J.R. Reed

November 23, 2021

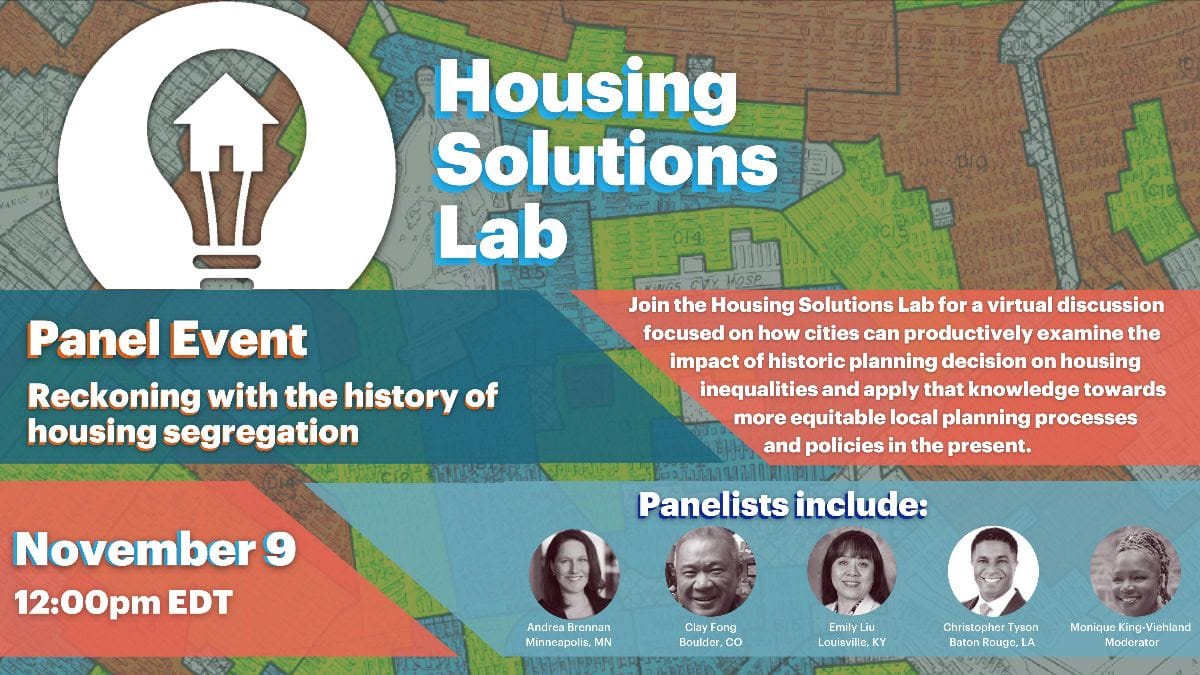

On November 9, we hosted a virtual panel discussion on how to advance equity in local housing planning, featuring community leaders from Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Boulder, Colorado; Louisville, Kentucky; and Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Exclusionary and discriminatory housing policies have shaped America’s cities for decades and foster inequalities in housing that persist to this day. Leaning on the experiences in their respective cities, these leaders shared insights on how cities can learn from their past planning mistakes to promote a more equitable future.

While these cities all face idiosyncratic housing challenges, the panelists agreed that significant public engagement and a deep understanding of their community’s history are prerequisites to developing equitable policies today.

Minneapolis has been lauded in recent years for a comprehensive plan approved in 2018 to end single-family zoning. Andrea Brennan, the city’s Director of Community Planning and Economic Development, emphasized that Minneapolis did not set out to do so, but rather it was the product of extensive conversations with communities. That included supplying residents with relevant historical data and visualizations, including the Mapping Prejudice project – a map that tracked the racially restrictive covenants recorded against single-family homes in Minneapolis.

“A big part of this was addressing our racist past in zoning, but it was also about expanding choice and opportunity in every neighborhood of our city,” Brennan said. “What we heard very loud and clear is that folks want more housing opportunities…You can’t get at that diversity and increase affordability without looking at the single-family-home zoning requirement and considering relaxing it.”

Similarly, Louisville launched a zoning reform effort in the summer of 2020, but that work started with a comprehensive plan five years ago that featured expansive public engagement, particularly to communities of color in the city’s West End. City officials facilitated meetings with residents, but also lawmakers and planners, about the specific land use policies that segregated the city.

According to Emily Liu, Director of Louisville’s Metro Planning and Design Services, the city is still very segregated, with a significant family wealth gap between Black and white households. And, prior to the reform, 75% of land in the city was zoned for single families. Liu said that confronting the city’s history allowed it to remedy decades of disinvestment in and layers of restrictions on communities of color.

Deep Understanding of Community History

The panelists underscored how critical it is for local officials to “anchor” in their particular histories and bring intentionality to reversing these legacies of systemic racism. From Minneapolis to Louisville to Baton Rouge to Boulder, specific historical decisions explicitly resulted in racial segregation and adversely impacted wealth distribution and resource allocation.

“These are the intentional results of specific policies made in a conscious effort to achieve certain goals,” Chris Tyson, president and CEO of the redevelopment authority Build Baton Rouge, said. “None of it is accidental. There is no ‘urban crisis’…when we begin there, we understand the massive level of public resources, political will, and public policy that were organized around the racialized development of urban space in all of these locales.”

By understanding the scale and aggregation of those decisions over decades and then recognizing the lack of reparative work to rectify those wrongs, residents can better contextualize the ongoing racial stratification in certain cities.

In Boulder’s case, residents have long been opposed to high density in favor of open space, according to Clay Fong, community relations manager in the city’s Office of Human Rights. But, Boulder’s pride in and embrace of environmental justice runs counter to ordinances that have had detrimental exclusionary impacts. Absent explicit interventions to reverse these policies, Boulder and cities across the U.S. can’t chart a more equitable path forward.

Paths Forward

How then should we plan for these cities and communities impacted by discriminatory housing policies?

Panelists highlighted seven potential steps:

- Regulate markets by prioritizing affordable housing, particularly in gentrifying areas with high demand for land and low supply.

- Professionalize community development work to increase capacities for communities to lead.

- Target missing ‘middle housing’ through zoning changes by increasing investment and supporting developers who are building duplexes and triplexes in this space.

- Create pathways for emerging developers of color to benefit from community partnerships.

- Direct the benefits of new investments dollars to those who have been displaced from certain neighborhoods, particularly in cultural corridors.

- Enact inclusionary zoning to ensure developers set aside a percentage of housing units at below market rates.

- Partner with research organizations to measure the effectiveness of new housing policies.

To take these steps and address historical ills, the panelists also emphasized the need to foster an entire “ecosystem” of support, from community development financial institutions, to large banks, to state entities, and grassroots organizations.

“Zoning alone is not a fix,” Brennan said. “It’s necessary but not sufficient without policy and investments that are very targeted in achieving [specific community] goals.”

For more, check out tools from these cities, including a story map built through Louisville’s zoning reform effort, as well as a report on strategies for affordable housing in Minneapolis. And, read Chris Tyson’s article examining the impact of municipal fiscal crisis on equitable development in the Fordham Law Journal.

To further explore the housing needs of the cities featured on the panel, and even more across the U.S., check out our Housing Needs Assessment Tool.

One Response