. Over time, the deterioration of this community oversight may have contributed to the CBA’s implementation falling short of some of its goals.

- CBAs can take time to negotiate. The West End CBA has been amended twice. A criticism of the agreement is that the negotiation process was rushed.

About CBAs

A CBA is a legally binding contract, typically between a developer and a community group, requiring the developer to provide certain benefits, such as community programming, housing, employment opportunities, or amenities, in return for the community’s support of a project. CBAs can help ensure that a new project benefits its surrounding community and can include requirements to help prevent the displacement of existing residents and businesses the project might trigger. CBAs can also benefit developers by securing public financing for their projects and mitigating project delays due to community opposition.

CBAs can be created between developers and local governments, community-based organizations, coalitions, funders, and other parties. Typically, a coalition of credible community representatives negotiates CBAs. A community-driven CBA process can help prevent the misuse of CBAs, such as including requirements that are unenforceable or were not discussed with the community. The Partnership for Working Families and the Community Benefits Law Center developed a set of principles that guide an effective CBA and serve as a framework for evaluating whether the agreements used processes that meaningfully include community members and lead to benefits that meet their needs. The Center’s principles are:

- The CBA is negotiated by a coalition that effectively represents the interests of the impacted community (Representative);

- The CBA process is transparent, inclusive, and accessible to the community (Transparent/Inclusive/Accessible);

- The terms provide specific, concrete, meaningful benefits and deliver what the community needs (Specific Benefits); and

- There are clearly defined, formal means by which the community can hold the developer (and other parties) accountable to their obligations (Accountability).

Strong CBAs represent the community’s interests, incorporate measurable requirements, establish a timeframe for implementation, require public-facing reporting, clearly define parties’ responsibilities, and include an enforcement plan. Local government can demonstrate “inclusive leadership” by remaining transparent throughout the CBA process and by establishing an Advisory Committee of residents and local stakeholders which prohibits the developer from trying to control CBA negotiations. Weak CBAs often lack community participation, involve backroom negotiations, are vague, and do not include a strategy for enforcement. Developers may co-opt weak CBAs and use them for their own benefit. Weak CBAs may also mislead communities into believing they will receive specific benefits. Due to poor drafting or a lack of enforcement mechanisms, these agreements may not lead to any actual community benefits that address local needs.

Development of the Cincinnati CBA

In December 2018, the FCC started building a new MLS stadium for 26,000 people on 12 acres in Cincinnati’s West End neighborhood. The project broke ground after Cincinnati’s City Council approved a CBA between the FCC, The Port, and the WECC, and the FCC established the FCC Foundation to serve the stadium’s surrounding community. The City of Cincinnati and The Port provided financing for the development, contingent on the creation of the CBA. The FCC chose the West End for its project because the neighborhood is in an Opportunity Zone, meaning the FCC receives tax incentives for locating its stadium there.

The West End is a predominantly Black neighborhood that has been adversely impacted by urban development projects and population loss. Due to redlining in the 1930s, the neighborhood was one of the few places Black families could live in the city. In the 1950s and 1960s, the construction of Interstate 75 demolished over 1,000 buildings and displaced between 20,000 and 30,000 residents. The West End suffered decades of disinvestment until it recently began receiving renewed attention following the gentrification of an adjacent neighborhood. The West End CBA was designed to prevent the displacement of West End residents while offering additional community benefits.

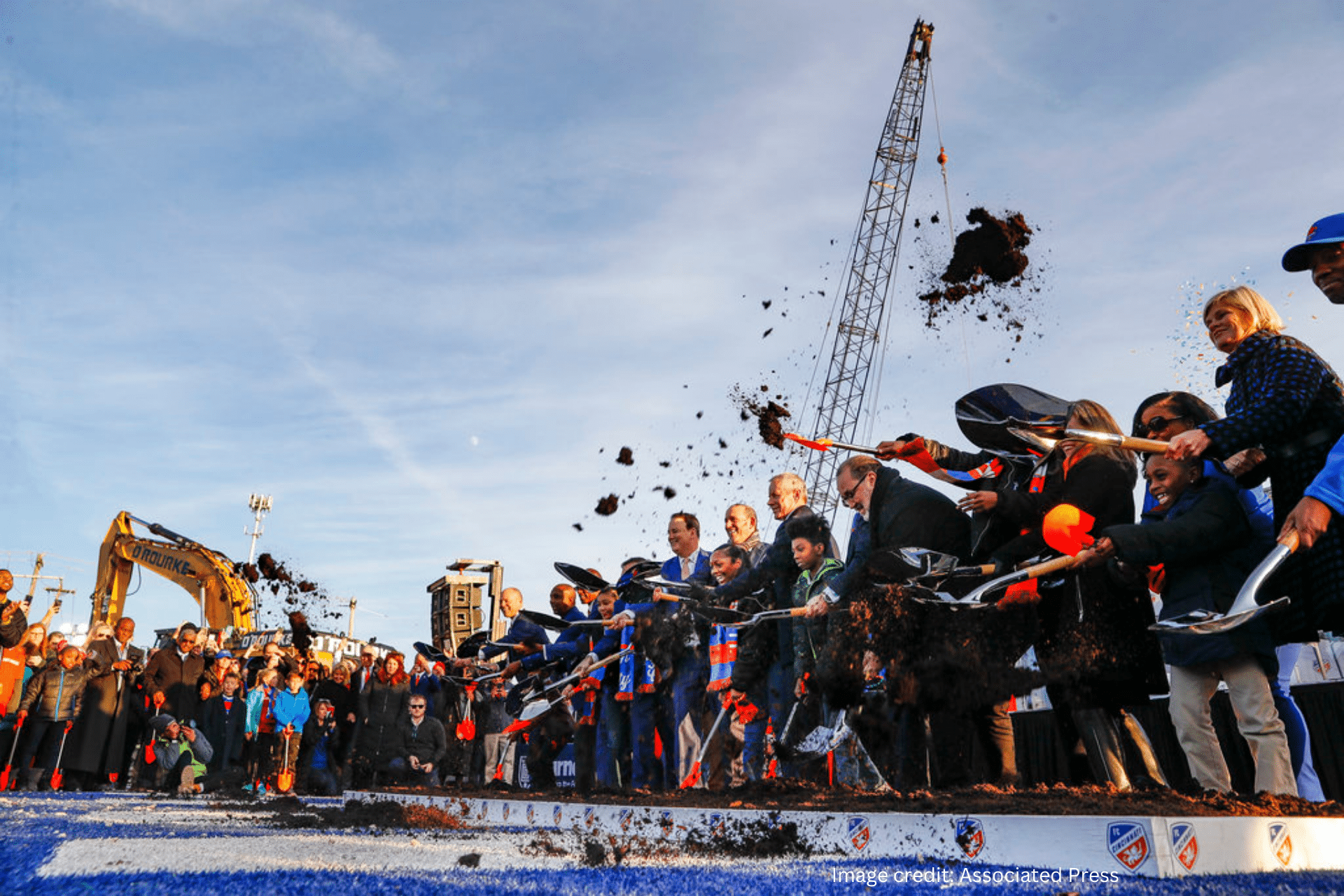

Project leaders, local politicians, and members of the West End Community participate in a formal groundbreaking ceremony on a new stadium for the new Major League Soccer expansion team FC Cincinnati, Tuesday, Dec. 18, 2018, in the West End neighborhood of Cincinnati. Image credit: Associated Press

Negotiating parties

Cincinnati City Council member David Mann was the first to propose a CBA for the MLS stadium. The CBA process included three negotiating parties with signatory authority: FCC, The Port of Greater Cincinnati Development Authority (The Port), and the West End Community Council (WECC), a nonprofit helping guide development in the city’s West End. The CBA process also included active involvement from the mayor, the City Council, and the administration, but these parties were not signatories for the agreement.

Timeline

- 2017: FCC announces its intention to build a new stadium to strengthen its bid to join the MLS.

- April 2018: City Council approves CBA.

- May 2018: City Council approves the first CBA amendment.

- May 2018: FCC is invited to join the MLS.

- September 2018: City Council approves the second CBA amendment.

- December 2018: Establishment of the FCC Foundation; stadium project breaks ground.

- August 2019: Completion of the West End Housing Study.

- December 2019: FCC Foundation announces the first round of 18 grants for community-based organizations totaling $100,000 and provides $100,000 in emergency housing assistance to address the immediate needs of West End residents.

- Spring 2021: Grand opening of the stadium.

Process and terms of the CBA

In an interview with Local Housing Solutions, Ioanna Paraskevopoulos, Former Chief of Staff for City Council member Mann, reported that the FCC, WECC, and other council members initially hesitated to agree to a CBA process because none were sure what a CBA was and what it could accomplish. Council members were also skeptical of how a CBA would be perceived by community members. Paraskevopoulos reported that the City Council recruited experts from Policy Link to educate residents, the FCC, council staff, and key administration officials on CBAs.

Eventually, the city required the FCC to negotiate its obligations with the WECC in the form of a CBA. The following are some significant agreed-upon requirements for the FCC:

- Community engagement. A 17-member community coalition comprised of West End residents and local organizations must oversee the CBA’s implementation, and a Community Design Committee consisting of nine West End residents and interested parties must be established to provide feedback on the stadium’s design.

- Economic inclusion. The FCC must make a good faith effort to meet economic inclusion requirements for contractors and requirements for local hiring, wages, and job fairs targeting neighborhood residents.

- Financial support. Through the FCC Community Fund, the FCC is supporting the West End with more than $6 million over 30 years, including $100,000 in annual grants for community-based organizations and additional funding for a West End Youth Soccer Program, West End community-building initiatives, entrepreneurship training for West End residents, a one-time payment for a housing study, and a one-time payment for a community engagement consultant.

- Housing. The FCC must make annual contributions of an unspecified amount to The Port’s equitable housing development in the West End and other community-based organizations’ housing advocacy efforts. Through the CBA, the FCC also assigned its option to purchase 67 vacant parcels owned by the Cincinnati Metropolitan Housing Authority to The Port.

- Safety. The FCC must commission a traffic study and meet security, beautification, and parking requirements.

The CBA has been amended twice since its first approval in April 2018 because community groups argued the initial versions were inadequate. One notable change was that the original CBA was only between the FCC and The Port, not the WECC, which limited the community’s ability to enforce the CBA. The most recent version of the CBA includes the WECC as a party and additional requirements for the FCC, such as mandating that West End residents and stakeholders help guide how the FCC Community Fund is used. The CBA required a community coalition to be formed to provide oversight of the CBA’s implementation. It also obligated the FCC to provide reasonable support for various community-based organizations’ programs, as well as economic development, arts, and cultural heritage projects in the West End. Alexis Kidd, Community Development Corporation advocate for the Seven Hills Neighborhood Houses, reported that the amended CBA supported the community better than the initial CBA. However, Kidd said that the amended CBA still had “no teeth” for the community to hold developers accountable for fulfilling the terms of the CBA.

Despite criticism from some that the CBA was rushed, Paraskevopoulos said the process helped educate Cincinnati residents on CBAs. Prior to a formal negotiation session, the WECC and representatives from the FCC held several meetings. The CBA likely would have been stronger given more negotiating time; however, the FCC pressured the city to move quickly to ensure their team could be in the MLS. The negotiation process was complicated due to the WECC’s struggle to find a lawyer in the short timeframe allotted for negotiation. Ultimately, Council member David Mann’s office recommended an attorney for the WECC, and the WECC and FCC participated in a day-long negotiation, which resulted in the two parties creating a “term sheet.” The City Council voted to approve the term sheet, which was later formalized and expanded into a full draft of the CBA.

Anne Sesler, FCC’s media liaison, reported that FCC, The Port, and the WECC worked in good faith to develop the CBA and that no one was “left out or underrepresented” because the WECC represents all residents in the neighborhood. Kidd, however, said West End residents were divided in their support for the CBA, and those who opposed the development were not fully represented throughout the process. She attributed this in part to the speed at which the CBA was negotiated, saying the community felt pressed for time and “couldn’t succeed under that timeline.” She also noted that support for the CBA tended to be concentrated among the more affluent West End residents.

Outcomes

In the FCC Foundation’s first year, it reported investing $1 million in the Greater Cincinnati area, primarily in youth sports programming. It also funded the West End Housing Study as required by the CBA. According to the CBA, the Housing Study was intended to analyze the effects of the new stadium and other developments in the West End, recommend measures to encourage investment, and determine strategies to prevent displacement. It supplemented the area’s 2016 West End Speaks plan, which the neighborhood started updating in 2021.

The West End Housing Study included an existing conditions analysis, a review of existing plans and projects, community engagement, zoning analysis, and a location suitability analysis to provide information on the West End’s housing stock. It also included a displacement risk analysis that found many West End residents are at risk of displacement due to expiring subsidies for rental units. The final report provided seven recommendations for the neighborhood:

- Recognize Seven Hills Neighborhood Houses as the lead community development corporation (CDC) in the West End.

- Protect low-income residents from displacement by directing them to resources and increasing their access to opportunities.

- Stabilize the community by preserving existing housing stock.

- Encourage investment in identified areas of opportunities.

- Encourage economic mobility strategies that advance local job creation, business retention and attraction, and celebration of cultural and historical assets.

- Develop innovative partnerships for capacity building and long-term financing.

- Create the West End Annual Housing Report Card for tracking progress and accountability.

In addition to the housing study, the West End CBA required the FCC to reasonably support neighborhood housing efforts and assign its option to purchase vacant parcels to The Port. As of 2021, the FCC had donated $100,000 in emergency housing assistance funds for the West End residents and $200,000 to The Port for affordable housing development in the West End. The Port also identified the West End as a neighborhood that will receive development support.

Paraskevopoulos reported that although the FCC said their project would not displace residents, rental housing around the stadium is increasingly receiving purchase offers from developers, including the FCC. In some cases, the switch to a new property owner has resulted in the displacement of people with low incomes, forcing them to search for another building that accepts Section 8 housing vouchers. Kidd estimated that thousands of residents may have been displaced. Furthermore, a local church and other local businesses were lost as other developers bought land surrounding the stadium development.

Each year, beginning in 2019, the FCC Foundation has released a report sharing updates on their work related to the CBA (A list of annual community reports is included here.) The report, however, is not benchmarked against the terms of the CBA, so the public cannot easily determine whether the CBA’s outcomes are being achieved. In 2022, the FCC Foundation’s efforts to support the West End neighborhood included investing in youth soccer programs, hosting community events, and providing the fourth annual installment of $100,000 in grant funding for West End nonprofits.

Sesler reported that representatives from the FCC, The Port, and the WECC did create a community coalition to oversee the CBA’s implementation as was required in the CBA. The community coalition facilitated community meetings to monitor the CBA’s implementation. Kidd reported, however, that the coalition did not operate as intended. Over time, participation in the coalition became less representative as community members stopped attending meetings. Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, meetings moved online, which further decreased attendance– especially for residents without reliable access to devices and internet connectivity.

Policy implications

The West End CBA demonstrates how localities can use CBAs to navigate situations where the interests of developers and residents conflict, and it demonstrates the types of benefits a CBA can secure. However, the West End CBA is also an example of how challenges during the negotiation process and oversights in drafting can hurt a CBA’s efficacy. Although the West End CBA successfully secured tangible benefits such as funding for affordable housing, its failure to completely prevent residents’ displacement may be a result of rushed negotiations leading to weak representation for residents and a lack of enforcement mechanisms in the final CBA.

Based on the West End example, other localities considering CBAs may want to consider several approaches to ensure their CBA has the capacity to support their communities. Key steps may include: providing upfront education on CBAs to city leadership and the public, and reviewing existing CBAs for similar projects; ensuring the group(s) negotiating the agreement are representative of the community’s residents; allowing sufficient time for negotiations; establishing clear roles and responsibilities in the CBA, including a strong role for legal counsel to ensure the agreement is enforceable; establishing a committee of neighborhood residents and stakeholders to provide oversight of the CBA’s implementation; and requiring public-facing tracking of the CBA’s outcomes to remain transparent about its impacts.

Lessons learned from the West End CBA and other research have also helped inform a CBA Toolkit, a tool that discusses steps to develop a successful CBA.

Annotated resources

- FCC. Information about the FCC, including ticket information, schedule, stats, news, and more.

- The Port. Information about The Port of Greater Cincinnati Development Authority, including the team, current projects, and news.

- WECC. Directory of community councils in Cincinnati.

- FCC’s 30-Year Community Benefits Agreement (Original – April 2023). The first version of the Community Benefits Agreement.

- FCC’s 30-Year Community Benefits Agreement (First Amendment – May 2023). The first amended version of the Community Benefits Agreement.

- FCC’s 30-Year Community Benefits Agreement (Second Amendment – September 2023). The second amended version of the Community Benefits Agreement.

- FCC Foundation. A website with more information on the Foundation’s programs, initiatives, and events as well as annual community impact reports.

- Community Benefits Agreement. Resources on CBAs from Policy Link’s All-In Cities Policy Toolkit.

- Community Benefits Agreements Database. A collection of publicly available CBAs assembled by the Sabin Center at the Columbia Law School.

- Guide to Advancing Opportunities for Community Benefits Through Energy Project Development. A guide on community benefits agreements from the U.S. Department of Energy.

- Community Benefits Agreements: Making Development Projects Accountable. A report from Good Jobs First on community benefits agreements and the requirements they can include.

- Community Benefits 101. A brief presentation from Reimagine Appalachia discussing community benefits agreement basics.

- CBA Toolkit. A toolkit from Action Tank that discusses CBAs, building a coalition, identifying community priorities, approaching a developer, negotiating, and more.

Acknowledgments

This case study was informed by interviews with Ioanna Paraskevopoulos, Former Chief of Staff for Cincinnati City Council member David Mann; Alexis Kidd, Community Development Corporation advocate for the Seven Hills Neighborhood Houses; Laura Brunner, President & CEO of The Port; and Anne Sesler, FCC’s media liaison.