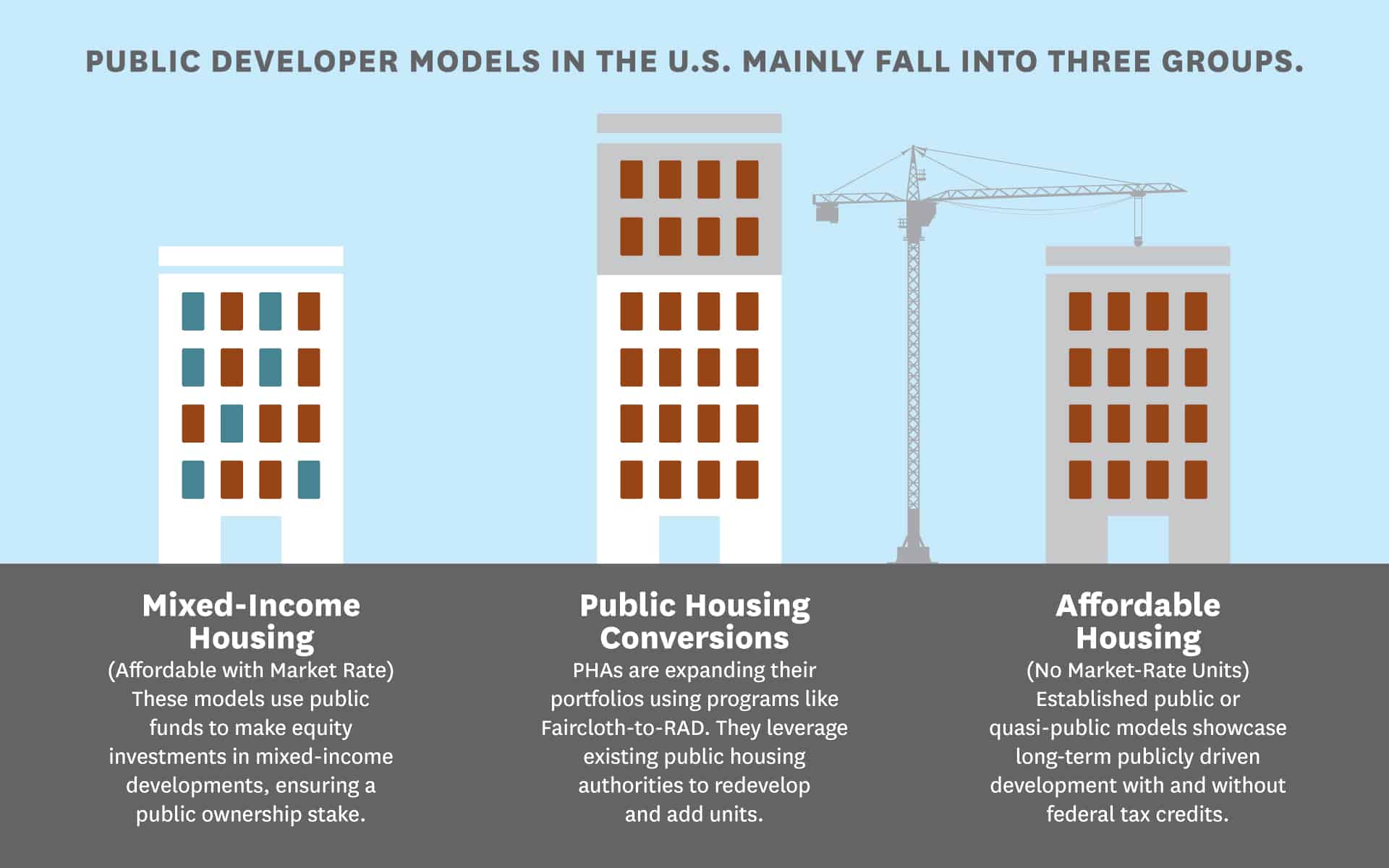

The term “social housing” can mean many things to many people. Here, we focus on models of public development and ownership, which include scenarios where local or state entities serve as a real estate developer, invest significant financial resources in exchange for an active role in decision-making, or act as long-term owners of the housing or land it’s built on. Such public developer models exist across the globe, in cities like Singapore, Helsinki, and Vienna.

To better understand different approaches, the NYU Furman Center and Housing Solutions Lab scanned models of public development and ownership in the U.S. and abroad.

Drawing on interviews with stakeholders and experts, programmatic documents, and underwriting materials, the Furman Center and Lab developed a typology of public developer models. We also studied the contextual factors that shape these models, and the financing and regulatory tools they employ to make public development of housing feasible.

In the U.S., public housing is the most familiar version of public development.

However, the last century has seen a gradual shift toward relying on for- and non-profit developers to provide affordable housing in exchange for a variety of subsidies.

History of U.S. public housing development

Public housing construction begins in the U.S. under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal

1934Public housing agencies use federal loans to construct hundreds of thousands of new units

1940s-1950sUrban renewal policies demolish many low-income neighborhoods and replace them with public housing projects

1950s-1960sThe U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is created to oversee the public housing program

1965President Richard Nixon imposes a moratorium on new federal housing subsidies

1973Congress creates the Section 8 program, representing a shift away from public housing in favor of housing vouchers

1974HUD and the public housing program see drastic budget cuts under President Ronald Reagan

1980sCongress establishes the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) to incentivize private developers to build affordable housing

1986The Faircloth Amendment caps the number of public housing units at the number that existed on October 1, 1999

1999After nearly 50 years of disinvestment, some public housing authorities and other local and state agencies have begun to innovate new models of public development.

U.S. localities move toward new models of public development

Montgomery County creates its Housing Production Fund (HPF) to develop large-scale, publicly-owned mixed-income housing

2021The Faircloth-to-RAD program enables PHAs to build new affordable units, with Boston and Cambridge as early adopters

2021Atlanta incorporates the Atlanta Urban Development Corporation (AUD) to engage in public mixed-income development

2023Chicago passes the Green Social Housing Revolving Fund to create over 600 rental homes every five years

2024There are a variety of factors driving localities to pursue public development:

- They don’t have a strong enough sector of for-profit and nonprofit affordable housing developers

- They have a very strong affordable housing development sector, but it has tapped out the available supply of federal tax credits

- PHAs see opportunities to improve their stock and add new units along the way

- Advocates have called for housing that is decommodified

Removed from the speculative market, so that it cannot be bought and sold for a profit or act as a vehicle for investment.

, permanently affordable, and socioeconomically diverse

Learn more about public developer models in the U.S.

Click on the locations below to learn more about each case study.

Mixed-income housing group

Overview

The county’s Housing Production Fund is a revolving loan fundA pool of capital that provides low-cost loans for housing development. Upon repayment, funds are returned to the pool for use in other projects. that makes short-term construction loans for new housing projects developed by the Housing Opportunities Commission, the county’s public housing authority (PHA). These loans take the place of private equity and lower the cost of financing.

- In addition to the revolving fund, the PHA draws on a range of tools, including property tax exemptions, risk-share financing from the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Treasury’s Federal Financing Bank (FFB), self-insurance

A program in which localities create a pool of funds to cover potential losses, rather than purchasing traditional insurance.

, inclusionary zoning, public land strategiesPractices, such as land banking, that leverage vacant, underdeveloped, or otherwise available parcels for new construction.

, and cross-subsidizationA financing structure in which income produced by units priced at the market rate is used to subsidize the costs of affordable homes at either the building or portfolio level.. - The PHA plays a major role in development and has majority ownership of the housing it produces.

- HPF-financed projects are large-scale, mixed-income buildings (with at least 30 percent of units affordable to households with incomes at 50-70 percent of AMI). Two projects comprising more than 730 units are completed or under construction, and more than 2,000 units across four projects are in the pipeline.

Description

Motivation

According to local officials, Montgomery County projected a significant need for additional housing, including affordable housing, but realized that its allocation of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTCs) and Private Activity Bond (PAB) volume cap were already being maximized and would be insufficient to meet that need. The county’s high-capacity PHA also saw an opportunity to enter construction deals that were stalling because of the high cost and uncertainty of private equity, and in doing so, to lower costs and gain an ownership stake that could translate into greater affordability and long-term value for the public.

Governance structure

The Housing Opportunities Commission (HOC) is the PHA of Montgomery County, Maryland. It also acts as a housing finance agency, with the ability to issue taxable bonds rated A2 by Moody’s. The HOC is governed by a volunteer commission appointed by the county executive and approved by the county council. The Commission’s FY24 operating budget of $339 million mainly consists of voucher funding and federal subsidy pass-throughs, while its capital budget of $255 million is funded by bond proceeds and tax credit equity. The HOC has extensive development experience, including development of mixed-income housing. The agency’s real estate division includes about 17 staff members, including project managers, analysts, quality oversight, relocation managers, and construction professionals.

Financing model

In 2021, Montgomery County created a Housing Production Fund (HPF), a revolving loan fund that seeks to provide “low-cost, construction-period financing to HOC’s developments.” HPF loans are designed to replace private equity investments in the construction financing capital stackA capital stack is the structure of the various financing sources used to fund a real estate project, and typically includes a combination of equity and debt. The stack determines who will receive the income and profits generated by the development and in what order.. They have interest rates below 5 percent, which is significantly lower than the 15-20 percent rates of return expected for private equity investors. Because the revolving loan is “taken out” (the principal is repaid) when a project converts to permanent financing, its main function is to help overcome the hurdle of construction.

The HPF was approved by the Montgomery County Council in March 2021, and the council agreed to fund the principal and interest payments of up to $3.4 million annually for a $50 million bond issuance by the HOC. The council then approved a second issuance of an additional $50 million in May 2022 for a total annual appropriation of $100 million in bond revenue. The HOC anticipates that the HPF will cover a total of $250 million in construction loans, funding approximately 3,000 units in a 20-year period. Over this period, the bond issuance will be fully repaid, after which point the county expects the fund to revolve at no additional cost.

Housing projects

Montgomery County’s HPF model is designed to create large-scale, mixed-income housing projects. Up to 70 percent of units in each project have market-rate rents, and at least 30 percent of units have restricted rents. Of the affordable units, at least 20 percent must be affordable to households earning 50 percent or less of the area median income (AMI). At least another 10 percent of units must be affordable to households earning incomes eligible for Montgomery County’s inclusionary zoning program (65-70 percent of AMI). Rent from the market-rate units cross-subsidizes the affordability of the income-restricted units.

The HOC’s first HPF-financed project, The Laureate, has over 250 units and was constructed on the site of a 95-unit public housing development adjacent to the Shady Grove metro station. Additionally, construction is underway on Hillandale Gateway, a more than 400-unit complex of multifamily and senior apartments built to passive house standards and located in Silver Spring. As of fall 2023, an additional four developments ranging from 180 to over 1,000 units were in the HPF pipeline.

Development and ownership structure

In the HPF model, the HOC is both the developer and the majority owner of the housing produced. For instance, the HOC has a 70 percent ownership stake in the Laureate. The HOC typically hires a general contractor for construction, who is paid a “builder’s fee” of 4-4.5 percent of the construction contract for a new HPF-financed building, but the HOC itself collects the developer’s fee.

Montgomery County can be a challenging development environment, and the HOC is sometimes able to enter a project that has stalled to help move it forward. As an example of this model in practice, one of the HOC’s projects was started by a private developer who faced financing issues, which allowed the HOC to enter the deal, infuse the project with affordable units, and also gain control of the development.

Additional tools used

What is unique about Montgomery County’s model for constructing income-restricted housing is its non-reliance on LIHTC. To achieve this, the HOC harnesses a variety of tools in addition to the HPF loans and mixed-income cross-subsidization described above. One of these tools is property tax exemptions. The HOC’s ownership of the completed properties exempts them from property taxes, which lower a property’s operating costs. In addition, if a certain share of units in the property (greater than 25 percent) are deemed affordable, the project qualifies for impact fee reductions and other exemptions from the county.

Another tool lies in the county’s public land strategies. The HOC often leverages publicly-owned land, including aging public housing developments, to lower total development costs (TDC). In the HOC’s experience, using public land lowers the project’s cost by 10-15 percent; a substantial but not tremendous impact.

The HOC’s status as an HFA that is a qualified risk-share lender is extremely useful in this model. Using FHA/FFB risk-share financingA program that enables local housing finance agencies to offer low-interest multifamily housing loans and share the risk of losses with HUD’s Federal Housing Administration (FHA)., the HOC is able to fund projects with a 40-year amortization in term at a low rate of interest. In the case of The Laureate, the financing is structured in such a way that, after construction, the HOC stays in the deal with the addition of a mezzanine lender (possibly a mission-focused private investor). The permanent debt, in the form of a risk-share loan, covers the construction loan and pays off as much of the HPF financing as possible.

Compared to a typical market-rate developer, the HOC can access less expensive construction financing through the HPF, unlock tax abatements, lower the cost of insurance through self-insurance mechanisms, and help guide the project through local approvals, shortening the land entitlement processThe land entitlement process is the legal process by which a landowner obtains government approval to develop a property. Entitlement may include various kinds of permits, rezonings or zoning variances, and utility and road approvals.. Separate from the HPF, the HOC also has two lines of credit with PNC bank in an aggregate amount of $210 million, which allows the HOC to act nimbly as a joint venture developer and/or lender, with more flexibility than comparable entities.

Although the HOC has not executed any Faircloth-to-RADA program that allows PHAs to build new public housing units and immediately convert them to units with project-based Section 8 contracts. In doing so, PHAs must remain within their “Faircloth Limit,” that is, the number of units they owned or operated as of 1999. projects yet, in the future, the HOC’s publicly-developed housing projects could be paired with Faircloth-to-RAD allowances and vouchers. This combination could offer deep operating subsidies for some of the units, allowing the housing of extremely low-income residents while still collecting rents closer to market rates.

Mixed-income housing group

Overview

- Invest Atlanta manages a Housing Production Fund (HPF), which is a revolving loan fundA pool of capital that provides low-cost loans for housing development. Upon repayment, funds are returned to the pool for use in other projects. that provides “mezzanine-level, low-interest construction loans to developments that commit to long-term affordability.” These projects are owned by the Atlanta Urban Development Corporation (AUD) and built in partnership with a private developer identified via a Request for Qualifications (RFQ) process.

- In addition to the revolving loan fund, the city leverages a suite of tools, including property tax exemptions and cross-subsidizationA financing structure in which income produced by units priced at the market rate is used to subsidize the costs of affordable homes at either the building or portfolio level..

- Atlanta’s public land strategies

Practices, such as land banking, that leverage vacant, underdeveloped, or otherwise available parcels for new construction.

are a cornerstone of its approach. - The city has not yet completed any projects via the AUD. All AUD projects will have at least 20 percent of rental units affordable to households earning at or below 50 percent of AMI and 10 percent of rental units targeted to households at or below 80 percent AMI.

Description

Motivation

Atlanta aims to build and preserve 20,000 affordable units by 2026, and low-income housing tax credits will only get them partway to that goal. In order to fill the gap, the city has sought to emulate Montgomery County’s public developer model and maximize the use of its public land through AUD.

Governance structure

The Atlanta Urban Development Corporation (AUD) is an incorporated subsidiary of Atlanta Housing (AH), the housing authority of the City of Atlanta. AH is well represented on the AUD board; four board members are also board members of AH, and three others are recommended by the mayor and approved by AH. As a wholly owned subsidiary of AH, the AUD can issue bonds, own property, and award property tax exemptions just like a public housing authority (PHA). As a start-up entity that does not share AH’s balance sheet, however, the AUD generally relies on a “benefactor” like the city or Invest Atlanta to issue debt on its behalf. The AUD is also responsive to the City of Atlanta and Invest Atlanta, the city’s economic development authority. Besides recommending the three AUD board members, the city supports the AUD with seed funding. The city is currently considering acting as a debt guarantor for AUD projects (the city is AA+ rated). Invest Atlanta’s role includes helping with project intake, underwriting, project approval, and closing, and it may also work with the AUD to develop long-term public financing in the future.

Financing model

Funded by the 2023 Housing Opportunity Bond, a $38 million appropriation by the City of Atlanta, the Housing Production Fund (HPF) is structured to provide “mezzanine-level, low-interest construction loan to developments that commit to long-term affordability through AUD ownership.” The joint effort requires the AUD to identify HPF projects, with Invest Atlanta managing the bond financing and controlling and approving fund drawdowns. The AUD HPF model calls for the loans to cover up to 20 percent of the construction capital stackA capital stack is the structure of the various financing sources used to fund a real estate project, and typically includes a combination of equity and debt. The stack determines who will receive the income and profits generated by the development and in what order. for up to a five-year period, with the below-market loans intended to be taken out at permanent loan conversion. By providing interest-only construction financing at rates lower than the market average and building on publicly-owned land, which reduces overall construction costs and acts as a form of additional equity, the AUD HPF model is designed to lower total development costs in exchange for the creation of affordable units. This approach is similar to the Montgomery County Housing Opportunity Commission’s HPF.

The AUD has released two Requests for Qualifications (RFQs) to date for the redevelopment of Fire Station 15 and Phase I of the redevelopment of Thomasville Heights, a former public housing site. The RFQs note that neither project should make use of Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) funding. Instead, that equity is meant to be replaced by the following combination: no land acquisition, lower-cost equity investment from a government entity, an exemption from property tax payments, and cross-subsidization with market-based rents. To that end, the AUD outlined an example capital stack: 5-10 percent of total development costs (TDC) would be covered by AUD land acting as equity; another 5-10 percent of TDC would be additional equity, either from investors or private sources; up to 20 percent of costs would be covered by lower-cost debt, provided by the HPF as described above at an interest rate of 6 percent or lower; and a market-based construction loan would cover the remaining 60 percent.

Housing projects

The AUD has not yet broken ground or selected developers for its upcoming projects. However, in its RFQs, the AUD noted that at least 20 percent of rental units in AUD projects must be affordable to households earning at or below 50 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI), and 10 percent of rental units must be targeted to households at or below 80 percent AMI. Rent from the market-rate units will cross-subsidize the affordability of the income-restricted units. The Thomasville Heights project is also expected to include homeownership units with similar levels of affordability.

Development and ownership structure

The AUD intends to work with private developers but retain an ownership stake in its projects to ensure long-term affordability. When considering how to allocate equity stakes in a particular project, the AUD will consider the relative risk to itself. For example, the AUD might be more interested in retaining a full equity stake and compensating its development partner with a developer fee in a project providing workforce housing, since there is strong demand for units affordable at 80 percent AMI. In contrast, projects with higher numbers of market-rate units might be riskier because they are more challenging to lease up. However, it is worth noting that units with higher rents also generate higher returns and could help make projects feasible in higher-opportunity markets. In those cases, the AUD might be more interested in granting an equity position to the developer partner to ensure that the entire team has a stake in the successful outcome of the project.

Additional tools used

The AUD and its partners are implementing public land strategies to maximize the value captured from municipal land. According to local officials, Atlanta has traditionally contributed public land to LIHTC deals or sold the land to private developers. While this approach has generally reduced costs, it has not necessarily provided a comparable return in value. In some cases, it has yielded short-term returns without a guarantee of future benefits. Officials believe that combining public land with public funds can not only lower development costs and build more affordable units but also generate long-term returns that can be recycled for public purposes.

As a subsidiary of Atlanta’s housing authority, AUD can also award property tax exemptions, which will lower operating costs for projects. These savings can be passed on to tenants in the form of deeper rent affordability.

Mixed-income housing group

Overview

- Colorado sets aside 0.1 percent of existing state income tax revenue for an Affordable Housing Finance Fund (AHFF) to support affordable housing development across the state.

- Through the AHFF, Colorado leverages cross-subsidizationA financing structure in which income produced by units priced at the market rate is used to subsidize the costs of affordable homes at either the building or portfolio level. and land banking to achieve its development goals.

- The greatest portion of AHFF is allocated to an equity program, through which the state makes equity investments with below-market rates of return for the construction of new mixed-income housing developments. Tenants in state-equity-financed buildings are automatically enrolled in a Tenant Equity Vehicle (TEV), which allows them to share in the profits their buildings generate.

- The equity program prioritizes mixed-income housing and requires projects to be affordable to households with an average income at or below 90 percent of AMI. Colorado announced equity investments for 628 units across six projects this year, a volume that they expect to more than double in future years.

Description

Motivation

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, Colorado has faced a growing housing shortage and a deepening affordability crisis. In 2022, Colorado voters approved Proposition 123 to set aside 0.1 percent of state income tax revenue for housing initiatives, ranging from homelessness prevention to housing development. More than half (60 percent) of Proposition 123 funds are allocated to the Affordable Housing Finance Fund (AHFF).

Governance structure

The AHFF is managed by the Colorado Office of Economic Development and International Trade (OEDIT), with the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority (CHFA) as a third-party contract administrator.

Financing model

The AHFF oversees three primary initiatives: a land banking program, a concessionary debt program, and an equity program. Each program allows for mixed-income housing in which market-rate units may cross-subsidize units with below-market rents. To be eligible for AHFF funding, localities must first commit to increasing their affordable housing stock by 3 percent annually for three years regardless of the program they choose to participate in.

Roughly 15 to 25 percent of the AHFF is allocated to the land banking program, which provides grants and forgivable loans to local governments and eligible nonprofits. Funding must be used for the acquisition or preservation of land for affordable homes, either for sale or rental. The program prioritizes high-density housing and imposes income limits of 60 percent of the area median income (AMI) for rentals and 100 percent of the AMI for homeownership.

Approximately 15 percent to 35 percent of the AHFF is allocated to the concessionary debt program, which provides gap financing for LIHTC projects and other low- and middle-income multifamily rental developments. The average income for tenants in income-restricted units cannot exceed 60 percent of the AMI. Up to 25 percent of the development’s units may be market-rate; however, those units are not eligible for financing via the program. The concessionary debt program also offers debt financing for modular housing, which includes tiny homes, kit homes, and 3D-printed homes.

The remainder and bulk of the AHFF, roughly 40 to 70 percent, is allocated to the equity program. In this program, the state makes equity investments with below-market rates of return for the construction of new mixed-income housing developments. The program prioritizes mixed-income housing and requires projects to be affordable to households averaging at or below 90 percent of the AMI. Tenants in these units will also be enrolled in the Tenant Equity Vehicle (TEV), a program designed to allow renters to tap into the value of their buildings. After living in a state-equity-financed building for at least a year, tenants will begin to access monthly and end-of-year cash payouts in exchange for on-time rent payments. The exact parameters of the TEV are still under development. Funding will initially come from the interest the state collects in its concessionary debt program but may eventually be derived from any profits derived from the sale of equity-financed buildings.

Housing projects

In July 2024, Colorado announced $39.4 million in equity investments for 628 units across six new buildings in the equity program, with individual awards ranging from $2.8 to $15 million. These units will be enrolled in the TEV, and income-restricted units will not exceed an average of 90 percent of the AMI. Program administrators also anticipate that the concessionary debt program will finance approximately 3,000 units through 2024.

Development and ownership structure

The AHFF provides grants, loans, and other types of financing to localities and eligible nonprofits, who serve as developers. Since Colorado law limits how the state interacts with private businesses, equity investments in these properties will yield returns for the state but do not currently translate into an ownership stake. However, this arrangement may evolve in the future.

Additional tools used

The land banking program under the AHFF acquires and preserves land to develop affordable housing. The program also allows mixed-use development, which can generate additional revenue for a project as long as the primary use of the land is for affordable housing.

Mixed-income housing group

Overview

- The City of Chicago’s new Green Social Housing Revolving Fund is modeled after the Housing Production Funds in Montgomery County, Maryland; and Atlanta, Georgia. This revolving loan fundA pool of capital that provides low-cost loans for housing development. Upon repayment, funds are returned to the pool for use in other projects. will provide lower-cost construction loans to developers on the condition they sell the building back to the local government following completion.

- In addition to the revolving loan fund, the city plans to leverage various tools, including property tax abatements, cross-subsidizationA financing structure in which income produced by units priced at the market rate is used to subsidize the costs of affordable homes at either the building or portfolio level., and Faircloth-to-RADA program that allows PHAs to build new public housing units and immediately convert them to units with project-based Section 8 contracts. In doing so, PHAs must remain within their “Faircloth Limit,” that is, the number of units they owned or operated as of 1999..

- The city projects the fund will create over 600 rental homes every five years.

Description

Motivation

Chicago’s Tax Increment Financing (TIF) program has been a critical source of funds for affordable housing across the city. However, the program is beginning to wind down, with nearly 45 TIF districts set to expire by the end of 2027. As TIF becomes a less reliable funding stream and the city exhausts its pandemic-related resources, Chicago has turned to bond financing as a more sustainable alternative. The Green Social Housing Fund is one of several newly approved bond-based initiatives aiming to increase the city’s supply of affordable housing.

Governance structure

As the fund was approved by the Chicago City Council in April 2024, much of its administrative structure remains unclear. However, the city will likely create a separate entity through a program ordinance to run the program. The Chicago Department of Housing will likely be involved and contribute valuable underwriting experience gained from its role in LIHTC deals.

Financing model

The fund will be seeded with $115 to $135 million out of the $1.25 billion bond issuance approved in April 2024. Since the fund revolves, the city anticipates this one-time allocation to fund many projects over time. With this financing structure, such developments are intended to be self-sustaining, with rents covering operating expenses and public ownership ensuring long-term affordability.

Housing projects

Chicago has not yet broken ground on a project or provided loans to developers. However, the city is weighing two options for building out a potential pipeline of projects. The first would be to enter a project that has stalled and offer financing in exchange for a stake in the final project and the inclusion of affordable units. A second option would be to consider sites that will open up during the course of the Red and Purple Modernization, the largest capital project in the Chicago Transit Authority’s history. The higher rents in some of those neighborhoods could be sufficient to cross-subsidize mixed affordable properties and would allow the city to manage projects from the beginning of their development.

Development and ownership structure

According to Chicago’s bond book, the fund will provide low-cost construction loans to developers who will sell the building back to the local government upon completion. Once the city owns the building, it will contract a property manager to operate it and coordinate with a tenant governance body.

Additional tools used

The city is looking into additional means of lowering total development costs and subsidizing affordable units, many of which were also used or explored by Montgomery County and Atlanta. For example, projects financed by the revolving fund would be eligible for a tax abatement under a statewide program. In addition, the Illinois Housing Development Authority may be able to collaborate as a risk-share lender to help lower costs. Finally, Chicago has some of the largest numbers of Faircloth units in the country, and the city is also interested in using the fund to inject additional subsidy to Faircloth-to-RAD projects.

Public housing conversions group

Overview

- The Boston Housing Authority (BHA) is planning to harness the Faircloth-to-RADA program that allows PHAs to build new public housing units and immediately convert them to units with project-based Section 8 contracts. In doing so, PHAs must remain within their “Faircloth Limit,” that is, the number of units they owned or operated as of 1999. program to add thousands of new, affordable units on publicly-owned sites. As a non-Moving to Work agency with high Small Area Fair Market Rents (SAFMRs), the BHA can access relatively high Faircloth-to-RAD subsidies per unit.

- In addition, Boston plans to tap a range of tools, including public land strategies

Practices, such as land banking, that leverage vacant, underdeveloped, or otherwise available parcels for new construction.

, property tax exemptions, and cross-subsidizationA financing structure in which income produced by units priced at the market rate is used to subsidize the costs of affordable homes at either the building or portfolio level.. - BHA intends to convert nearly 3,000 units over the next decade.

Description

Motivation

Boston has lost nearly 3,000 public housing units since 1999. In 2023, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu set out to reverse this trend by directing the Boston Housing Authority to restore 2,891 units, the maximum allowed under the authority’s Faircloth limit. To bridge the financing gap, the city aims to blend the Faircloth-to-RAD program with other tools.

Governance structure

The Boston Housing Authority (BHA) is a public housing authority (PHA) that operates at the municipal level. The agency is managed by an administrator who is appointed by the Mayor of Boston. The mayor also appoints a nine-member Monitoring Committee – of which five members are public housing residents and one is a voucher-holder – to oversee the work of the BHA and report on its activities.

Financing model

The Faircloth-to-RAD program, established in 2021, allows PHAs to build new public housing (Section 9) units and immediately convert them to units with project-based Section 8 contracts. Through the program, PHAs can usually access deeper per-unit subsidies. In BHA’s case, converting Section 9 subsidies to project-based vouchers through Faircloth-to-RAD can increase the level of subsidy to about $1,200 per month per unit. However, this still falls short of what is typically necessary to finance new construction.

Boston’s transformative opportunity stems from the combination of Faircloth-to-RAD with Small Area Fair Market Rents (SAFMRs). SAFMRs allow PHAs to calculate Section 8 subsidy amounts at a neighborhood rather than a metropolitan level. In this way, tenants have access to higher subsidy levels in more expensive neighborhoods. In July 2023, HUD gave non-MTW housing authorities that have implemented SAFMRs the ability to raise Faircloth-to-RAD subsidy levels to the small area payment standard (MTW authorities are not able to do the same). This will give BHA up to $3,200 per unit per month in subsidy in certain neighborhoods, compared to $1,200 under Fair Market Rents. The BHA intends to issue debt on the project-based vouchers it will receive to finance construction, and the increase in federal subsidy per unit will enable the BHA to more than double the debt it can generate, making development much more feasible.

Housing projects

Boston has not yet broken ground on these new projects. As of July 2024, the city is seeking input from both developers and residents on potential sites for public housing units.

However, BHA has considerable experience with mixed-income development, particularly development that includes homes for extremely low-income families (those with incomes at or below 30 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI)). In the past decade, BHA projects have typically included 80 percent of units with market-rate rents and 20 percent targeted towards extremely low-income households using project-based vouchers. Rental income from the market-rate units cross-subsidize the income-restricted units. The agency also finds that there are relatively more resources locally dedicated to providing affordable homes to households with incomes between 60 and 70 percent of the AMI, while there is a scarcity of housing targeting rents affordable to households with incomes between 80 and 100 percent of the area’s AMI. As BHA expands its public development work over the next decade, it aims to evolve its model to support more homes affordable to households with incomes just below 100 percent of the AMI.

Development and ownership structure

BHA manages most new development and redevelopment projects in partnership with private developers who provide expertise or technical capacity. As it embarks on its Faircloth-to-RAD development pipeline, the agency anticipates exploring alternate management models, including possibly bringing all development activities in-house or hiring private developers for turnkey projects. BHA also often relies on partnerships with the City of Boston and MassHousing, the state housing finance agency, to finance and implement its deals. BHA has bonding authority but relies on MassHousing to support financing at the scale of its recent, large developments. Furthermore, many of BHA’s redevelopment efforts have utilized grant funding from the City of Boston or the state budget to support non-construction needs like remediation or tenant relocation.

Additional tools used

Thus far, all of BHA’s development and redevelopment efforts have taken place on land already owned by BHA and, therefore, exempt from property taxes. As the agency creates a plan for developing its 3,000 Faircloth units over the next decade, it has identified 50 publicly owned sites of varying sizes that could support development.

Public housing conversions group

Overview

- The Cambridge Housing Authority (CHA) is combining Faircloth-to-RADA program that allows PHAs to build new public housing units and immediately convert them to units with project-based Section 8 contracts. In doing so, PHAs must remain within their “Faircloth Limit,” that is, the number of units they owned or operated as of 1999. subsidies with federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTCs) to finance public housing redevelopment and add new units. This combination allows the agency to prioritize deeper affordability.

- In addition to these financing tools, CHA has benefited from property tax exemptions.

- CHA has converted 203 units across two projects and has 1,500 more units in the pipeline.

Description

Motivation

The Cambridge Housing Authority (CHA) has over 1,500 units of unbuilt Faircloth authority. However, while some PHAs can combine Faircloth-to-RAD with small area payment standards to access a deeper level of subsidy in high-rent ZIP Codes (see the Boston Housing Authority case study), CHA does not have this ability. As a result, CHA has explored other financing options, including federal tax credits, to help projects “pencil.”

Governance structure

CHA is a federally-funded public housing authority (PHA). It is managed by a five-member board: one resident, three community members appointed by the town manager, and one community member appointed by the governor.

Financing model

Unlike the Boston Housing Authority (BHA), CHA has a Moving-to-Work (MTW) designation from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), giving it greater flexibility to shift funds between programs but excluding it from the special ability to raise Faircloth-to-RAD subsidy levels in line with small area payment standards. Instead, CHA combines Faircloth-to-RAD with LIHTC, soft debt from the state’s HFA, and, in some cases, investments from the City of Cambridge.

Housing projects

A recent CHA redevelopment project has used this financing model and is about to begin construction. The project relies on $10-12 million from LIHTC, approximately $12 million in soft debt from the state, debt on Faircloth-to-RAD subsidies, and $44 million in funding from the City of Cambridge. Unlike BHA’s recent development efforts, CHA’s project is 100 percent affordable, with many units set aside for extremely low-income residents. CHA is placing much less of an emphasis on cross-subsidization and mixing incomes and is prioritizing deep affordability.

Development and ownership structure

CHA has a long history of innovation in preservation and development and began using Faircloth-to-RAD before many other PHAs. It has now begun working as a consultant and development partner with other PHAs that have unbuilt Faircloth authority – particularly small PHAs in the Boston region that do not have the technical expertise to make full use of HUD’s financing tools. Massachusetts allows PHAs to operate anywhere in the state, which enables CHA to blend its own subsidies with those of PHAs in other towns and cities and operate across town lines. Given the complexity of some of these projects and the fact that Faircloth-to-RAD subsidies are often insufficient to generate new housing units on their own, CHA sees these consulting partnerships with other PHAs as an important effort to operationalize Faircloth-to-RAD.

Additional tools used

Affordable housing and related uses on land owned by CHA benefit from a full property tax exemption.

Public housing conversions group

Overview

- Under the Ka Lei Momi project, the state plans to construct new affordable and workforce housing on nine existing properties by leveraging the Faircloth-to-RADA program that allows PHAs to build new public housing units and immediately convert them to units with project-based Section 8 contracts. In doing so, PHAs must remain within their “Faircloth Limit,” that is, the number of units they owned or operated as of 1999. program.

- In addition to the Faircloth-to-RAD program, the Hawaii Public Housing Authority (HPHA) recently received approval from the Hawaii State Legislature to build mixed-income housing and allow for the cross-subsidizationA financing structure in which income produced by units priced at the market rate is used to subsidize the costs of affordable homes at either the building or portfolio level. of affordable units.

- The Ka Lei Momi Initiative is projected to create a minimum of 10,000 new units across the state.

Description

Motivation

Hawaii faces skyrocketing rents and a pressing shortage of affordable homes. The state also has one of the highest rates of homelessness in the country. Hawaii has turned to public development models to remedy these challenges, with the Hawaii Public Housing Authority (HPHA) playing a central role.

Governance structure

HPHA is governed by an 11-person board of directors appointed by the governor and overseen by the state legislature.

Financing model

Under the Ka Lei Momi project, HPHA will finance new units via RAD conversion of both existing public housing units and unbuilt Faircloth authority, as well as supplemental funding from HPHA’s Moving-to-Work (MTW) funds, LIHTC, and private equity financing through Highridge Costa.

Housing projects

HPHA and the Highridge Costa Development Company recently received permitting and financing approvals to begin the redevelopment of Mayor Wright Homes in Honolulu. The project will convert the existing property of 364 public housing units into a mixed-income community with 2,448 new units through the Faircloth-to-RAD program. Development will begin in 2025 and continue through the next 15 years. HPHA will create additional units across eight other properties.

Development and ownership structure

HPHA and Highridge Costa will work together to build and manage 10,000 new units of affordable and workforce housing on nine properties already owned by the HPHA.

Additional tools used

Beyond the Faircloth-to-RAD program, the authority also received approval from the Hawaii State Legislature to build mixed-income housing on its land. Rental income from market-rate units will cross-subsidize the affordability of income-restricted units.

Affordable housing group

Overview

- In 1971, the county created an independent legal entity known as the Community Development Agency (CDA). This agency relies on a special property tax levy

An ordinance that creates a new tax or sets aside existing tax revenue specifically to fund affordable housing development.

and a common bond fundA financing structure in which new bond issuances are amended to join a single, large bond, allowing agencies to pool revenues and costs across housing projects.

to finance and build new affordable housing for seniors. - In addition to these tools, the CDA benefits from a property tax exemption.

- Today, the CDA owns and operates more than 1,700 senior units in nearly 30 properties.

Description

Motivation

Dakota County originally created the Community Development Agency (CDA) as a housing and redevelopment authority that oversaw the Housing Choice Voucher program. Over time, the CDA would increasingly focus on affordable senior housing in partnership with the county. Today, the agency is both a public housing authority and a housing finance agency.

Governance structure

During the first 20 years of the CDA’s senior housing program, the Dakota County Board, which is elected, appointed the CDA’s Board of Directors. In approximately 2010, however, members of the county’s board appointed themselves to serve as the CDA’s board. This has the effect of holding the CDA directly accountable to county residents for high-quality development and fiscal responsibility.

Financing model

Minnesota state statute allows the CDA to issue tax-exempt “essential function” bonds, which are credit enhanced with a general obligations pledge from Dakota County, to finance new senior housing developments. Each new bond issuance is amended to join one large common bond, which allows the CDA to pool revenue from across its developments to service the debt. Aggregating all operating revenue and costs also allows the CDA to spread out the cost of any major repairs, such as new roofs, windows, and siding. Importantly, in addition to its rent revenue, the CDA relies on a special property tax levy authorized by the Minnesota Legislature in 1999 to help service its bond debt. As a result, Dakota County’s backing of the bonds is strictly a credit enhancement; it does not use its own tax receipts to service the bond.

Housing projects

Today, the CDA owns and operates more than 1,700 senior units in nearly 30 properties. Initially, the CDA set a minimum and maximum rent for each building and residents paid 30 percent of their income towards rent within that range. More recently (for the newest 10-12 buildings), the agency has transitioned to a flat rent structure. Because most of its projects are small (the CDA now aims for ~65-unit buildings), cross-subsidization is less feasible, and the agency has not pursued a mixed-income approach to date.

Development and ownership structure

Typically, the CDA begins construction on a new senior housing development immediately after floating a new bond without the need for separate construction loans. The CDA typically chooses a general contractor through a public bidding process rather than negotiating the contract, and then withdraws the necessary funds to make each monthly construction payment. The agency pays a sales tax on the construction contract but can obtain a rebate on construction materials from the state at the end of construction. The CDA fully owns its senior housing developments; it also has its own maintenance staff and conducts all property management in-house.

Additional tools used

Another important aspect of the development package is that the CDA is exempted from property taxes, though it does pay a Payment In Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) in order to help pay for public services for its affordable senior projects.

Affordable housing group

Overview

- The Housing Company (THC) relies on public land strategies

Practices, such as land banking, that leverage vacant, underdeveloped, or otherwise available parcels for new construction.

and a property tax exemption to facilitate development across the state. - As a nonprofit developer that uses Low-Income Tax Credits (LIHTC), THC does not meet criteria established in our recent report for public development and ownership. Nevertheless, its public mission and relationship with the Idaho Housing Finance Association (IHFA) make it a relevant case study.

- To date, THC has developed 2,010 units across 48 projects.

Description

Motivation

The Idaho Housing Finance Association (IHFA) is the state’s self-sufficient housing finance agency, operating much like a nonprofit. In 1992, in response to the underutilization of LIHTC in the state, the IHFA created The Housing Company (THC) to be a 501(c)(3) nonprofit development and property management organization.

Governance structure

THC’s Board of Directors is comprised of 50 percent independent members and 50 percent IHFA-appointed members. Rules established to clearly distinguish THC from IHFA, combined with the straightforward and transparent nature of the state’s Qualified Allocation Plan, which guide how IHFA awards federal tax credits, are key in protecting THC from a perception of a conflict of interest due to its relationship to IHFA. Experts in Idaho expect that this model may be hard to replicate today because developers may view a similar entity as a competitor with an unfair advantage for receiving tax credits.

Financing model

THC acts much like a typical affordable housing developer. It commonly relies on LIHTC – both the 4 percent and 9 percent credits. THC projects also use Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) funding when it is available. THC has used HOME funding for several of its rural projects, which are usually smaller in size, from 6 to 15 units per project. These donations help subsidize the development of single-family homes, which may have deed restrictions to maintain long-term affordability or follow a shared-equity model. In recent years, THC successfully accessed $50 million of American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds, used in combination with 4 percent credits, to create approximately 1,200 workforce units. This is a model that THC would like to replicate with future funds from the state.

Housing projects

THC has developed 2,010 units across 48 projects. These units are close to 100 percent affordable.

Development and ownership structure

THC manages, and to some extent owns, all of its properties. With tax credit projects, the investor LLC holds majority ownership in the project while THC only owns a small stake, but THC includes a provision that passes full ownership to the organization after the compliance period. By serving as a property manager, THC can and does exercise the option to raise rents more slowly than the market would merit, thereby keeping units as affordable as possible. All of THC’s projects include some affordability component, and they typically establish a preference for voucher holders.

Additional tools used

THC’s public land strategies leveraged Idaho’s considerable surplus of public land to finance and develop affordable housing statewide. Low-income housing owned by nonprofits like THC also benefits from property tax exemption in Idaho.

There are a number of regulatory tools and key financing mechanisms that can facilitate public development and ownership of housing.

The three models demonstrate that a variety of interventions are necessary to facilitate public development. These may include financing tools, such as revolving loan funds and tax-exempt bond recycling, as well as regulatory and programmatic tools, such as self-insurance and special tax levies.

To explore the potential impact of these tools, and learn more about how localities are implementing them, use the table below.

Table 1. Public Development Tools

Publicly driven housing development, however, just like any development, relies on the right economic conditions to work.

For example, mixed-income housing models may rely on cross-subsidization (where higher rents in market-rate units subsidize affordable rents in rent-restricted units within the same property). We worked with Forsyth Street, a consulting firm specializing in affordable housing finance, to develop a simple, interactive tool that can help users better understand how market rents, development costs, and operating expenses might affect development, and how public financing tools could help close the gaps.

Download the Excel workbook below and visit the different tabs to explore how property tax exemptions, more favorable financing, higher rents, and other interventions can affect the financing gap for a hypothetical 100-unit mixed-income multifamily housing project. The inputs in the workbook are based on Rhode Island’s housing market and lending environment but can be adjusted to reflect the realities of your own jurisdiction.

U.S. localities can learn from social housing models overseas

Advocates for social housing have drawn inspiration from international examples like Vienna and Singapore. These models often entail durable affordability, collective ownership, and broad eligibility. The form that social housing systems take varies greatly due to their different political and economic contexts. Nonetheless, these models offer valuable lessons on rent structures, the use of public land, and how public agencies can interact with nonprofits to deliver decommodified housing at scale.

Overview

- Vienna’s more than 420,000 social housing units, which make up more than 43 percent of the city’s housing stock, are split between two housing systems: one municipal, and one made up of tightly regulated limited-profit associations.

- Social housing rents are calculated based on the cost of developing, operating, and maintaining housing.

- In some Viennese social housing, tenants contribute equity to help cover the costs of land acquisition and construction.

- Low-cost development loans issued to limited-profit housing associations are partially revolving; as they are repaid, each region reinvests in new development.

- After these loans are repaid, rents decrease to a level sufficient to cover day-to-day administration, maintenance, and renovations.

Description

Background

In Vienna, social housing accounts for more than 43 percent of all housing units – one of the highest proportions in the world. These units are nearly evenly split between two social housing systems: “municipal housing” built and owned by Wiener Wohnen, a city-owned company whose budget is approved by the Viennese City Council, and “limited-profit housing” built by limited-profit housing associations (LPHAs). Both systems exclusively produce rental housing, owned indefinitely by either the municipality or an LPHA (except for right-to-buy units; see information on tenant equity contributions below). They also both base rents on the cost of developing and maintaining the housing and have broad eligibility criteria, such that households of varying income levels and sociodemographic backgrounds can access this housing stock. It is worth noting, however, that Viennese social housing exists in the context of the Austrian welfare state, in which healthcare, childcare, higher education, and other major expenses are spread over the tax base. Housing costs may be less burdensome in this context.

LPHAs can be organized as limited liability companies, public liability companies, or cooperatives, but in order to receive LPHA status and access low-interest government loans, they must abide by an Austrian law (the Wohnungsgemeinnützigkeitsgesetz, or WGG) that dictates how they calculate the cost of a given development. The law prohibits them from charging rents above or below the cost-recovery level for a given development.

How is new development financed?

Municipal housing in Vienna is financed primarily by a federal income tax. The government distributes a portion of the tax revenue to each of Austria’s nine states, which decide whether to use it for housing construction or subsidies (since the early 2000s, they may also invest it in infrastructure). The city has an annual budget for new development and renovation of about $700 million, of which $530 million comes from the national government.

Financing for limited-profit housing is more complex. New LPHA developments are usually financed with the following:

- A low-interest, subordinate loan from the regional government, making up 30-40 percent of the capital stack

- A bank loan, also making up 30-40 percent of the capital stack, typically with a 25-30 year term and an interest rate of 1-1.5 percent (when interest rates increase, special-purpose housing construction banks offer affordable rates)

- Equity from the LPHA itself, comprising 10-20 percent of the stack

- A tenant equity contribution making up 5-10 percent of the total investment

- Additional public grants, often 5 percent of the stack, to cover the expense of meeting secondary policy objectives such as adding renewable energy sources

The regional low-interest loans that finance LPHA development are, in part, revolving. Historically, as LPHAs repaid their loans, regional governments were required to reinvest these funds in new development. This statutory obligation no longer exists, but LPHA loan repayments still account for about two-thirds of the funds used to issue new LPHA development loans. The remainder comes from the regional government’s own revenue, often drawing on a regional housing-specific tax of 1 percent on gross salaries. LPHAs do not have to service the interest on these regional loans until their other loans have been repaid.

The City of Vienna also subsidizes social housing, where possible, through public land. Wohnfonds Wien, a public land bank, has been acquiring public land for the last 40 years. To be granted an opportunity to buy public land or, more recently, access it via a 99-year ground lease, LPHAs must go before a jury and, if the project is large, compete against other proposals. Entries are judged based on economic feasibility, ecology, architectural quality, and social sustainability criteria. Municipalities can also specially zone land for LPHA housing, helping to limit the cost of land. Nevertheless, rising land prices combined with cheap financing available on the private market for non-social housing have dampened LPHA production in recent years. Conditions are only now becoming more favorable due to rising interest rates.

Tenant equity contributions are another distinctive component of LPHA financing and are often employed when a development incurs high land acquisition or other upfront costs. In this model, tenants must make a down payment at move-in. These down payments have risen significantly in recent years because of the rise in land prices. In Vienna today, they may vary between €200 and 800€ per square meter ($20-80/ft2), and so could reach 30.000€ ($32,400). The down payment is returned to tenants – minus a deduction of one percent per year – when they move out. Tenants whose down payment exceeds a certain amount have the right to buy their unit after a tenancy of five years. Nevertheless, the tenant equity contribution represents a significant barrier for some, so Vienna offers loans to cover it. The absence of this requirement in Vienna’s municipal housing makes it more accessible than LPHA housing for low-income households.

How are rents determined, and how affordable are they?

In Vienna, the government bases social housing rents on the cost of developing and maintaining a given project. The WGG, which regulates rent calculations in limited-profit housing, factors in all planning, construction, financing, and management costs for a development. Because calculations must occur at the level of an individual development, cross-subsidization between developments – even those owned by the same LPHA – is impossible. Once the LPHA’s loan is paid off, a development’s rents typically decline, though not precipitously. LPHAs continue to charge a base rent (set by the WGG at 1,87€/m2 in 2021, updated every two years, and indexed to CPI), plus maintenance, service, and renovation costs. The LPHA reinvests surpluses in new development. Meanwhile, in Vienna’s municipal housing, rents are set by the city in line with federal rent regulation laws and are slightly cheaper than LPHA rents.

In 2016, average monthly rents in Vienna’s municipal housing were 3,97€/m2 (40¢/ft2), compared to 4,84€/m2 in limited-profit housing and 6,34€/m2 in private housing. A version of LPHA housing called “smart housing,” which has efficient ground floor plans and fewer amenities, also offers lower rents and down payments. Social housing recipients may also be eligible for a housing allowance – but these are fairly rare in Vienna.

Together, the municipal and LPHA systems have helped keep housing affordable in Vienna. In 2020, only 10 percent of households reported that meeting their housing needs represented a “heavy financial burden,” compared to nearly 30 percent in the EU as a whole.

Who is eligible for social housing?

Social housing is available to much of the Viennese population. The application process and basic eligibility requirements for municipal and limited-profit housing are the same; the 2023 after-tax income cap of 53.340€ ($57,600) for an individual – and higher amounts for larger households – qualifies about 75 percent of the population. Municipal housing is now additionally restricted to those who have lived at their current address in Vienna for at least two years; this was introduced as an “exclusion mechanism” in the early 2000s as a response to rising international migration. Tenants in both municipal and limited-profit housing can only receive a unit that fits their current household size (with some exceptions), and municipal housing is prioritized for those with urgent needs, including cost-burdened residents or those living in overcrowded conditions or doubling up.

How has this model changed over time?

Vienna’s social housing system dates to the 1920s, when the city’s Social Democratic government built 60,000 municipal apartments in vast “people’s palaces” (Wolkswohnungspaläste). Today, Wiener Wohnen owns and manages about 221,000 units in Vienna. The city’s 58 LPHAs manage another 200,000 units. Between 2001 and 2020, there was a net increase of about 60,000 units of social housing units in Vienna. The massive scale and age of the social housing system in Vienna creates advantages that would be hard to replicate elsewhere; buildings whose mortgages have long since been paid continue to generate rent revenue that can be used to cover repair needs and invest in new development, and the system is so established that it is immune from the whims of politics. On the flip side, there have not been any new LPHAs founded in Vienna in the recent past, as it is difficult to enter the social housing space.

Overview

- Social housing accounts for nearly a fifth of Helsinki’s housing stock; the city’s municipal housing association maintains about 50,000 units.

- After mortgage loans guaranteed by the national government are repaid, rent restrictions on social housing expire, and municipal and nonprofit housing associations are free to privatize the housing or raise rents.

- Although, as in Vienna, rents are cost-based, housing associations have the ability to “equalize” them across their portfolios. This means that rents for new construction can be kept lower.

Description

Background

In Helsinki, social housing accounted for 19 percent of the housing stock as of 2020, compared with 11 percent of the housing stock in Finland as a whole. The Finnish social housing sector bears some resemblance to Vienna’s dual system of municipal and limited-profit housing associations. ARA, the national agency regulating social housing, partners with about 800 social housing providers across the country. These can be either municipalities (or housing associations principally owned by a municipality) or ARA-approved nonprofits specializing in social housing development. In reality, up to 80 percent of social housing in Finland is managed by municipally-owned housing associations. The largest provider in the country, with about 50,000 units, is Heka, Helsinki’s municipal housing association.

The most important aspects distinguishing Finland’s system are: 1) new social housing is financed primarily by bank loans, which are guaranteed and have interest subsidized by the state; 2) after these loans are paid off, the rent restriction period comes to an end and the social housing provider has the option to gradually increase rents, privatize the units, and/or decide on their own allocation criteria; and 3) social housing providers in Finland (unlike in Austria) are permitted to equalize rents across their stock, making some cross-subsidization possible.

How is new development financed?

The principal financier of social housing in Finland is MuniFin, a bank collectively owned by the Republic of Finland, Finnish municipalities, and the public sector pension fund. MuniFin finances not just housing but schools, hospitals, and other infrastructure, and grants loans with terms of up to 41 years. It lent €827 million for new social housing in 2020 and made a net profit of €197 million. Loans from MuniFin and other private financial institutions typically make up 95 percent of the cost of developing a new social housing project, but ARA guarantees loans to reduce risk and improve the loan terms. As interest rates currently exceed 3.9 percent, the state has intervened further to reduce debt service costs for social housing providers. Providers must invest the remaining 5 percent in the development cost, either out of their own savings or via a separate, non-guaranteed bank loan.

The City of Helsinki owns a large amount of land, which represents an important factor in affordable development. The city leases land to social housing providers at about 10 percent below market rent. Other cities have chosen to sell public land directly to social housing providers. In either case, the ARA sets a maximum price, or rent that is pegged to the social housing provider’s market value.

How are rents determined, and how affordable are they?

Rents in Finland’s social housing are regulated by the ARA, which caps them at the cost of providing the housing, factoring in development, maintenance, renovation, and administration costs. A key distinction from the Austrian cost-based model is that Heka and other social housing providers can “equalize” rents across their entire stock – including units whose mortgages have been repaid and are therefore no longer rent-restricted, as long as the effect is to lower rents in the restricted units. This means that rents can be low even in newer, more expensive housing, and the cost of major renovations or repairs can be spread out across a large group of tenants.

About 40 years after construction, when the loans for a social housing project have been repaid, cost-based rent rules no longer apply. The ARA can also end the restriction period for a project early if, for instance, population decline has resulted in an oversupply of social housing and it is challenging to find households willing to pay the cost-based rent. Generally, though, the projects are still owned by the same municipal housing association at the end of the restriction period, and the same social motivation remains. Studies show that rents do not change after the rent restriction period in about 80 percent of cases.

The differential between private and social rents is especially large in high-demand areas like central Helsinki. In 2017, social housing in Helsinki rented for an average of 12,75€/m2 ($1.28/ft2), compared with 19,58€/m2 ($1.96/ft2) for market-rate units. Low-income households may also be eligible for rental assistance.

Who is eligible for social housing?

All households are theoretically eligible for social housing in Finland. In practice, preference is given based on the household’s income, wealth, and urgency of need. Helsinki’s allocation process is somewhat opaque but designed to promote a social mix, ensuring that people who all speak a specific language or who are all unemployed are not concentrated in a single building. About 3,000 social apartments become available in Helsinki every year, but there are 10,000 applications in the queue at any given time. Applicants must reapply every three months until they are selected.

How has this model changed over time?

Finland’s social housing sector underwent a major change in the late 1990s, when two major nonprofit developers transformed their business strategy and became real estate investors. They have since converted and sold off most of their social housing stock. Nevertheless, the overall share of social housing in Helsinki has remained stable thanks to municipal production of about 3,200 new units between 2001 and 2020.

Finland is experiencing a slow shift away from promoting housing affordability purely through social housing production and toward subsidizing housing costs for low-income households. This shift jeopardizes the many advantages that a large stock of social housing brings, including very high-quality, affordable housing in desirable neighborhoods. There is also ongoing political debate about whether the government should periodically verify income for social housing tenants in order to encourage those with rising incomes to transition to private housing. Helsinki, however, has opposed this proposal.

Overview

- Over 500 nonprofit housing associations in Denmark have produced more than 560,000 social housing units, making up about a fifth of the housing stock nationwide.

- Nonprofit housing associations collaborate closely with municipalities to decide when, where, and how much social housing to build and to allocate units to applicants.

- After mortgage loans are repaid, rents remain steady, and the revenue formerly used to service the loans flows into a National Building Fund used to make major renovations, invest in new construction, and fund programming for social housing residents.

Description

Background

Denmark’s social housing sector is, in reality, a nonprofit housing sector. There are over 500 nonprofit housing associations in the country, all of which have the same basic legal structure and produce exclusively rental housing. These nonprofits have produced over 560,000 housing units, making up about 20 percent of the Danish housing stock as of 2021.

This housing type is perceived as “social” for two reasons. First, as in Austria and Finland, rents are purely cost-based. National law requires that the income and expenditures of nonprofit housing organizations match, and rents must be determined annually based on an operating budget for the coming year. The state also sets a maximum per-square-meter cost of new nonprofit housing construction by housing type and region, which helps keep rents low. Second, municipalities – including Copenhagen – work closely with nonprofit housing associations to decide how much and where to build and have the right to directly administer the tenant screening and selection process for a quarter of the units in every development. In exchange, municipalities typically pay about 10 percent of the cost of new construction. Every year, municipalities and nonprofit housing associations engage in “dialogues” in which they jointly plan for new construction.

How are renovations financed?

A distinctive aspect of the Danish system is that when the mortgage is paid off for a given social housing project, its rents do not decrease. Instead, they continue to increase in line with a national home price index until the 45th year after loan take-up, after which the nominal rent level is maintained in perpetuity. The share of rents previously used for debt service then flows into a National Building Fund (NBF). Denmark uses the NBF to subsidize renovations, fund social programs, and sometimes invest in the construction of new social housing, for example, through the remediation of environmentally damaged sites. The NBF is a critical element in the social housing system; it creates a permanent, dedicated stream of revenue for social housing and prevents politicians and residents from perceiving social housing tenants as welfare-dependent.

How has this model changed over time?

In 2015, Denmark began encouraging municipalities to set aside up to a quarter of large new developments for social housing units. This policy was intended to address the reality that developing social housing is more difficult during economic growth periods when land prices soar. So far, this approach has been principally tested only in the major cities of Copenhagen and Aarhus, and will be formally evaluated in 2024-2025. One early problem with this approach is that the nonprofit-developed social housing units were often the last to be built, and so their rents were set when construction costs were the highest. A new law has forced a stop to this practice, and a single developer now typically builds the entire complex at once, handing the keys to the nonprofit for the social units when they have been constructed.

Overview

- Singapore’s public housing stock houses nearly 90 percent of the population.

- Although Singapore’s housing authority retains perpetual ownership of the land on which social housing is built, residents can buy, sell, and inherit units, making them valuable commodities that can build residents’ wealth over time.

- Mandatory personal savings accounts for every employed person are the principal way residents pay their mortgages, as well as a fund the government borrows against.

- New development occurs on a build-to-order basis (i.e., prospective residents “order” a unit, and ground does not break on a new social housing project until 70 percent of its units have been bought).

- Public land and low-cost imported labor from South Asia keep development costs low.

Description

Background

Singapore’s social housing system is of a scale and design that wholly departs from those in Europe. Beginning in the 1960s, Singapore’s Housing and Development Board (HDB) began churning out massive, high-rise projects as a way to combat informal communities (kampongs) forming on the urban periphery. This public housing stock, which exceeds a million units and continues to grow, currently houses nearly 90 percent of the country’s citizens and permanent residents.

Singapore’s homeownership model

There are several especially noteworthy aspects of Singapore’s model. First, a large majority of social housing residents are effectively homeowners because they can buy, sell, and inherit their government-built units – though in reality, HDB sells them a 99-year lease, and the agency perpetually retains ownership of the land on which social housing is built. As of 2021, only 3 percent of the resident population are renters. In 2021-2022, the price of a typical one-bedroom unit ranged from SGD $372,000 to SGD $525,000 (USD $276,000 to USD $389,40). Generous housing grants are available to first-time homebuyers with lower incomes.

A mandatory savings scheme

Second, Singapore has a unique way of financing this public homeownership. The country’s Central Provident Fund (CPF), which started out as a retirement savings scheme, creates a compulsory savings account for every employed Singaporean. Account holders contribute 20 percent of their wages and their employers contribute another 17 percent each month (note that these contribution rates fluctuate with the economy and reached as high as 25 percent from both individuals and employers in the early 1980s). The Singaporean government sells bonds to the CPF board in order to access CPF savings, which are then used to finance the public building program through various loans and grants to the HDB. Meanwhile, beginning in the 1960s, the government began allowing individuals to withdraw from their CPF accounts before retirement. This has allowed CPF accounts to become the primary way that families repay their HDB mortgage loan; no private financial institutions are involved in the transaction.

Keeping development costs low

A third salient characteristic of the Singapore model involves the nation’s strategy for keeping development costs low. An eminent-domain-style land acquisition program dating to the 1960s means that the government today owns 90 percent of the country’s land, and it awards construction contracts for entire urban districts to private construction companies whose only customer is the state. Another important feature is cheap, foreign labor. Singapore does not have a minimum wage and relies on low-paid temporary workers from elsewhere in South Asia to construct new social housing. These workers are not eligible for HDB housing and live in crowded dormitories.

In addition, in response to a period of oversupply when HDB units were sitting vacant, the agency has shifted to a build-to-order model. Prospective residents purchase an apartment plan, and HDB begins construction on a new project only when 70 percent of units have been presold. This strategy creates upfront financing for the government but also leads to longer waits (3 to 5 years on average) for households acquiring a new unit.

How has this model changed over time?

Ultimately, the structure of Singapore’s model creates a delicate balancing act for its government. There is an active resale market for HDB units, and resale units can be significantly more expensive than HDB units. Singaporean homeowners, of course, benefit when home prices rise, as this increases the value of the asset that represents their retirement savings. The HDB must try to protect the appreciation of existing units while also providing affordable units to newly formed households.

Another consideration is how to help Singapore’s aging residents tap into the value of their homes as they retire. The government has created two new programs to help retirees accomplish this. Very low-income retirees are allowed to sell their lease back to HDB in exchange for a monthly income without having to vacate their unit. Others are allowed to sublet, creating a stream of income while still allowing them to bequeath their home to their children.

Overview

- Hong Kong’s region-wide housing authority owns more than 800,000 units of public rental housing and also builds and sells apartments.

- The housing authority owns a diverse portfolio of commercial and residential property. The revenue from leasing these assets and from selling some units as homeownership housing helps subsidize public rental housing.

- Deep and direct investment by the Hong Kong government, including grants of public land, infrastructure, and social programming, help the housing authority keep rents extremely low in a high-cost market.

Description

Background