This brief provides a practical guide to local “lead laws” for cities interested in preventing exposure to lead-based paint hazards. It begins with a primer on these ordinances: what they are and how they work. We then provide a brief scan of local lead laws around the country. The third section draws on interviews with practitioners working to implement three recently approved lead laws in Cleveland, OH; Syracuse, NY; and Toledo, OH; to identify key decision points. Finally, we provide individual case summaries on the three sites.

Background

In July 2023, the EPA proposed stronger lead standards to better protect children in older homes and daycares. As a result, when lead paint professionals inspect homes, they now require abatement for homes with any reportable level of lead dust on floors and window sills and will only clear the home if lead levels are below three micrograms on floors and 20 micrograms on window sills post-abatement.

Even with more robust federal standards, preventing lead exposure ultimately depends on cities. Without local action to require and coordinate inspections, federal and state agencies can often only intervene when a child tests positive for elevated blood lead levels (EBLLs)—that is, when a child has already been poisoned by lead.

Preventative action is especially urgent in certain cities and often certain neighborhoods. Rust-belt cities, which combine large shares of housing built before 1978 with high poverty rates, are the most likely to have lead paint hazards. Lead poisoning is also concentrated among children in low-income families of color living in substandard housing, and renters may be especially vulnerable because they rely on their landlords to take action. Research has also shown that targeted lead remediation and prevention in high-risk communities yields large savings in healthcare and special education costs and increases earnings and tax revenue.

What are lead laws?

Lead laws are local ordinances that protect residents from lead-based paint hazards. Some lead laws provide only secondary prevention: they offer guidance on how to address lead paint in the homes of children with EBLLs. Others focus on primary prevention: proactively identifying and remediating lead hazards. These activities fall under localities’ power to adopt housing and building codes requiring housing units to meet minimum standards to protect the health and safety of residents. Localities typically enforce these codes through inspections and citations.

Why have lead laws?

There is no safe level of exposure to lead; even small amounts can cause irreversible cognitive damage. Strong lead laws provide the policy framework to achieve primary prevention. They can target inspections and abatement to the homes that pose the greatest risks, such as pre-1978 properties in poor condition — especially rental properties that can poison many children over time due to resident turnover.1

Within what regulatory context do lead laws operate?

Federal law directs the EPA to regulate lead-based paint hazards, and the EPA does so in a number of ways, including requiring lead-safe work training for those engaged in renovating or repairing pre-1978 homes; requiring specific training for lead paint risk assessors, inspectors, and abatement professionals; requiring sellers and landlords of pre-1978 homes to provide information about lead and lead hazards to potential buyers and renters; and setting standards for dangerous levels of lead in paint and household dust.

Additional rules at the state level often involve testing children’s blood lead levels. For instance, New York State requires lead testing for all children at ages one and two and educational and environmental interventions for lead-poisoned children. The Ohio Department of Health requires testing for children one and two years old who are enrolled in Medicaid, live in a high-risk ZIP Code, or have certain other risk factors. If EBLLs are detected, the department can order lead abatement at the child’s home. The National Conference of State Legislatures tracks lead statutes across all 50 states.

What are the common components of lead laws?

Lead laws commonly create a proactive regime for inspecting and remediating lead-based paint hazards in all or a subset of buildings. They often work in conjunction with a rental registry as a way of identifying properties required to comply and certifying their compliance. A lead law typically:

- Identifies a group of buildings subject to inspection (for example, all pre-1978 residences and childcare facilities, or only rental properties, or only rental properties with a certain number of units). Laws may also prioritize properties in certain neighborhoods for inspection based on historic EBLL or housing conditions data.

- Defines a schedule for inspecting those buildings for lead-based paint hazards. Inspections may occur every few years or at longer intervals if the unit has recently undergone rigorous lead abatement. Events such as tenant requests or complaints, property sales, or unit turnover to a family with a young child could also trigger an inspection. See Benfer et al.’s 2020 study for an in-depth discussion of proactive lead inspections.

- Designates a lead inspection and remediation workforce. Some localities may train their code enforcement staff to conduct lead inspections as part of their normal code inspection regimen. Others require landlords to hire accredited third-party inspectors (sometimes called “lead clearance technicians”). Landlords or private contractors certified for lead-safe repair work or by lead abatement professionals may also carry out remediation work. In all cases, this workforce must adhere to EPA standards for training and certification.

- Sets standards for inspection and mitigation. There are two common forms of inspection: visual assessments and dust sampling. A visual assessment can only identify potential lead hazards such as deteriorating paint, with special attention to areas that receive a lot of traffic (windows, doors, stairs, and porches). Dust sampling involves collecting a dust wipe sample for analysis in a laboratory and can determine the presence of lead particles on surfaces. Aside from inspection, some cities incorporate lead risk assessments, which investigate the locations and severity of hazards and suggest ways to control them; they require a higher level of expertise to conduct. Mitigation can also take different forms, ranging from interim controls (like stabilizing deteriorated paint) to full abatement (such as entirely replacing components like windows and doors).

- Establishes a system to certify buildings as lead-safe and monitor program progress. Localities often award a lead-safe certificate to properties that have successfully passed a lead inspection, and some maintain a public directory of lead-safe rentals. Localities may designate an auditor or evaluator to track compliance and other outcomes.

- Sets penalties for noncompliance. Property owners subject to the law who do not achieve lead-safe status often face fines, which may mount over time. They may also fail to qualify for the rental registry, potentially triggering other consequences, such as being barred from pursuing eviction or receiving rental assistance.

Programmatic initiatives often bolster these legislative elements, including providing grants or loans to landlords and connecting them with vetted contractors, training and certifying lead professionals, and raising community awareness about lead hazards.

How are local lead programs funded?

Local governments can tap into federal funding sources to support their lead remediation activities. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) operates two grant programs to help jurisdictions address lead-based paint hazards through its Healthy Homes initiative. The EPA has historically provided grants to localities for this purpose as well and continues to support them by providing lead contractor training. Meanwhile, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 sent historic amounts of flexible funding to states and localities, which some (including Pittsburgh, PA; and New Jersey) have used to fund their lead laws.

Some state-level programs also pass along federal dollars to municipalities for lead poisoning prevention, including Virginia’s Lead Hazard Reduction program (using HUD funds) and Lead Safe Ohio (using ARPA funds).

Cities can also turn to their health systems and other local stakeholders for support. The Cleveland Clinic contributed $50 million to Cleveland, OH’s Lead Safe Home Fund in 2022, joining the city, the Mt. Sinai Health Care Foundation, United Way of Cleveland, and several local philanthropies in sponsoring lead prevention efforts.

What are some challenges to implementing lead laws?

Lead laws often face opposition from landlords because complying with them may be expensive. The Lead Safe Cleveland Coalition estimates that the cost of a lead inspection is between $250 and $500, and that even interim mitigation measures (distinct from full abatement) can cost as much as $5,000 depending on the property’s condition. A survey and focus groups conducted with landlords in Rochester, NY, however, found that most spent less than $1,000 complying with the new lead law, and some voluntarily made more extensive repairs than required. Financial assistance programs can help address cost concerns.

Resistance can also come from residents with young children who fear that enforcing lead laws will cause landlords to discriminate against them, or those who fear displacement if their household units are deemed unsafe. There is some evidence for both concerns: a 2021 study found that lead laws are associated with fewer families with children living in older housing, probably because of discrimination, and a 2023 paper suggests that lead laws are associated with a higher rate of eviction. More research is needed to analyze these relationships. Although remediation can usually occur while families remain in place, lead hazard control orders require residents to relocate if they cannot access important parts of their home (such as bathrooms and kitchens) for more than a day. Lead complaints could also provoke landlord retaliation in the form of harassment or eviction. The Lead Safe Cleveland Coalition hopes to pilot displacement and emergency housing assistance for tenants affected by the lead law, which creates an important chance to learn more.2

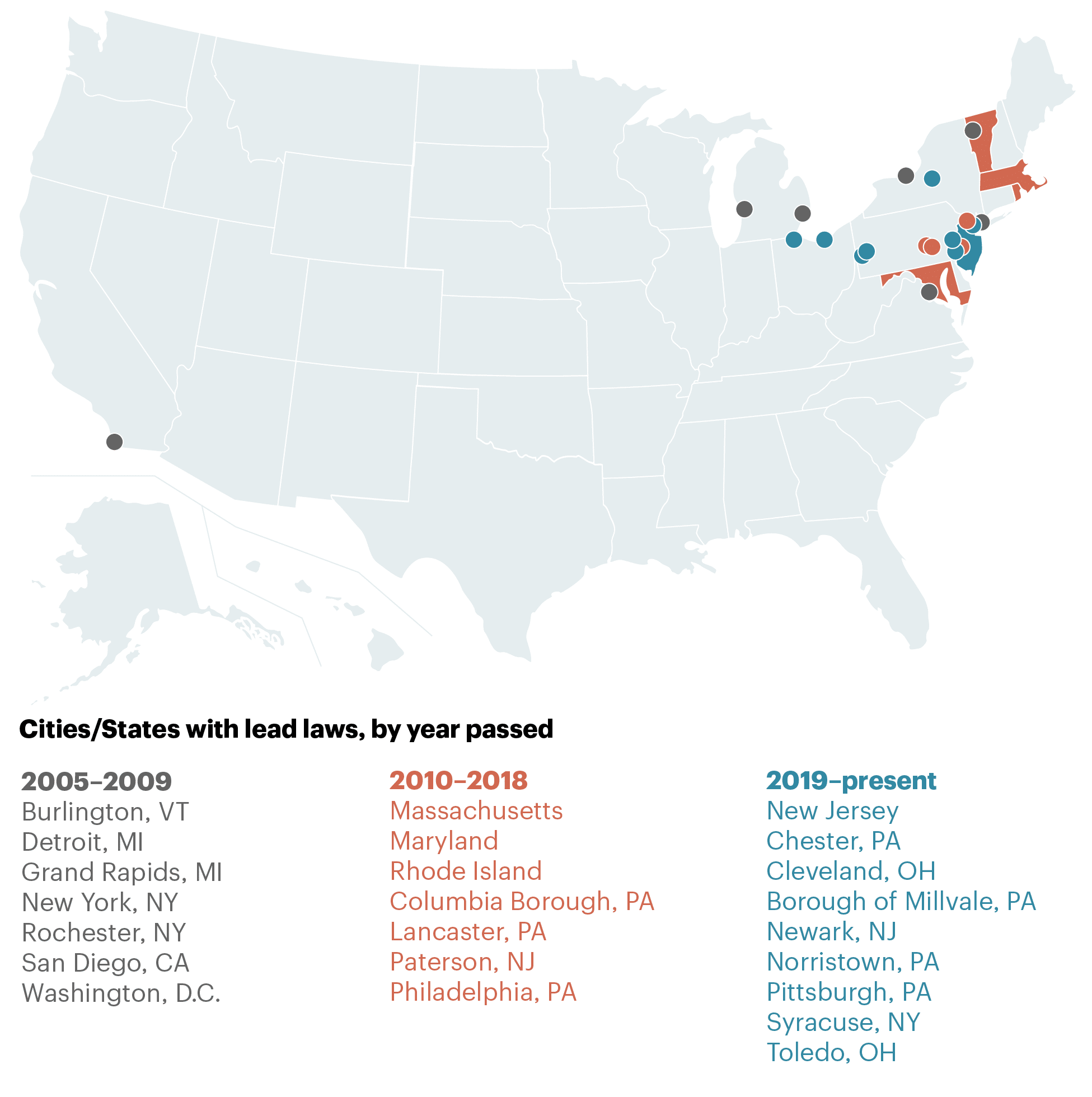

Which cities have lead laws?

Fewer than 20 cities in the U.S. have passed primary prevention lead laws, mainly in the Rust Belt areas across New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Michigan which saw rapid growth during the years when lead paint was dominant (see Figure 1). Katrina Korfmacher and Michael Hanley (2013), and more recently, Emily Benfer and colleagues (2020), provide excellent overviews of these laws. Rochester, NY, passed one of the earliest, and probably best-known lead laws in the country in 2005. It has proven extremely effective, with EBLLs among children in Monroe County (which includes the city of Rochester) falling by 85 percent between 2000 and 2016. Other cities followed Rochester’s lead but varied the type of inspection required; Benfer et al. distinguish between laws that mandate a simple visual assessment, a dust wipe analysis, a risk assessment, and x-ray fluorescence testing. Since Benfer et al. published their scan, several more Pennsylvania cities (Pittsburgh, Norristown, and Chester) have also passed lead laws, and New Jersey passed legislation requiring either visual or dust wipe inspections (depending on the rate of EBLLs among children in the municipality) in pre-1978 rentals statewide beginning in 2022.

Figure 1. Cities and States with Lead Laws as of October 2023

Source: NYU Furman Center Housing Solutions Lab, based in part on Benfer et al. (2020) and Korfmacher et al. (2013).

This brief focuses on three case studies: Cleveland, OH; Syracuse, NY; and Toledo, OH. The cities have similar challenges with housing built before 1978 and adopted primary prevention lead laws around the same time (2019 and 2020, see Table 1). The experience of crafting a lead law is still fresh for these cities, but enough time has elapsed for key differences in implementation to emerge.

Table 1. Lead Laws in Cleveland, Syracuse, and Toledo

Source: NYU Furman Center Housing Solutions Lab interviews and analysis of each city’s ordinance. Rows marked with an asterisk (*) denote U.S. Census Bureau 2021 American Community Survey 1-year estimates.

Designing a lead law: Key decision points for cities

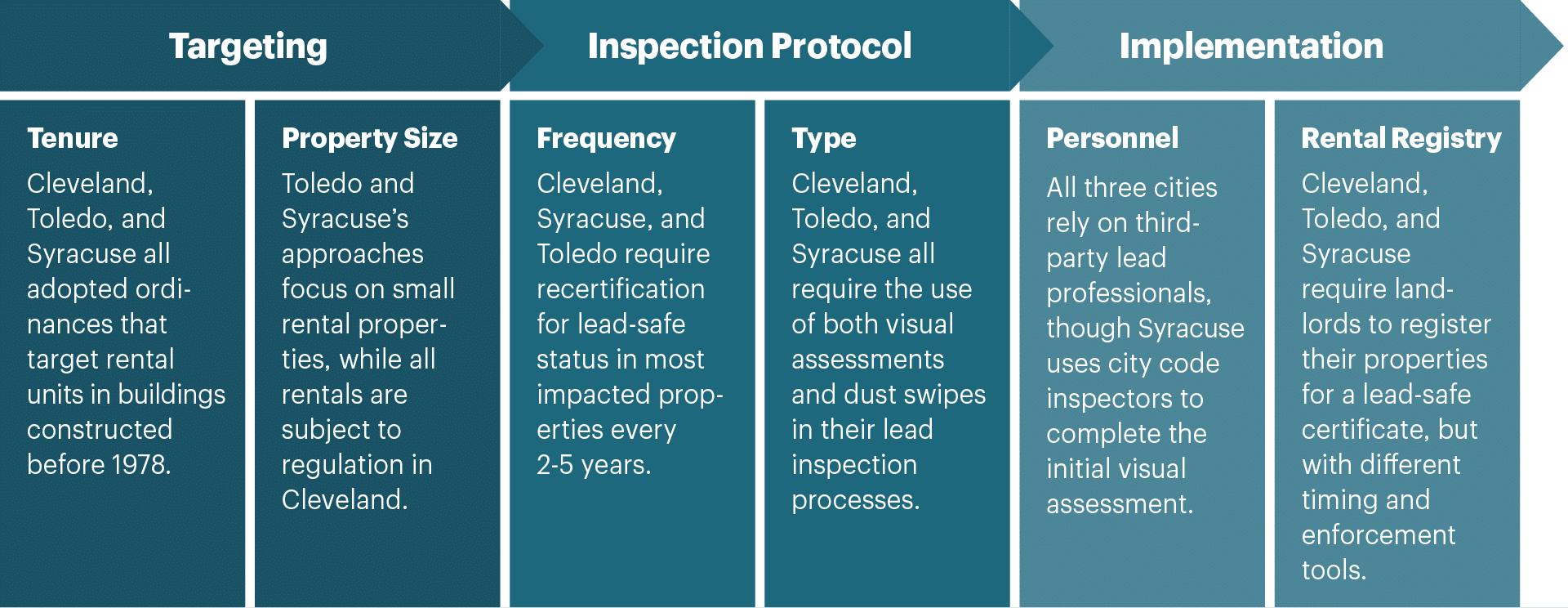

The similarities among the lead laws in Toledo, Cleveland, and Syracuse provide a helpful starting point for cities seeking to establish their own lead laws. At the same time, notable differences illustrate options for cities to consider as they design ordinances to fit their own local contexts.

Figure 2. Summary of Key Decision Points in Lead Law Design

Source: NYU Furman Center Housing Solutions Lab interviews and analysis.

Commonalities

Focus on rental units built before 1978. Cleveland, Toledo, and Syracuse all adopted ordinances that target rental units built before 1978. Research indicates that 97 percent of housing containing lead-based paint hazards was built before 1978. There is also evidence that rentals pose a higher lead-poisoning risk for young children than owner-occupied homes; for example, a Cleveland analysis showed that of 400 properties ordered to address lead hazards between 2014 and 2018, 73 percent were likely rentals.

Mandate inspections every few years. Cleveland, Syracuse, and Toledo require recertification for lead-safe status every two, three, and five years, respectively. An exception is made for properties that pursue full abatement, which are given a longer grace period. Regular recertification is important because these laws permit landlords to use lead mitigation strategies like repainting cracked surfaces. While lead mitigation strategies address lead hazards in the short term and decrease compliance costs compared to full removal, they require consistent monitoring.

Mandate dust swipes alongside visual assessments in the inspection process. Cleveland, Toledo, and Syracuse all require the use of both visual assessments and dust swipes in their lead inspection processes. Visual assessments can detect potential hazards, while dust sampling can determine whether residents are actively exposed to lead while in their homes. Risk assessments and x-ray fluorescence testing can provide an even greater level of detail and accuracy but may be cost-prohibitive for some landlords.

Key Decision Points

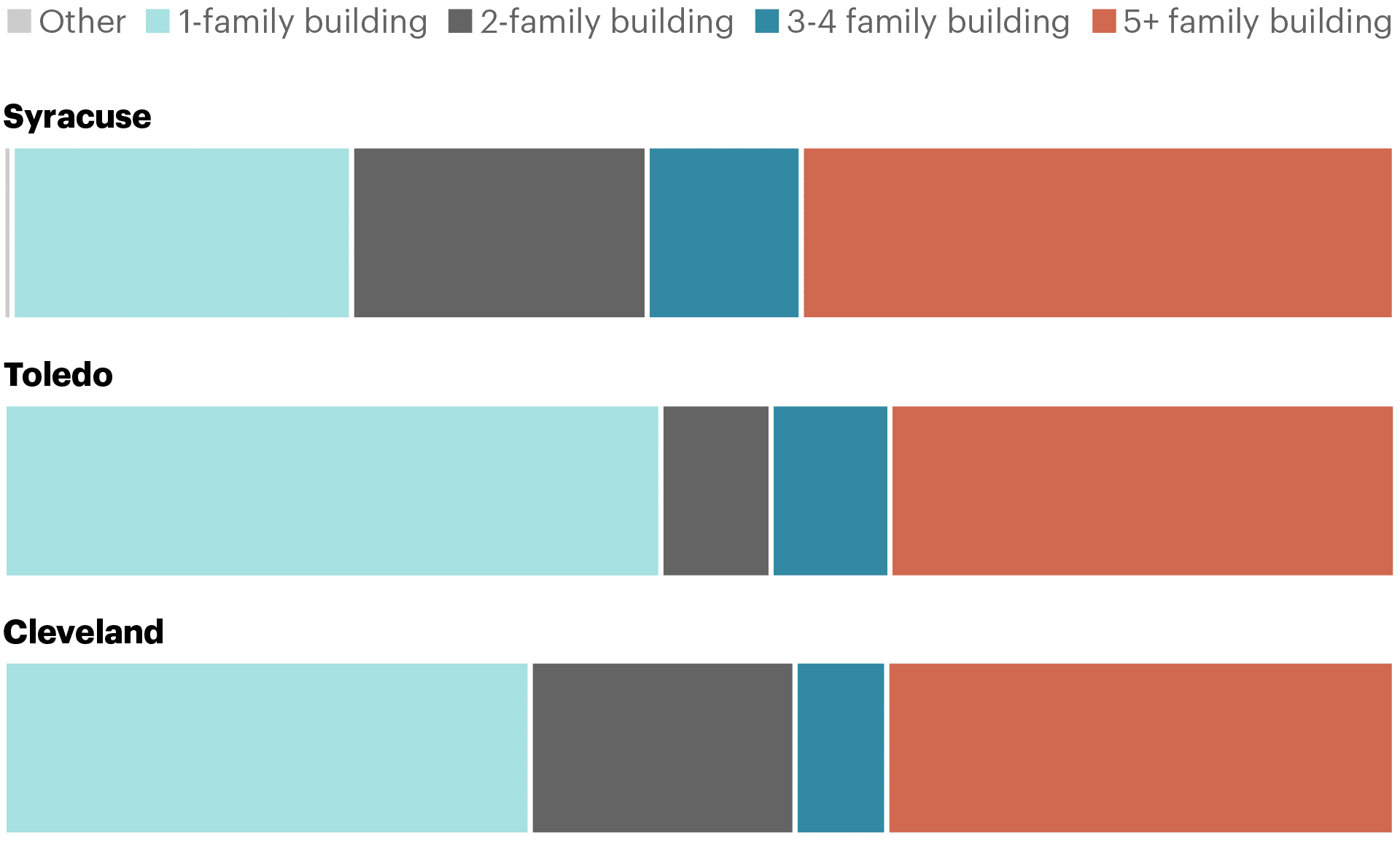

What property sizes should lead laws target? Toledo and Syracuse’s approaches focus on small rental properties (properties with up to four units in Toledo and one- and two-family buildings in Syracuse). In Cleveland, all rentals are subject to regulation, regardless of size. Using property size cutoffs is a way of targeting limited resources to residents at higher risk for lead poisoning, but it comes with tradeoffs. For instance, a Toledo city official reported that children who live in single-family rentals are more likely to have EBLLs.3

Figure 3 below shows that the majority of Toledo renters in pre-1978 buildings live in units subject to the lead law. Still, this leaves the 36 percent of renter households in Toledo that live in properties with five or more units without access to proactive inspections.4 The City Health Dashboard’s “Housing with Potential Lead Risk” metric can be a useful tool in deciding which building types and geographies to target.

Figure 3. Distribution of Renters Living in Pre-1978 Homes by Building Size

Source: U.S. Census Bureau. 2021 American Community Survey 1-year estimates.

Should cities rely on municipal staff or private contractors for lead inspections? All three case study cities rely on third-party professionals during the lead inspection and remediation process. Syracuse opted to utilize city code inspectors to complete the initial visual assessment, however. Training municipal staff to conduct inspections can allow the locality to ensure the integrity of enforcement more directly, but it has drawbacks, too. The Lead Safe Cleveland Coalition “decided against city inspectors because the City lacks capacity, because they wanted to build up the lead-safe industry, and because landlords do not trust [the Department of] Building and Housing. Landlords would deny [city inspectors] access to the unit for a voluntary inspection; they might fear that Building and Housing would cite them for violations unrelated to lead.”5 And indeed, Syracuse program officials reported that property owners refusing to consent to entry has made it difficult to test some units — though they note a tenant’s consent can override the owner’s refusal.6

Even cities relying on independent contractors may need to make significant investments in the lead industry and develop a system for monitoring inspection results. For example, Cleveland maintains a vetted list of lead-safe repair professionals and clearance technicians, offers a free curriculum of classroom and field training to both groups, and is working to access dust wipe results directly from the private lab that tests all dust wipe samples in the city. Syracuse has experienced bottlenecks in its lead grant program because of a lack of independent contractors to remediate hazards. In response, program officials are encouraging professionals in adjacent fields like mold abatement to get lead certified. They are also visiting EPA lead-safe training sessions to spread awareness about the city’s ordinance and ask newly certified technicians to join the city’s list of approved contractors.7

How should lead laws interact with rental registries? Rental registries, which are municipal databases that record information about rental properties and their ownership, are an important tool for enforcing lead law compliance. All three case study cities require landlords to register their properties as part of the application for a lead-safe certificate. In Syracuse, lead inspections and remediation are in fact part of the registration process, which occurs every three years. Currently, the rate of compliance with the rental registry is about 52 percent, so the city must continue identifying properties and owners to fully enforce their lead ordinance.8 Cleveland properties, on the other hand, do not need to be lead-safe certified at the time of their annual application for the rental registry.9 Instead, a landlord’s registration can be revoked if they ever refuse to comply with the lead certification law (and without registration, Cleveland landlords cannot file for an eviction). Cleveland benefits from work conducted at the Center on Poverty and Community Development at Case Western Reserve University to identify likely rental properties not listed in the rental registry.

Case studies

Cleveland, OH

Cleveland is the largest of our three case study cities (see Table 1). It is also the furthest along in implementing its lead law. The Lead Safe Cleveland Coalition was formed in January 2019 to spearhead remediation efforts. The coalition brings together representatives of Environmental Health Watch (which operates the Lead Safe Resource Center as a one-stop shop for tenants and property owners, and for residents interested in becoming certified lead professionals), the Center on Poverty and Community Development at Case Western Reserve University (the official Lead Safe Auditor charged with tracking progress toward lead prevention), and Enterprise Community Partners (which advocates for lead-safe policies at the local, state, and federal level), among others. Since the city adopted its lead law in July 2019, the coalition has worked closely with the City of Cleveland’s Department of Building and Housing to coordinate the six-step process rental property owners must undergo to obtain an official lead-safe certificate.10 The coalition also manages the Lead Safe Home Fund, which gathered over $100 million from multiple sources (including federal stimulus dollars contributed by the City of Cleveland and a donation from the Cleveland Clinic) to provide grants and loans to property owners.

Which buildings does the law target?

Cleveland’s lead ordinance applies to rental properties of all structure sizes, but buildings with five or more units may certify only a share of those units (per HUD testing guidelines).

When is a building subject to inspection?

Inspections (and, if necessary, remediation) occur at intervals of two years. If the owner chooses to pursue full abatement or the testing is conducted with an XRF spectrometer, the City of Cleveland does not require another inspection for 20 years.

In the first three years after adoption, Cleveland gradually rolled out its lead-safe certification process across eight zones, which are delineated based on ZIP codes, in order to give the city time to build up financial assistance, data analysis, and industry capacity. As of March 2023, the Department of Building and Housing has begun enforcing its requirements with penalties.11

What kind of inspection is required?

Cleveland asks property owners to first conduct their own visual assessment and address potential issues before scheduling a formal inspection. Then, the property owner and a certified inspector can jointly choose either to conduct a visual assessment plus a dust wipe or a lead risk assessment. Giving the property owner a role may build trust and reduce the number of expensive inspections they must pay for.

What penalties do property owners face for noncompliance?

Owners may be issued code violations and charged with a first-degree misdemeanor, which can result in a $1,000 fine or six months in jail.

What resources are available for renters and homeowners?

Cleveland stands out for offering incentives and both grants and loans, which nonprofit service providers administer. Property owners must undergo a rigorous application process to qualify, but if they succeed, the entire remediation process is managed on their behalf. The grant and loan products were revamped in September 2023 to make them more generous and increase eligibility.12 Now property owners can qualify for grants of up to $12,000 per unit for up to 12 units or loans of up to $7,500 per unit for any number of units. Rental property owners also receive financial incentives for every unit certified as lead-safe. This larger suite of assistance products may boost compliance, especially among moderate-income property owners.

How does the city monitor and evaluate program progress?

Cleveland’s law designates a Lead Safe Auditor (the Center on Poverty and Community Development at Case Western Reserve University) to analyze and report on lead prevention efforts in the city, including rental registrations, lead certifications, and lead hazard control orders. The Poverty Center maintains a detailed dashboard and produces quarterly reports, which recently began comparing Cleveland to Rochester; Detroit, MI; and others in terms of compliance trends. This analysis suggests that Cleveland needs to see the rate of lead-safe certification applications double to get the city to meaningful compliance with its lead laws within the hoped-for eight years. This kind of information is invaluable for shaping and improving policy going forward.

Syracuse, NY

Syracuse is less than half the size of Cleveland but has equally dire lead challenges. A longstanding program uses grants from HUD and the EPA to support lead remediation efforts in homes with young children, but eligibility rules attached to the funding made it hard for small landlords to participate. Since the city adopted a new lead law in 2020, $4.8 million in ARPA funds have gone towards training and certifying city housing code inspectors in lead testing. The remaining half will provide much more flexible financial assistance to property owners now that inspections have begun.13 Syracuse is unique among the case study cities for using municipal staff rather than contractors to conduct initial lead inspections; their approach has been to “treat [lead hazards] just like another code violation — identify and cite.”14

Which buildings does the law target?

Syracuse’s law technically applies to all residential structures but primarily targets rentals, and specifically one-to-two-unit rental properties, as a byproduct of the rental registry’s structure.

When is a building subject to inspection?

Inspections occur at intervals of three years; tenant complaints can also trigger an inspection. Rather than developing a gradual rollout of the law, the City of Syracuse simply added lead inspections to the existing schedule of housing inspections beginning in August 2022.

What kind of inspection is required?

Units in high-risk areas and small rental properties must undergo both a visual assessment and a dust wipe.

What penalties do property owners face for noncompliance?

The code enforcement division issues fines which, if not paid within one year, culminate in city seizure of the offending property.

What resources are available for renters and homeowners?

Syracuse operates an income-restricted grant program, which recently received more flexible funding to make its grants more accessible.15

How does the city monitor and evaluate program progress?

Syracuse’s law requires the city to publish a public database that documents where lead hazards have been identified and which properties have earned a certificate of compliance, but it is not yet available.

Toledo, OH

Toledo has a larger percentage of single-family homes and a slightly newer housing stock than the other two case study cities. Nevertheless, every single ZIP Code in the city is considered at high risk for lead exposure. The Toledo Lead Poisoning Prevention Coalition, a grassroots group conducting community outreach and advocating for stronger lead safety protections, helped draft the city’s first lead law in 2016.16 The law passed but was later weakened by legal challenges. The city approved an updated version of the law in 2020, but enforcement was again delayed by a lawsuit (the plaintiff, a landlord, argues that the Toledo-Lucas Department of Public Health does not have the authority to enforce the law, since it unfairly targets only certain kinds of residential properties). In the meantime, property owners can still access remediation grants and apply for a lead-safe certificate via Lead Safe Toledo, but on a voluntary basis. If Toledo’s ordinance survives in court, it will stand out as a lead law that is administered by the county’s health department rather than the city’s housing department or code division.

Which buildings does the law target?

Toledo’s law targets one-to-four-unit rental properties and owner-occupied homes with in-home daycares.

When is a building subject to inspection?

Inspections occur at intervals of three years. If the owner chooses to pursue full abatement, Toledo does not require another inspection for 20 years. The city plans to phase in enforcement over the course of five years, prioritizing the census tracts at the highest risk for lead poisoning.

What kind of inspection is required?

A visual assessment and dust wipe is required for all properties covered by the law.

What penalties do property owners face for noncompliance?

Toledo threatens fines of up to $10,000 per year per dwelling unit, depending on how long the owner has been out of compliance.

What resources are available for renters and homeowners?

Toledo provides grants to low-income homeowners and owners of affordable rental properties. It also offers an “early bird matching grant,” which reimburses up to 50 percent of the cost of remediation for the owners of low-income rental properties who comply within the law’s five-year phase-in period.

How does the city monitor and evaluate program progress?

The Toledo-Lucas County Health Department will prepare an annual report for the mayor and city council that includes the number of applications for a lead-safe certificate and the number of properties not compliant with the lead law.

Conclusion

The lead laws recently adopted in Cleveland, OH; Syracuse, NY; and Toledo, OH, present an opportunity to understand the different approaches cities can take to prevent lead exposure and begin to explore the advantages and challenges of each approach. It is too soon to evaluate the impact of these laws, though future research should investigate a range of outcomes, including the rate of lead poisoning based on child blood lead levels, the number and share of lead-safe housing units, the incidence of eviction and displacement among tenants, and the cost of compliance for landlords.

Footnotes

- Smith, Monica. (2023, May 4). Lead Safe Coordinator, City of Toledo. Personal interview. ↑

- Blue Donald, Ayonna. (2023, May 1). Enterprise Community Partners, Vice President, Ohio Market. Personal Interview.↑

- Smith, Monica. (2023, May 4). Lead Safe Coordinator, City of Toledo. Personal interview.↑

- Analysis of U.S. Census Bureau 2021 American Community Survey 1-year estimates.↑

- Blue Donald, Ayonna. (2023, May 1). Enterprise Community Partners, Vice President, Ohio Market. Personal Interview.↑

- Vinciguerra, Jessica and Keenan Lewis. (2023, May 3). City of Syracuse. Personal interview.↑

- Vinciguerra, Jessica and Keenan Lewis. (2023, May 3). City of Syracuse. Personal interview.↑

- Vinciguerra, Jessica and Keenan Lewis. (2023, May 3). City of Syracuse. Personal interview. ↑

- Fischer, Robert. (2023, April 14). Associate Professor, Case Western Reserve University. Personal interview.↑

- Blue Donald, Ayonna and Wyonette Cheairs. (2023, May 1). Enterprise Community Partners. Personal Interview.↑

- Blue Donald, Ayonna. (2023, May 1). Enterprise Community Partners, Vice President, Ohio Market. Personal Interview.↑

- Blue Donald, Ayonna. (2023, May 1). Enterprise Community Partners, Vice President, Ohio Market. Personal Interview.↑

- Vinciguerra, Jessica. (2023, May 3). Lead Grant Program Administrator, City of Syracuse. Personal interview.↑

- Lewis, Keenan. (2023, May 3). Lead Program Administrator, City of Syracuse. Personal interview. ↑

- Vinciguerra, Jessica. (2023, May 3). Lead Grant Program Administrator, City of Syracuse. Personal interview.↑

- Wood, Marilynne. (2023, May 3). Professor and Researcher, University of Toledo; Member, Toledo Lead Poisoning Prevention Coalition. Personal interview.↑