Two years after participating in the Housing Solutions Workshop in 2021, Bethlehem released a comprehensive housing plan this October.

By Ben Hitchcock

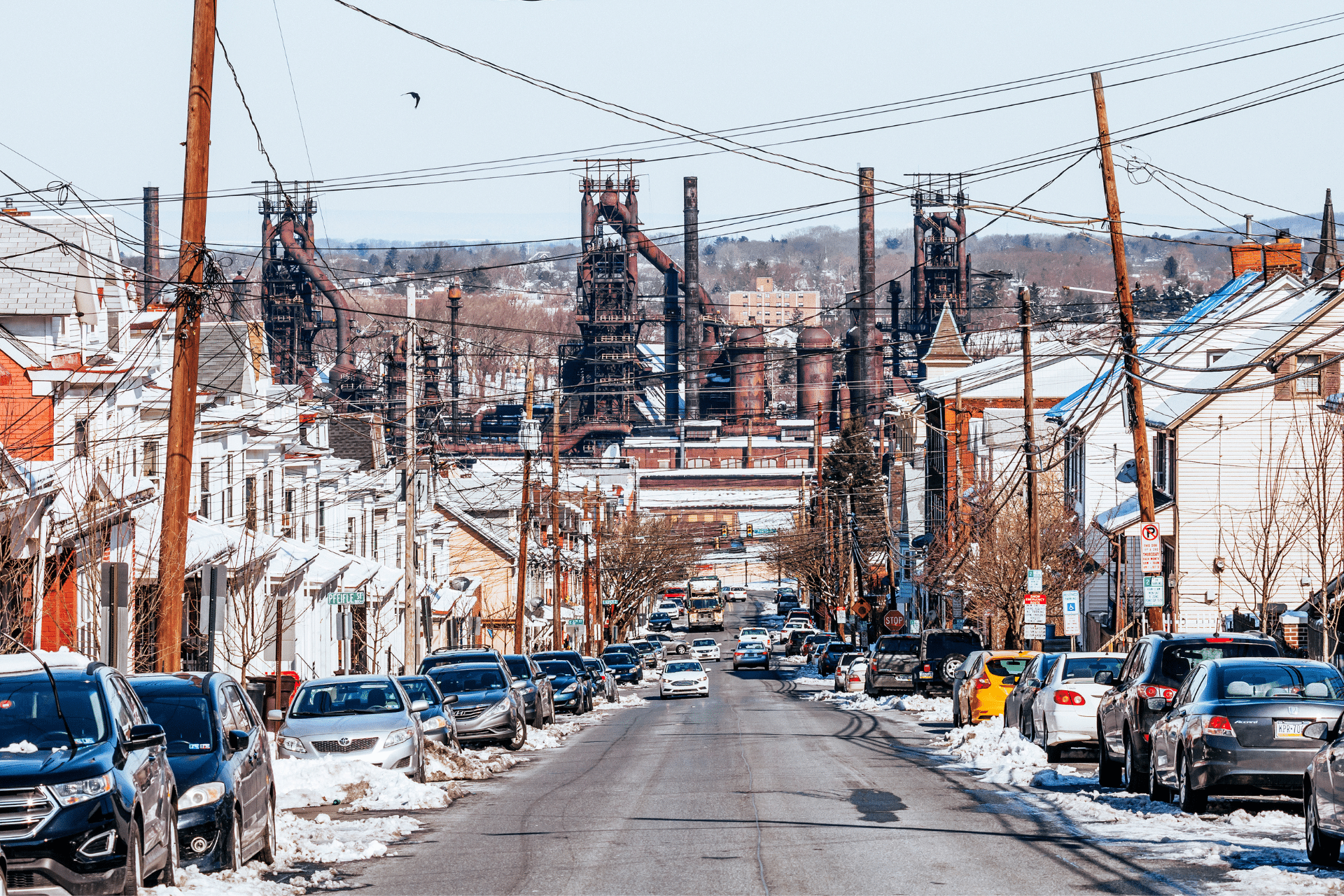

When Bethlehem Steel’s famous factory went out of business in 2001, the town that had forged the Empire State Building’s girders and the ships of World War II shuddered. But unlike many hollowed-out Rust Belt cities, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania came back strong. So strong that the city today has a problem it never expected: so many people want to live in Bethlehem that, since the pandemic, the city has fallen into an intense housing affordability crisis.

Ninety minutes away from both Philadelphia and New York, Bethlehem is home to bustling and selective Lehigh University. With a population of 76,000 people, the city has a small-town charm with an array of big-city amenities. It’s transformed since the closure of the factory, and in recent years has drawn more and more new residents.

The rusted smokestacks of Bethlehem Steel now rise above a performing arts venue, symbolizing the town’s evolution. Photo credit: Associated Press.

Such rapid change has brought growing pains, however. Like in many other small cities around the country, Bethlehem’s housing market has become increasingly unaffordable. From 2019 to 2023, median home sale prices increased 66 percent, from $182,000 to $302,000, and median rents rose 41 percent, from $1,354 per month to $1,910, according to a presentation of the city’s Comprehensive Housing Plan. Incomes have not kept up with the soaring costs of housing, and more than 8,300 low-income households pay more than 30 percent of their income on housing–the federal threshold of being cost-burdened.

Local rental vacancy rates also signal a crisis—just two percent of units are vacant, well below the seven to eight percent generally considered healthy for a city, according to a study of Bethlehem’s market by a team of consultants. New construction has reshaped the city but still has not kept up with demand for affordable living options for people with low- and moderate-incomes.

“Housing wasn’t the biggest issue in our city three or four years ago,” Bethlehem Mayor J. William Reynolds said in an interview with the NYU Furman Center’s Housing Solutions Lab, “but it’s definitely been the biggest issue in our city as we exit the pandemic.”

As rising rents and prices cause pain in small and midsize cities across the United States, Bethlehem offers a case study in how a housing crisis happens, and what a city can—or cannot—do to address it.

"There's no silver bullet as we all know—it will take a comprehensive and balanced approach to make progress in addressing the affordability crisis."

Jess Wunsch, Director of City Engagement at the Housing Solutions Lab

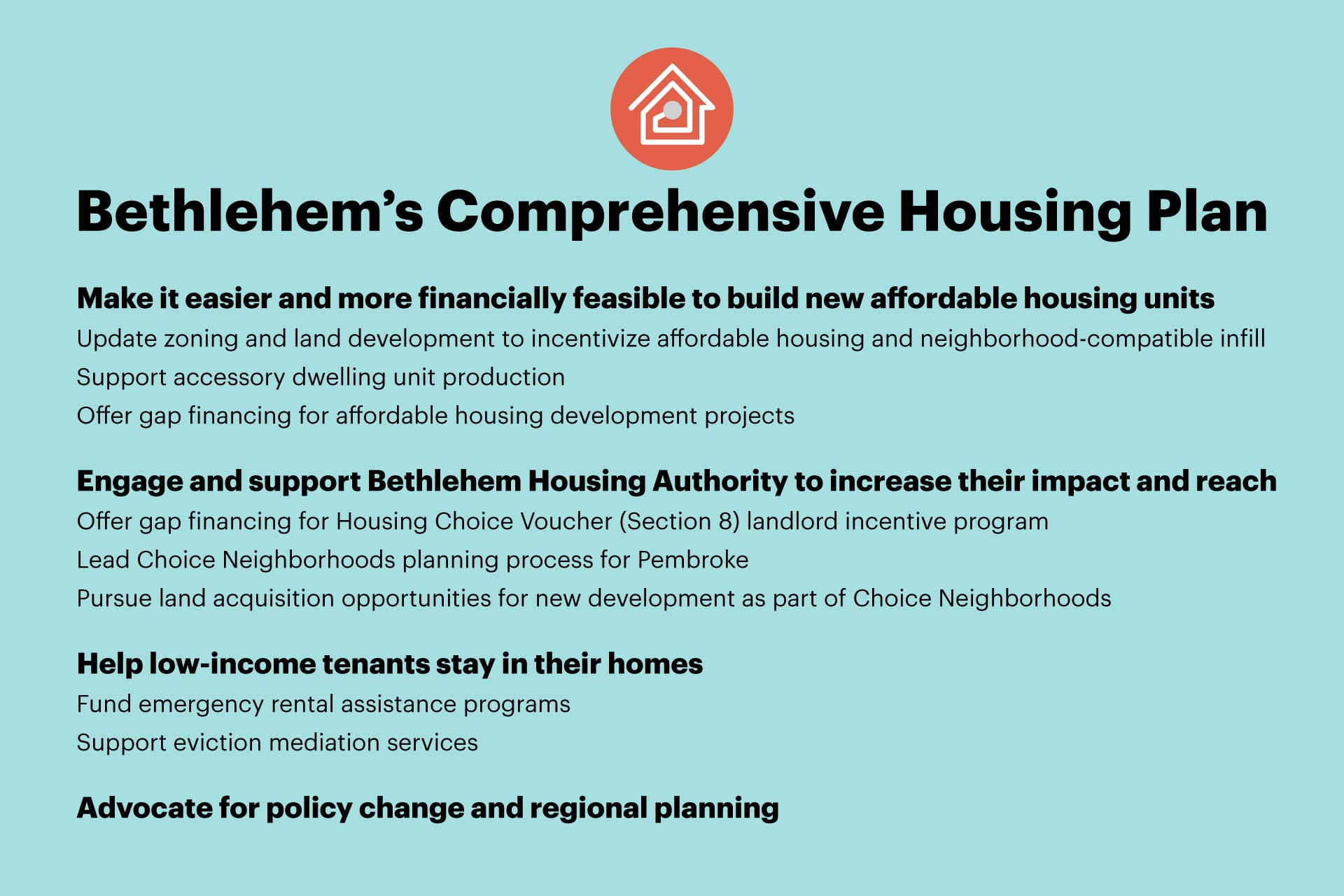

Two years after participating in the Lab’s Housing Solutions Workshop in October 2021, this fall Bethlehem released its new Comprehensive Housing Plan, the result of data-driven research and a detailed housing needs assessment. The city’s sweeping proposed plan would remove barriers to housing construction, offer incentives to landlords who accept housing vouchers, help tenants at risk of displacement stay in their homes, and more. The city also plans to propose updated zoning and land use ordinances to permit a variety of housing types and encourage infill development.

“This is the goal of the Housing Solutions Workshop,” said Jess Wunsch, Director of City Engagement for the Housing Solutions Lab. “It is designed to support city leaders in assessing their jurisdiction’s housing needs and the existing policy landscape and learn about the suite of policy options available.

“There’s no silver bullet as we all know – it will take a comprehensive and balanced approach to make progress in addressing the affordability crisis.”

'Dozens of calls a week'

In recent years, Bethlehem’s rental market has often felt more like Manhattan—affordable units rarely go on the market, and as soon as a listing pops up, ten families arrive to compete for the lease, said Anna Smith, the director of Community Action Development Bethlehem, a nonprofit that runs a variety of development initiatives in the city.

The competition means that people who have an eviction history, single parents with large families, and people who cannot immediately fork over two months of rent and a security deposit are out of luck.

“I like being attractive to people from the outside,” said Marc Rittle, the executive director of New Bethany, a nonprofit in Bethlehem that helps resettle those facing housing insecurity and operates some of its own housing units. “But if we’re going to grow that much and not be able to grow the housing stock at the same rate, that becomes frustrating.”

The tight housing market has made it harder to find places to live for New Bethany’s clients, like Yarieliz Torres, a single mother of three. “We have really great caseworkers on staff,” said Rittle, who was part of the team that participated in the Lab’s 2021 workshop. “If they can’t find places, truly they’re not there.”

Torres lost her job during the COVID pandemic and moved to an apartment in nearby Allentown, but soon after, the building was condemned, and she became homeless. For six months, she and her children slept in motels and in her car, navigating the overburdened social service system and trying to get help. “I felt destroyed, I felt like the whole world caved in,” Torres said through a translator. “It was really hard for me to see my kids have nothing.”

Today, Torres works at a bodega and takes her children to a reliable daycare. She says she’s proud of the progress she made, and is thankful that New Bethany. The nonprofit covered a temporary hotel stay for and her children and helped her find a house and paid her immediate expenses, like the security deposit and first three months rent. Now, she’s able to cover her own housing costs. “It feels really good to be with my kids and feel safe,” Torres said.

The challenges that Torres faced have become more and more common in Bethlehem.

While overall point-in-time-numbers are lower than in 2022, eviction rates have increased as the costs of rent and food are escalating. The Lehigh Valley Planning Commission reports a shortage of nearly 15,000 rental unit for households making under $25,000 a year, increasing the likelihood of homelessness for low-income members of the community.

Rittle said New Bethany has seen a 112 percent increase in customers at its food pantry, and has doubled its staff to keep up with the demand for housing services in the last couple of years. “We’re getting dozens of calls a week—and sometimes a day—for ‘I think I’m going to be evicted, I can’t pay my rent, I’m short a utility bill,’” Rittle said.

A street in Bethlehem. Photo credit: Getty Images.

'Can't afford to stay here'

Bethlehem’s housing market has been squeezed by people moving in from out of town, but the expansion of Lehigh University has also caused pressure in the Southside—a neighborhood where waves of immigrants throughout American history have been able to get a foothold.

“We have young families starting out,” said Smith. “You can talk to people all over the city of Bethlehem and they’ll say, ‘My first house was on the Southside.’ It was affordable, working class housing.”

This part of town has felt the housing crisis particularly acutely as leaders at Lehigh have also sought to expand the university’s student base and footprint. In 2016, the school’s board approved a plan, dubbed the “Path to Prominence,” which aimed to increase total enrollment by 20 percent over a seven-year period. Currently, Lehigh has more than 5,600 undergraduates, and 35 percent of them live in off-campus housing. The vast majority of that housing is located in the Southside.

“We have an influx of people coming into Bethlehem, and it’s a mixed blessing,” City Councilmember Grace Crampsie Smith said. “But the flip side is the people that have lived here all their lives, they can’t afford to stay here. Their children have to stay and live with their parents or they just can’t get out on their own.”

The university has always had a considerable off-campus student presence, but not too long ago, the majority of the housing was owned by small landlords with ties to the community, Smith said. But that’s now changing.

For example, Amicus Properties, a landlord company that specializes in luxury student housing, owns rentals at a dozen campuses around the country. It now operates more than 100 properties in Southside Bethlehem with many of its property doors painted bright yellow.

A Street View image from Google Maps of a building owned by Amicus Properties.

Large investors buying up single-family homes to rent out as investment properties is a concern commonly heard in some larger cities in the South and West, like Atlanta, GA; Phoenix, AZ; Las Vegas, NV; and San Jose, CA.

“All of a sudden, in 2017, 2018, you see these national companies coming to town, paying astronomical prices for these properties and then renting them out to students at up to $1,000 per bedroom,” Smith said. “We started seeing that expand beyond the standard footprint of the off campus housing community, effectively taking houses permanently off the market for families.”

Lehigh did not respond to a request for comment.

Reynolds said he’ll continue to discuss with Lehigh how they can partner with the city on housing solutions going forward.

“We continue to try to work with Lehigh on partnerships within our neighborhoods, to both have our students be good neighbors and understand that we are all going through a housing crisis together,” said the mayor.

‘A data-driven look’

Confronting a rapidly developing housing crisis—addressing concerns about affordability, displacement, scarcity, and dwindling housing opportunities for long-term residents—is no easy task for a city government. People in Bethlehem care about the issue and want to see change, the mayor said. But stabilizing Bethlehem’s challenging housing market with limited local resources demands complex solutions.

“Passion is not an answer to this problem. It’s passion and sophistication,” the mayor said. “We needed to have a data-driven look at the best uses of our time, our money, and our resources.”

Bethlehem set out on a years-long process to understand its own market. First, in 2017, the city began a blight study with the goal of discovering patterns in any properties that had fallen into disrepair—but only found 29 across the whole city.

Sara Satullo, the Deputy Director of Community and Economic Development for Bethlehem, said the external study of the city’s market was still invaluable. “We got a great snapshot of where the city was,” she said.

Then, shortly after, Bethlehem began to research and engage with the community on a plan to moderate Lehigh’s expansion in the Southside neighborhood. The city’s Department of Community and Economic Development proposed a zoning change that would limit the areas where new student housing could be built, and in late 2020, the council approved the plan.

While a zoning overlay cannot reshape a community overnight, it can regulate what happens in the future. The planning process around the overlay also jump-started the larger housing policy debate that was to come.

Map of student housing rental units in the City of Bethlehem

A map created by the City of Bethlehem which shows the designated student housing areas in orange and the existing student housing units as black dots. Student housing is scattered across the Southside and the city as a whole, though in the future new housing will be confined to the orange areas.

Nearly a year later, the city sent a delegation of elected officials and stakeholders to participate in the Lab’s inaugural Housing Solutions Workshop, which connects teams of local policymakers from small and midsize cities across the country with housing experts at the NYU Furman Center and Abt Associates, to learn how to craft local housing strategies. The Workshop focuses on evidence-based, data-driven strategies cities could implement to address the broad range of challenges that local decision-makers typically face.

“The emphasis was on making sure you have different tools in the toolbox,” said Crampsie Smith, who participated in the program.

Reynolds recalled learning about the long list of policies different cities have employed, and thinking it would be a challenge to hone in on the right policies for Bethlehem.

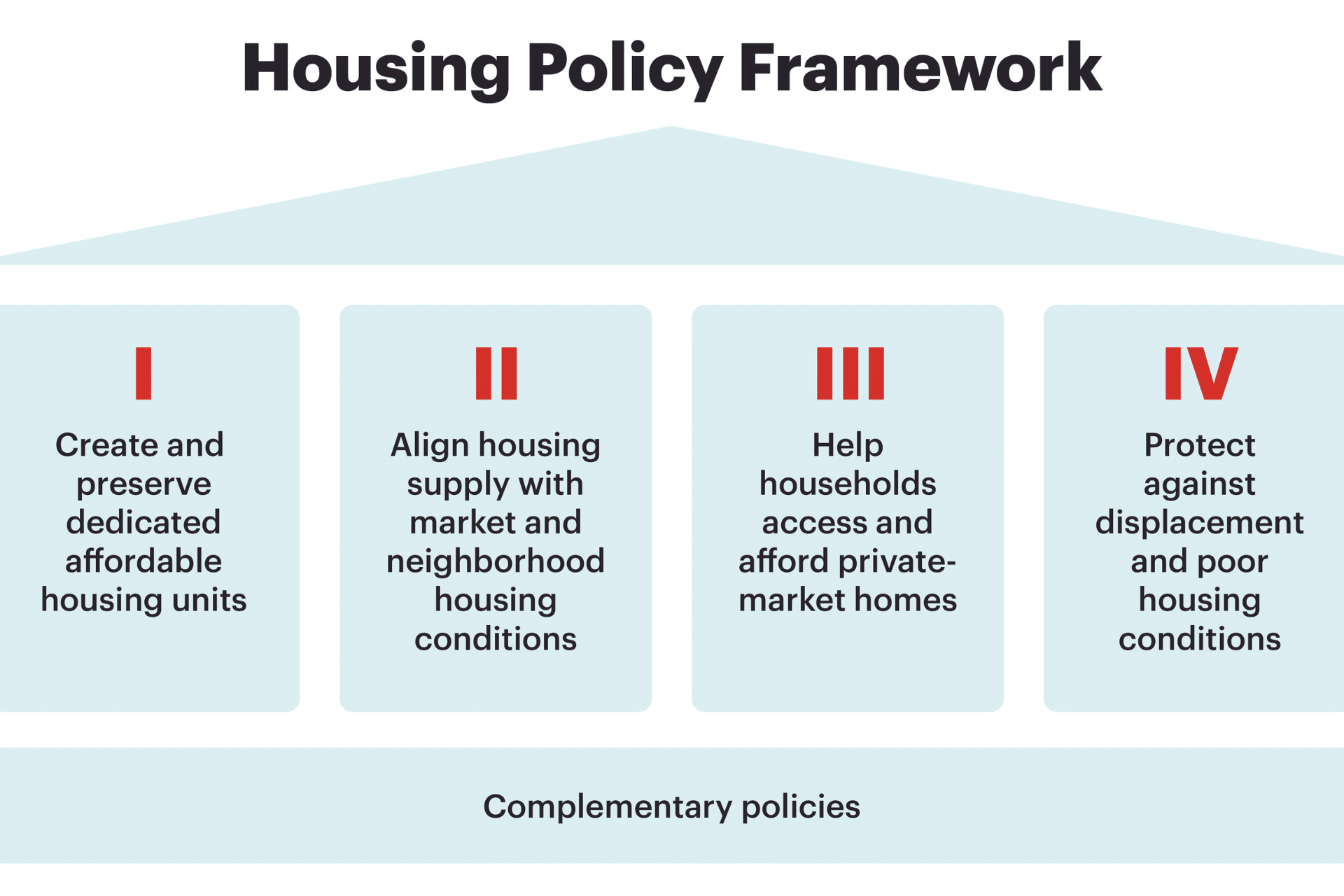

Local Housing Solutions created a housing policy framework to organize and simplify the numerous housing policy options available to local governments.

From there, in January of 2022, the city government issued a request for proposals, searching for a consultant to help analyze the housing market—an analysis that would form the foundation of a new housing plan. Bethlehem consulted with the Lab, which reviewed the prospective bid and provided detailed feedback to the city on what to include to achieve their goals of developing a housing needs assessment.

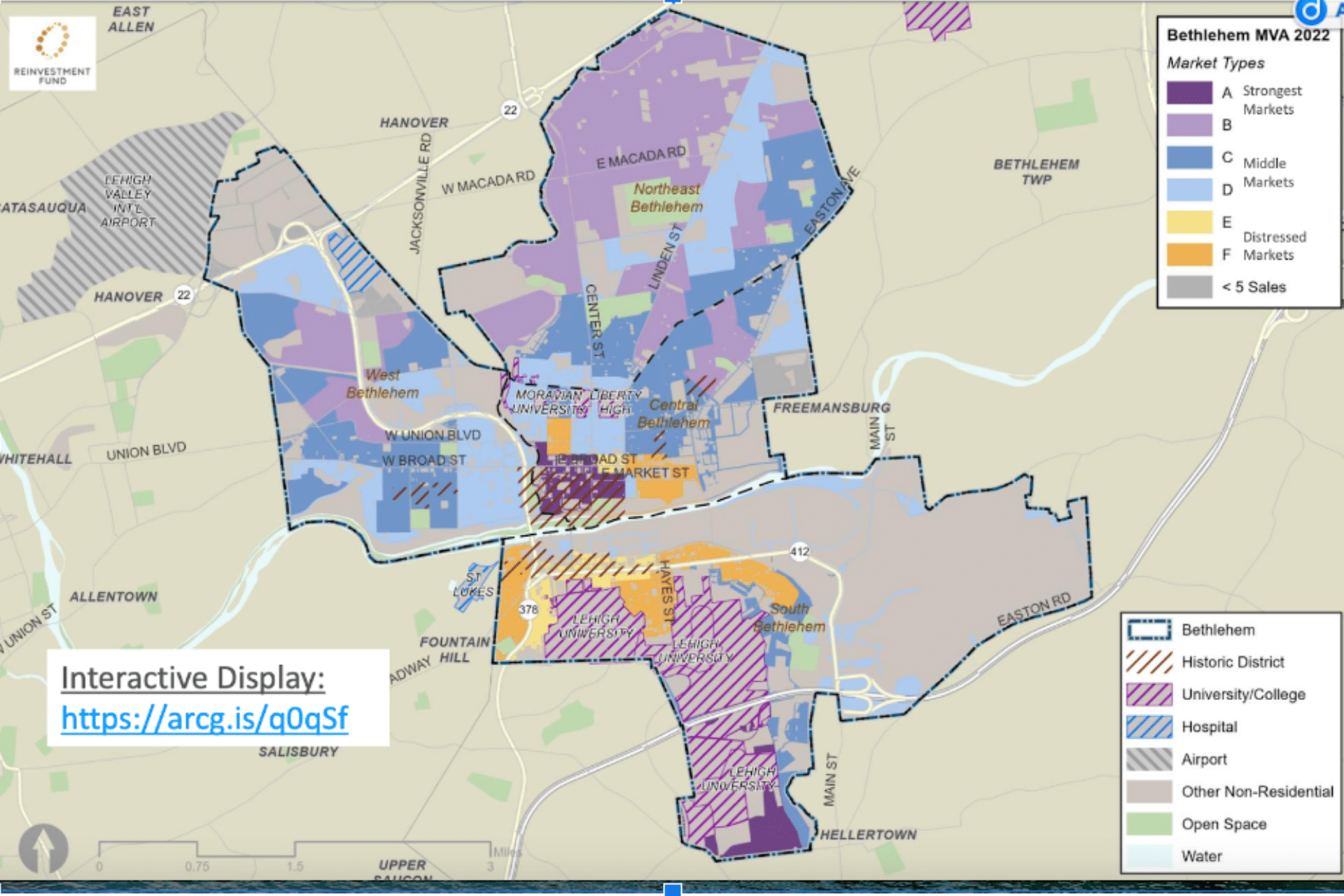

Bethlehem updated market value analysis

A group of three consulting firms—The Reinvestment Fund, Collabo, and Atria Planning—were awarded the project, and conducted a market value analysis showing that rising costs meant very-low and low-income workers could not afford homes in the city.

In 2019, a household making 80 percent of the area median income was able to purchase a home for a family of four in Bethlehem, according to the analysis. By 2022, that was just about out of reach for all households except for those making even 100 percent AMI.

The analysis showed similar affordability challenges for one-bedroom rental units. Breaking down the situation by occupation, the team concluded that it would be “nearly impossible” for a retail worker or a cook to find an affordable apartment in the city. A social worker or paralegal would have a “very challenging” time doing so.

This map from the consultants’ market value analysis shows that Southside Bethlehem has the most distressed markets in the city.

The hired firms also conducted a series of outreach events and a qualitative survey. More than 3,200 Bethlehem residents responded. Thirty-seven percent said they were behind on rent or their mortgage; 24 percent said they didn’t have funding for necessary repairs to their home; 17 percent said they had at least one adult child who was living at home involuntarily because the cost to move out was too high.

“We were really blown away by the response and the level of interest,” Satullo said of the community engagement process. “A lot of people have been waiting a long time to see this plan.”

What’s in the plan?

When the city’s planning committee sat down to finally draw up its plan, the consultants’ housing needs assessment allowed the team to zero in on Bethlehem’s most acute problem: affordable housing for renters. Almost half of the city’s residents rent, and 69 percent of Bethlehem’s cost-burdened households are renters.

The final plan, which was presented to Bethlehem City Council on October 10, includes a range of policies that will be rolled out over the next five years, designed to address this housing goal and others. The plan, detailed below, aims to facilitate new construction, reduce costs for renters, and offer more support for low-income tenants.

It is a carefully constructed, ambitious proposal—but the challenge is that so much is out of the city’s hands, Reynolds said.

Major market factors like inflation and interest rates have significant effects on the housing market. Pennsylvania law limits the amount of power localities have to adopt policies like rent-stabilization or mandatory inclusionary zoning, which are tools that cities in other states like California, Oregon and Washington have at their disposal. Pennsylvania also has an exceptionally high number of government subdivisions—the state has 2,625 municipalities—making regional coordination difficult.

As a local government the city cannot respond as nimbly as it might like to the growing need.

“We know that there’s real pain out there,” Satullo said. “Every day it takes us longer to implement these new housing programs, it’s another person who’s displaced or experiencing homelessness or housing instability.”

‘Not easy to do overnight’

Now begins the hard work of gathering stakeholder buy-in—and implementing the plan.

When the mayor took office in January 2022, his administration set aside $5 million of the city’s American Rescue Plan funding for housing. It spent some of that money on the housing needs assessment, but most of it remains in the city’s coffers.

Even though some funding has already been allocated for housing, and the plan can move ahead without a city council vote, the mayor’s team has been very careful in its presentation of its policies.

“We’re trying to be really accessible and trying to anticipate the points of opposition, and then frame our public communication around answering those concerns, trying to alleviate them,” Satullo said.

Local policymakers have expressed some competing visions of how to tackle the crisis. When Satullo presented the plan, Councilmember Wandalyn Enix said that she wanted to see more focus on homeownership opportunities, while Crampsie Smith worried that hiring so many external consultants was an unnecessary use of funds.

The city has dedicated resources and programs to promoting homeownership, but is now also focusing on providing assistance to renters given the study findings.

The administration has been committed to a methodical, data-driven process, and that can mean things sometimes need to move slower than constituents and legislators may like. Crafting housing policy can be so technical that it can be difficult to explain what is happening and set residents’ expectations.

“The thing that I struggle with the most is: how do you display such a complicated problem in a way that people can understand, without appearing condescending?” Reynolds said.

He says he has found that success stories from elsewhere—which can be accessed through the Lab’s workshop, case studies, and frameworks—are helpful for policymakers when it comes time to persuade skeptical stakeholders on the home front.

"It is extraordinarily valuable to have other conversations with other mayors or other cities to give yourself perspective about how to tackle a problem.”

J. William Reynolds, Bethlehem Mayor

“If we just say we think something is a good idea, there are some people who are going to be like, ‘meh.’ But if we say, ‘Look what worked in Lancaster, Pennsylvania,’ it’s harder for them to say, ‘No,’” Reynolds said. “It is extraordinarily valuable to have other conversations with other mayors or other cities to give yourself perspective about how to tackle a problem.”

Bethlehem has made significant progress and learned important lessons thus far. The city’s problems developed quickly, but they cannot be solved quickly.

“We’re building a framework for how you think about housing,” he said, “which is not easy to do overnight.”