On this page

Developing an anti-displacement strategy

Overview

Rising rents or property taxes can make it difficult or impossible for families to afford to remain in their homes. In many instances, displaced residents and businesses struggle to find comparably affordable, transit-connected locations for relocation. The resulting housing instability and insecurity can adversely impact their overall well-being.

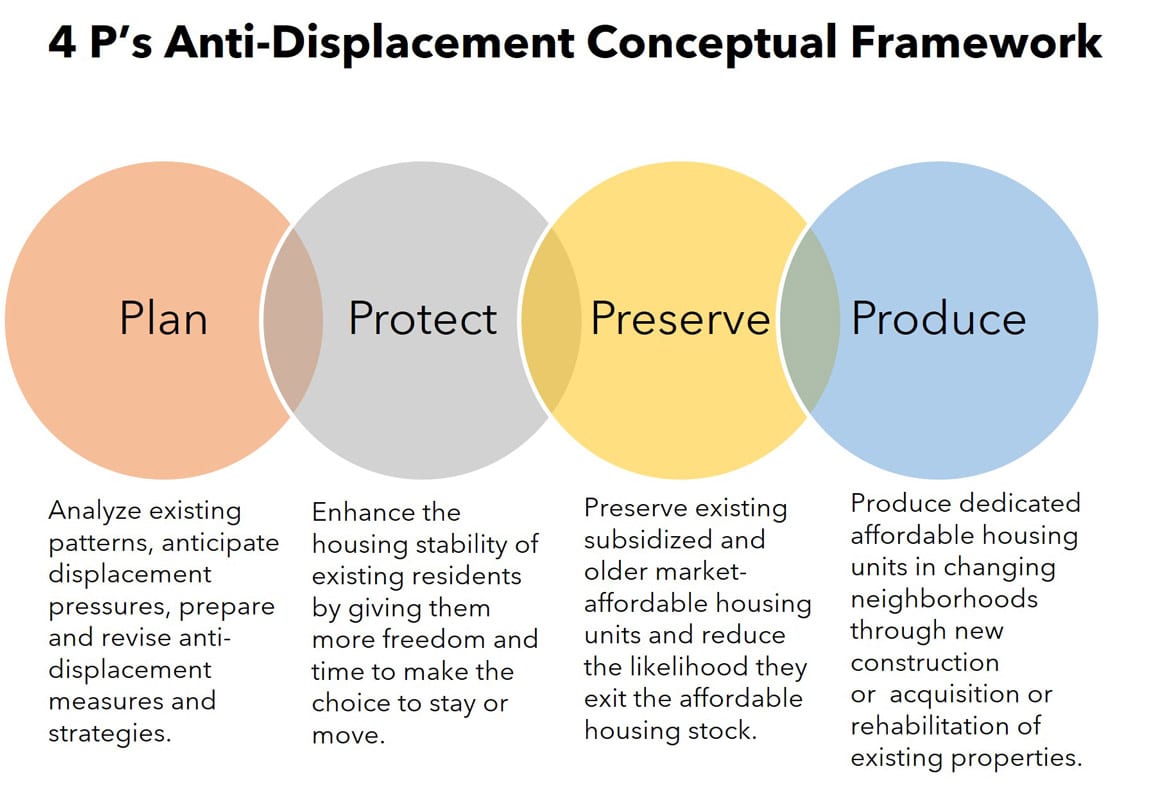

This brief provides guidance on how localities can develop an anti-displacement strategy in neighborhoods experiencing rising rents and home prices. This includes preserving housing opportunities for low- and moderate-income households and preventing displacement among existing residents who struggle to afford the higher housing costs. We propose four main categories of an anti-displacement strategy:

- Plan ahead to identify the neighborhoods (or other areas) where action may be needed to preserve affordable housing opportunities for low- and moderate-income households

- Protect long-term residents from the adverse effects of rising rents and home prices

- Preserve existing affordable housing

- Produce additional dedicated affordable housing for low- and moderate-income households

Our framework adds a fourth P (to denote Plan), to the widely used 3P’s (Protect, Preserve, and Produce).1 The Plan category facilitates a proactive approach to preparing an anti-displacement strategy that intervenes early in the cycle of housing cost increases.

For each category, we propose the objectives localities could pursue and list some possible steps and housing policy options to achieve these objectives.

Other types of displacement are not covered in this brief. For example, we address actions to help individual households avoid eviction and foreclosure elsewhere on Local Housing Solutions.

Why develop an anti-displacement strategy?

A key goal of an anti-displacement strategy is to maximize existing residents’ choices about when, whether and under what circumstances to move, preserving families’ ability to stay in their homes and neighborhoods if they wish to do so. By creating an anti-displacement strategy, localities can ensure that they have the necessary tools and systems in place to anticipate and respond to displacement pressures from rising rents and home prices in a timely manner. An anti-displacement strategy provides public officials and staff, practitioners, and advocates with a roadmap to ensure residents have more control over decisions to move from or remain in a neighborhood experiencing rising housing costs. By preserving and expanding the availability of affordable housing, an anti-displacement strategy can also help ensure that other low- and moderate-income households can find housing in affected neighborhoods.

Description

As shown in the diagram, an anti-displacement strategy is a multi-pronged effort that plans ahead to anticipate where rising rents and home prices may jeopardize the ability of low- and moderate-income households to afford to live there, protects long-term residents, preserves existing affordable housing, and produces additional dedicated affordable housing for low- and moderate-income households.

The following sections outline the main objectives and the possible policy options for each of the four categories. Within each section, readers have the option of reading a summary version or expanding to see additional content.

Plan

Objectives

- Analyze existing urban growth patterns, neighborhood composition, and infrastructure needs.

- Recognize the changing trends, assess the proposed investments, and anticipate the growing real estate demands and resulting displacement pressures.

- Prepare, fund, monitor, and revise appropriate measures and strategies.

Many localities are using a diverse array of policy options to address displacement stemming from rising housing costs. In many cases, however, these steps are taken in reaction to sharply rising rents and home prices rather than in anticipation of these trends, increasing the cost and reducing the effectiveness of these efforts. To facilitate a more proactive approach that intervenes earlier in the cycle of housing cost increases, we focus here on the vital steps of (a) planning ahead to anticipate areas in need of policy intervention and (b) developing a formal anti-displacement strategy to provide the policy tools needed to act quickly to help preserve existing affordable housing, protect existing residents, and produce new dedicated affordable housing in targeted neighborhoods.

The initial planning process to inform the development of an anti-displacement strategy provides an opportunity to take stock of the types and intensity of the housing cost pressures in different areas of the locality and develop a toolkit that can be deployed in response to those pressures. Understanding neighborhoods at risk and their residents’ differing needs is critical to tailoring and combining effective policy options.

Once an anti-displacement strategy has been adopted, ongoing planning will become a component of that strategy.

Steps

One of the primary steps involved in preparing an anti-displacement strategy is to identify neighborhoods experiencing or at risk of experiencing rising rents and home prices and other displacement risk factors in the short-, medium-, and long-term. Localities can conduct a detailed neighborhood analysis to identify at-risk neighborhoods in close consultation with the community and with the help of trusted community partners. Two main components of this analysis are trends analysis and investment-risk analysis.

- Trends analysis: To identify neighborhood-level trends, localities can supplement their housing needs assessment with detailed data on residential sales and rents or conduct tailored surveys to predict trends in rents and home prices. Tracking evictions and rents are the most simple and effective means for predicting this type of displacement.

- Investment risk analysis: This involves assessing the impact of proposed projects and large-scale investments, both public and private, on at-risk neighborhoods to devise protective measures. Investment examples include: parks, public transit investments, stadiums, etc.

Optimally, localities will formalize their planning efforts in an anti-displacement strategy that includes:

- an ongoing process for regularly updating an assessment of the neighborhoods/areas where preservation/anti-displacement efforts are needed

- a description of the steps that will be taken to conduct neighborhood-level planning and community consultation in these neighborhoods to better understand residents’ preferences, and

- a list of specific policy tools that will be put in place to protect residents from displacement, preserve existing affordable housing and produce new affordable housing in those neighborhoods. While some of the policies may require city-wide implementation, most will focus on the target neighborhoods identified through ongoing assessment and analysis.

Once localities have formalized an anti-displacement strategy, they will benefit from establishing a clear monitoring and implementation framework for it along with steps to ensure dedicated funding for anti-displacement efforts through available funding resources.

This section describes a sequential series of steps leading up to the adoption and implementation of an anti-displacement strategy. Planning elements should also be incorporated into the strategy to ensure the locality regularly refreshes its map of areas experiencing or at risk of this type of displacement.

- Community consultation: Localities will benefit from community outreach and consultation to better understand the perspectives, concerns, and priorities of residents. Localities limited by resources or time to undertake a detailed consultation process may identify issues by synthesizing any existing task force or community coalition recommendations to prevent displacement. Conducting public outreach and consultation by partnering with trusted local community groups and organizations before beginning a detailed technical analysis can help localities identify specific local patterns, community concerns, and high-priority neighborhoods. Community consultation and technical analysis can reinforce each other as an iterative process that can inform the data collection points and methodologies to analyze and map displacement pressures.

- Conduct a trends analysis to identify at-risk neighborhoods: Sharp increases in property values and rents, housing sale listing activity, and rate of evictions and foreclosures can help localities identify neighborhoods where there is a need for efforts to preserve and produce affordable housing and protect residents from displacement. However, it is important to try to anticipate where housing demand is starting to rise and is expected to rise further in the future so that localities can target those neighborhoods for a proactive policy response. Many localities already conduct neighborhood analysis and have developed a housing needs assessment that can be a helpful initial step toward gathering the data needed for this analysis. (While it will be important to supplement these data with local data, Local Housing Solutions’ Housing Needs Assessment Tool provides access to data on housing conditions for localities throughout the U.S.). Localities can also buy data from private agencies and vendors on real estate sales, demand trends, and recent and current rents.

Places like San Francisco, Portland, and Chicago, among others, have devised “Neighborhood Early Warning Systems” to identify neighborhoods that may be expected to experience increases in rents and housing prices. Some data elements that may signal likely rent increases related to increasing construction activity and economic investments are building permit and zoning variance requests, new retail permits for niche businesses such as coffee shops and ice cream parlors, and shifts in the racial and other demographic characteristics of the neighborhood. While these types of predictive models are not always completely accurate, they may help localities get ahead of the curve and undertake place-based policy measures before housing costs rise to the level where they are untenable for low-and moderate-income households. It is also much more expensive for localities to acquire land and implement other housing solutions once prices increase substantially.

Some localities are obtaining more fine-grained information on displacement through surveys and private datasets. For example, Missoula, Montana, used an online survey on housing displacement, and Puget Sound Regional Council introduced a question on housing displacement in their household travel survey.

- Anticipate change and coordinate public and private investments: Large-scale infrastructure investments and economic initiatives can have a sizable impact on the housing cost and displacement pressures of affected neighborhoods. Localities will want to assess the impact of proposed projects and public investments on existing predictions of at-risk neighborhoods. Incorporating growth objectives and infrastructure investments into forecasting models and planning for different scenarios may help localities to prepare for unintended consequences like rent and home price increases and resulting displacement. This can allow localities to anticipate the potential for adverse impacts due to public and private interventions in or near communities vulnerable to displacement and build necessary protections into proposed plans and investments to mitigate this risk and adverse impact. This transparency will also help affected communities mobilize together to collaborate with the government and private actors in decision-making processes to prioritize their well-being. Localities may wish to consider incorporating such assessments and protective measures as a standard process for infrastructure and capital investment planning.

- Prepare an anti-displacement strategy: To ensure localities are prepared to address the challenges faced by residents of neighborhoods experiencing rent and home price increases, it’s important to develop a policy toolkit and formalize it as part of an anti-displacement strategy. This brief includes recommendations for specific policies to consider in later sections, but generally, the policies included in the strategy should strive to maximize opportunities for existing residents of neighborhoods experiencing rent and home price increases to stay in their homes. By preserving existing affordable housing and producing new affordable housing, an anti-displacement strategy will also preserve and expand opportunities for low- and moderate-income households to move into these neighborhoods. Anti-displacement strategies generally also include steps to help residents in instances where displacement might eventually occur despite the adoption and implementation of proactive protective measures.

Localities will want to select appropriate policy tools for their community based on the locality’s overarching anti-displacement goals, identified community needs, effectiveness and cost of different policy options, and their own local capacities and resources necessary to adequately develop and implement these tools. (See an example of policy prioritization assessment from the University of Texas, Austin). In addition to deploying new tools, an anti-displacement strategy can provide opportunities for localities to consolidate existing policy efforts and revise them to incorporate anti-displacement priorities in coordination with their local housing strategy and comprehensive strategic vision.

Some of the policies included in an anti-displacement strategy document will require broad implementation across the locality. But often, the policy options will focus on targeted policies that direct housing resources toward certain qualifying neighborhoods or a contiguous geographic region like downtown areas based on objective metrics and neighborhood analysis.

To help inform the preparation of an effective anti-displacement strategy, it will be important to undertake an in-depth neighborhood-level planning and community consultation process with local leaders (political and faith-based), community organizations, resident welfare associations, tenant organizing groups, small-business owners, and other community groups. A neighborhood approach to anti-displacement allows targeted groups within these neighborhoods – tenants, small-scale property owners, legacy homeowners – to opt-in and prioritize their needs and become partners in the process (See the Equity Lab’s interactive activity to engage the community in devising anti-displacement strategies.)

- Fund, implement, and monitor: Implementing anti-displacement measures requires steady and reliable sources of funding and continued community and political support. In addition to generating new sources of funding to implement the strategy, localities can also dedicate a percentage of local housing funding resources generated through general obligation bonds, tax increment financing, linkage and impact fees, among others.

Political support is critical for the effective coordination and implementation of an anti-displacement strategy. An involved elected leadership can facilitate interdepartmental coordination and build community trust in the local government’s commitment to housing displacement concerns. Localities implementing anti-displacement strategies often encounter political challenges when they need to target funds to particular neighborhoods. Having a clear and transparent process for prioritizing funding as well as alternative programs to offer other neighborhoods can be helpful in ensuring broader political support. Finally, to stay relevant and effective, even the most well-designed anti-displacement strategy will need revisions and adjustments to reflect the changing circumstances of the housing market, community priorities, and local economy. Regular evaluation and monitoring through carefully designed metrics, review mechanisms, and community consultation can alert localities to when changes are needed to improve the strategy’s performance.

Protect

Objectives

- Enhance the housing stability of renters and homeowners subject to increased economic burden from rising housing costs. This means giving existing residents more freedom to decide whether and under what circumstances to move out of their homes and neighborhood.

- Allow existing residents to benefit from improved infrastructure and amenities in their neighborhoods.

- Help residents transition into new homes in their existing neighborhood or another neighborhood of choice when they are displaced.

Long-term residents of neighborhoods with rising rents and home prices are at heightened risk of being priced-out of their homes and neighborhoods. An anti-displacement strategy should protect these residents and give them more time and ability to choose whether they want to move and under what circumstances. When residents prefer to stay in their existing homes, policies can offer financial and technical assistance to allow them to stay and benefit from improved access to high-quality amenities and infrastructure. In the instances where residents are forced to move, policies can support their transition into new homes – either in the existing neighborhood or in a neighborhood of their choice.

To be clear, the protections available in most localities generally do not provide long-term or full-proof protection. Policies can provide residents greater control over their moves, allowing renters time to arrange their moves and homeowners an opportunity to stay in their homes as values rise without being forced to sell due to property tax increases. In some cases, especially where localities use the “bought time” to develop dedicated affordable housing, they can create opportunities for long-time residents to shift into such housing, allowing them to stay in the same neighborhood.

Steps for renter protection

Anti-displacement strategies often include policies that help protect renters from being forced to move. These protections can be in the form of regulating property renting practices, bolstering tenant rights, and providing financial and legal assistance to tenants. Key categories of assistance include:

- Regulating property rents: When the demand for housing increases in a particular neighborhood, property owners may increase rents substantially, forcing tenants to either move on their own or default on rent payments, which may, in turn, result in evictions. Rent stabilization policies set limits on rent increases to stop rents from rising too quickly. They may also include some procedural protections, like requiring property owners to offer relocation assistance to tenants in certain cases to help with the transition.

- Bolstering tenant rights: Some property owners upgrade the units in their developments, redevelop rental buildings into condominiums or sell the building to be demolished and redeveloped. To help protect residents in these circumstances, localities can introduce procedural protections such as just cause eviction policies to discourage aggressive property owner action against tenants. They can also make accommodations for renters to stay in their building through right-to-lease policies. At a minimum, localities can slow the process of clearing residents when a property owner proposes to reposition a property for higher-income households by instituting right of first refusal policies.

- Financial assistance to tenants: Localities may offer financial assistance to renters to provide housing stability with the help of tenant-based rental assistance programs and offer homebuying assistance programs to overcome credit and down payment barriers and help build wealth for long-term financial security.

- Legal assistance to tenants: Localities can partner with community groups and legal aid clinics to equip renters with information and legal assistance to fight eviction orders and property owner negligence and force owners to maintain the building and premises in good physical condition.

Rapidly rising rents can put existing renters at significant risk of displacement. When demand for housing increases in a particular neighborhood, property owners may increase rents substantially, forcing tenants to either move on their own or default on rent payments, which may, in turn, result in evictions. In some cases, property owners may also allow units to degrade without adequate maintenance in order to indirectly force tenants to move. Property owners may upgrade the units in their developments, redevelop rental buildings into condominiums or sell the building to be demolished and redeveloped. Such actions can raise rents considerably, making it prohibitive for low-income residents to continue to stay in the same location.

The following are some key steps to protect renters:

- Rent stabilization policies can set limits on rent increases to stop rents from rising too quickly. They may also include some procedural protections like requiring property owners to offer relocation assistance to tenants in certain cases where they may be allowed to increase rents above the stated limits, such as after capital improvements. Localities that do not have rent stabilization policies, or cannot have such policies due to state preemptions, can still offer other procedural protections to provide renters more stability.

- Procedural protections can discourage aggressive property owner action against tenants, make accommodations for renters to stay in their building, or at a minimum slow the process of clearing residents when a property owner proposes to reposition a property for higher-income households. Some procedural protections include:

- Just cause eviction policies limit the circumstances in which property owners may evict tenants to a series of prescribed circumstances, such as non-payment of rent and intentional damage to the property and provide funding for penalties for property owners who fail to comply with the requirements.

- Right-to-lease renewals often accompany just cause eviction policies and allow tenants the right to renew their leases when the property owner cannot show any legally recognized basis for eviction.

- Right of first refusal policies protect tenants by facilitating the safe transfer of property to the tenants, tenant association, or other approved mission-oriented buyers when the owner of a rental property chooses to sell the property or convert it into a condominium. To be effective, such policies generally require a substantial amount of technical and financial assistance for tenant associations or strong partnerships with established nonprofits with housing expertise.

- Legal assistance: Neighborhoods experiencing rising rents often experience increased rates of eviction, even in localities where policy protections are in place. In such instances, localities can partner with community groups and legal aid clinics to equip renters with information and legal assistance to fight eviction orders.

- Financial assistance: Localities may offer financial assistance to renters directly or indirectly to provide them with housing stability, increased opportunity, and long-term financial security. Many localities dedicate a certain portion of their Housing Trust Funds toward rental assistance programs.

- Tenant-based rental assistance programs provide renters with help affording the rents of units they locate on their own. In addition to federally funded Housing Choice Vouchers, which have no time limit, localities can offer short-term emergency rental assistance through locally funded tenant-based rental assistance programs to forestall eviction. Some localities with access to more financial resources may offer long-term rental assistance to some income-qualifying households and specific target population groups to prevent homelessness. All forms of tenant-based rental assistance can be used to help protect residents at risk of eviction due to rising rents, but certain forms (such as the federal Housing Choice Voucher program) require property owner’s participation, so they may be more difficult to employ when the owner is seeking to move existing residents out.

- Homebuying assistance programs: Beyond ensuring basic housing stability, anti-displacement policies can also help renters build wealth through property ownership. Localities can help renters overcome credit and down payment barriers to purchasing a home in their neighborhood. These programs often must work with a family for several years to support them in buying a house in a neighborhood with high real estate and housing demand. Localities may consider implementing these programs early on in low-income neighborhoods and for any qualifying households across the jurisdiction.

Steps for homeowner protection

Low-income homeowners are often priced out of their homes long before they can realize the full gains from increased property values due to rising property taxes. In some cases, rising property taxes also may make it difficult for homeowners to afford to invest in the maintenance of their properties. Anti-displacement strategies can protect homeowners by reducing the impact of increased property taxes, thereby giving them greater choice over whether to stay in their homes or sell and leave.

- Reduce/defer property tax burden: Localities can institute policies to provide property tax relief for income-qualifying long-term homeowners in multiple ways. They can institute measures to set limits on property-tax increases, offer homestead exemptions that exclude a share of the home value from property tax calculations, or defer the collection of increased property taxes until the resale of the property.

- Financial assistance: Localities can provide financial assistance to help families avoid foreclosure. They can also help homeowners create additional revenue resources by facilitating the creation of ADUs on their older-single family homes. To help families access these resources, they can provide housing counseling to help families apply for loan modifications, refinancing, and homestead exemptions and facilitate the ADU process by offering pre-permitting meetings and design reviews.

- Legal assistance: Localities can also offer legal services to contest foreclosure orders and assist victims of predatory lending. For example, the City of Philadelphia passed an ordinance creating protective measures against property soliciting and creating licensing procedures for property ‘wholesalers.’

- Home repair and modification loans: Home repair loans and modifications grants to low-income homeowners can help homeowners address code violations, reduce energy costs, and create safe and age-friendly homes.

When property values increase, there is often a corresponding increase in homeowners’ property taxes. When faced with rising property values, long-term homeowners with limited incomes often face a difficult choice between finding a way to pay the increased property taxes necessary to stay in their home or selling their property before they are ready to do so. In addition to depriving long-term residents of a meaningful choice about whether to stay in their home, this choice may end up forcing residents with limited incomes to sell their house early in the cycle of home price increases. Early sales can deprive homeowners of the greater financial benefits that would follow if they were to stay longer and experience more home price appreciation. In some cases, rising property taxes also may make it difficult for homeowners to afford to invest in the maintenance of their properties. Without regular maintenance and energy-efficient upgrades, they may also face substantial energy costs. Poor habitable conditions can force homeowners to sell their homes. In extreme conditions, homeowners may default on mortgage or property tax payments and face foreclosures.

Homeowners are constitutionally eligible for homestead tax exemptions in many states that allow for the exclusion of a portion of the value of a home from property taxes or a lower rate for principal residences. Some states also protect homeowners by placing limits on property tax increases; this can take several forms, including a limit on the amount by which a property tax assessment may go up in a year.

The following are some key steps to protect homeowners:

- Reduce property tax burden: Localities can institute policies to provide property tax relief for long-term homeowners in multiple ways. However, they may require state authorizations to implement such policies to provide targeted relief to low-income homeowners.

- Circuit breakers: Localities can set limits on property-tax increases for qualifying households, sometimes called “circuit breakers,” to cap the amount of property taxes homeowners must pay as a share of their income.

- Homestead exemptions: Homeowners can also benefit from homestead exemptions that exclude a share of the home value from property tax calculations. Localities can offer these exemptions prorated based on homeowner income.

- Defer property tax payments: Localities can defer the collection of property tax increases until resale of the property to release long-term residents from undue tax obligations when they lack the means to pay for them.

- Financial and legal assistance: Where homeowners are already facing the threat of foreclosures due to mortgage non-payment and tax delinquency, localities can provide financial assistance to help families avoid foreclosure, provide housing counseling to help families apply for loan modifications and refinancing, and homestead exemptions, and legal services to contest foreclosure orders and assist victims of predatory lending.

- Accessory dwelling units (ADUs): Localities can amend their zoning code to allow ADUs in their single-family zoning by-right and provide necessary financial and technical assistance to help owners add ADUs to their properties. ADUs can help protect long-time homeowners by creating additional revenue sources while preserving their older-single family homes and can be an economical way for localities to increase their low-income housing stock. Generally, ADUs are not rent-restricted and do not fall under the purview of fair-housing law, and localities may not be able to effectively tailor them to meet the needs of lower-income households and other protected groups.

- Home repair and modification loans: Localities can offer home repair loans to low-income homeowners to address code violations, reduce energy costs, and create safe and healthy homes for their families. Aging homeowners can access loans or grants that help rehabilitate their homes with accessibility improvements and stay in them longer.

Steps to help displaced residents

An important aspect of addressing displacement is to help residents transition to their new homes when displacement cannot be prevented. Relocation assistance may be provided to families moving to a different home within their current neighborhood or another neighborhood of their choice. Localities can build support for relocation as an additional feature within many of the policy instruments described above in the ‘protect’ category.

- For example, displaced renters can benefit from a requirement for rental property owners to pay a relocation allowance built into rent stabilization programs when they are forced to move. Localities may also use locally controlled funds to cover moving costs and security deposits for relocated tenants, either as part of an ongoing rental assistance program or as a separate initiative. Homeowner relocation assistance programs can offer to pay inspection costs and mortgage transfer and lending assistance to enable homeowners to find structurally sound and safe housing options of their choice. Housing counseling and advisory services can help families locate new homes and assist moving households in filling out paperwork, setting up utility connections, and providing information related to school enrollment to help ease the relocation process.

Some localities have also instituted community preference policies designed to help displaced renters and homeowners find housing within their neighborhoods. Such policies dedicate a percentage of subsidized housing – either ownership or rental units – for individuals from the neighborhood and its adjacent areas or to individuals who can show strong ties to the community based on a set of qualification criteria. San Francisco’s policy is illustrative.

Community preference policies can be controversial because of their potential to have a disproportionate and exclusionary effect on people of a particular race or ethnicity. Disparate impact analyses, such as one conducted by San Francisco, can help localities assess the extent to which this is a problem. Some community preference policies, such as Portland’s N/NE Preference policy, take a reparative justice approach that addresses historical displacement due to public projects. However, such policies may not serve the immediate housing needs of families just displaced or at imminent risk of displacement.

Preserve

Objectives

- Preserve existing subsidized rental housing developments and prevent their loss due to owners opting out of subsidy programs in order to raise rents.

- Preserve older market-affordable housing units and reduce the likelihood they exit the affordable housing stock due to dilapidation, demolition, or redevelopment.

- Temporarily stem rent hikes in the market (or unsubsidized) affordable housing by helping small property owners to operate their properties profitably.

Preserving the existing stock of affordable housing in a neighborhood is often more economical than developing new affordable housing. Preservation of existing subsidized housing can be an important strategy in neighborhoods that are experiencing or expected to experience displacement pressures due to rising housing costs. Efforts to maintain the older housing stock of unsubsidized market units with low rents (which we call market affordable properties) are most useful early in the cycle of rising rents and increasing demand.

Subsidized units remain the primary focus of housing preservation policies since they often serve extremely low-income families earning below 30 percent of the median income. However, a large share of affordable rental housing units are privately owned non-subsidized units that are mainly filtered-down older housing stock with fewer amenities. In neighborhoods witnessing increased demand, owners of these private properties are often keen to reposition their property for higher rents by upgrading or redeveloping and alternatively converting them into condominiums and selling.

Anti-displacement preservation approaches require timely intervention to preserve affordable housing before rents and displacement pressures grow to a level where it is not financially feasible to intervene. Localities often take these steps in anticipation of the loss of affordable housing stock due to market pressures.

Steps for affordable housing preservation

Localities can pursue a range of approaches to facilitate the preservation of different types of affordable housing stock. They can provide incentives to encourage existing property owners to continue operating their units at affordable rates or directly intervene to acquire and transfer properties at the risk of being upgraded and repositioned for higher rents. As a less significant measure, some localities may also choose to disincentivize redevelopment to stem the loss of affordable housing stock.

- Groundwork for preservation strategies: As a first step, localities may want to assemble preservation inventories with geotagged data about the existing stock of subsidized housing and the state of their repair, ownership, and general operations. Where practical, developing an inventory of notable market affordable properties in at-risk neighborhoods may also be useful. Given the difficulty in assembling such information for market affordable housing, localities may benefit from building a network of community liaisons and ground-level staff in at-risk neighborhoods who can interact with property owners and tenants and report real-time conditions.

- Incentivizing preservation: Localities can provide operating and repair grants and loans and property tax incentives to enable owners of subsidized rental properties to extend the affordability period of their units without selling or exiting the subsidy programs. Similarly, localities can work with public housing agencies to improve the physical conditions of public housing stock and preserve their longevity through the Rental Assistance Demonstration program and other federal programs. For small-scale owners of market affordable housing, localities can provide financial counseling and facilitate access to small-scale loans as temporary preservation measures to delay the repositioning of market affordable housing to appeal to higher-income households.

- Acquisition: Localities or their mission-driven partners can strategically approach and buy both subsidized and market affordable properties that are in good structural condition in order to ensure their continued operation with affordable rents. Localities may institute policies that require longer notice periods or invoke right of first refusal policy to give tenants and other mission-driven property owners a chance to buy the property where property owners have already decided to sell.

- Disincentivizing redevelopment and demolition: Localities sometimes disincentivize avoidable redevelopment and demolition to stabilize neighborhoods experiencing rapid change in built environment and loss of affordable housing units. For example, they can levy demolition taxes and condominium conversion fees to make unnecessary demolitions cost-prohibitive for the property owners. They may also impose land use regulations that restrict redevelopment using historic district designations or conservation overlays to prevent the loss of single-family homes. However, such regulations may often cause more harm than good by constraining supply and contributing to increases in prices.

The following is a list of policy options to consider for preserving existing affordable housing in neighborhoods experiencing rapid increases in rents and home prices:

- Preservation inventories and outreach: An important initial step to preserving the existing stock of dedicated affordable housing is to assemble data regarding the existing subsidized affordable housing stock. (See the National Housing Preservation Database). Many localities may have ready access to housing databases of subsidized projects with basic information regarding the number of housing units and the income groups they serve. However, details regarding the upkeep of property, possible code violations, and expiring affordability periods are not always available.

While it may not be practical to develop a parallel list of all unsubsidized properties that are affordable throughout the entire locality, it may be useful to develop such a list for vulnerable neighborhoods to add information about viable private stock for preservation. Localities may benefit from community liaisons and ground-level staff who can identify these properties at the neighborhood level and interact with property owners and tenants to identify their concerns and possible solutions to prevent the loss of at-risk properties.

In many cases, preservation will require mission-driven partners – either nonprofits or mission-driven for-profits – who can take over the maintenance and operation of preserved units for long-term affordability. Equipped with the preservation inventory and information on the capacity and priorities of their mission-driven partners, localities can develop a list of priority properties for preservation and work to assemble the resources and enlist owner cooperation. - Incentivizing preservation

- Subsidized housing:

- Operating and repair grants and loans: To enable owners of existing subsidized rental properties to continue to operate their units without selling or exiting the subsidy programs, localities can provide support to these owners to meet financial needs for repair and maintenance. Some localities provide direct grants or loans to help these owners address priority needs in exchange for long-term extension of affordability. These investments can help extend the affordability period of existing subsidized properties or, at a minimum, slow the immediate exit of rent-controlled units from the subsidized housing inventory.

- Tax incentives: As with owners of single-family homes, owners of multifamily rentals often face an increased property tax burden due to the rise in their property values. Similar to repair loans, property tax incentives to subsidized property owners who agree to preserve their properties as affordable can help retain and extend the affordability period of existing subsidized housing.

- Market affordable housing: When rents and property values are rising, small-scale owners of market affordable housing may seek out opportunities to sell their properties to larger owners who have the resources to reposition them for higher rents. Localities can delay this repositioning of market affordable housing by helping small-scale rental property owners operate profitably. Localities can provide financial counseling and facilitate access to small-scale loans to market affordable housing that owners can use for maintenance and repair as temporary preservation measures.

- Public housing: Maintaining public housing units in neighborhoods subject to displacement pressures can be critical for localities looking for ways to preserve existing affordable housing inventory in such neighborhoods. Unlike subsidized and market affordable housing properties, the primary concern with preserving public housing developments is generally not how to keep them affordable but instead how to maintain these properties in adequate physical condition. Localities can work with public housing agencies to facilitate the preservation of public housing units through the Rental Assistance Demonstration program and other federal programs.

- Dedicated funding sources for preservation: Preservation efforts require a reliable and dedicated means of funding. To ensure dedicated funding streams and to supplement overall budgetary dedications for preservation, localities can earmark all or a portion of increased property tax receipts from designated neighborhoods to be reinvested within the designated boundaries toward preservation initiatives. (Tax Increment Reinvestment Zones in Houston provide an example of this approach, as a portion of TIF revenue must be spent on affordable housing).

- Subsidized housing:

- Acquisition:

- Buying properties: Localities or their mission-driven partners can strategically approach and buy both subsidized and market affordable properties that are in good structural condition in order to ensure their continued operation with affordable rents. Such acquisitions can require quite a lot of capital up front but can serve long-term needs with minimal subsidies when run by mission-driven owners or managers. One way to facilitate this acquisition is for localities to give priority in approving gap financing for Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) deals to applicants who are opting to purchase and renovate an older subsidized property over projects in other parts of the city.

- In instances where property owners have already decided to sell or reposition their property for higher rents, localities may institute policies that require longer notice periods or invoke right of first refusal policies to give tenants and other mission-driven property owners a chance to buy the property and preserve its affordability.

- Public-land banks: Localities may acquire vacant lots and dilapidated properties that require demolition to create public land banks for future development of subsidized housing. This option is most applicable to neighborhoods that have not yet experienced significant increases in property values, as rising property values make the likelihood of a distressed property without a market buyer less likely.

- Disincentivizing redevelopment and demolition: Localities sometimes seek to stabilize neighborhoods experiencing rapid change in the built environment and the loss of affordable housing units by disincentivizing avoidable redevelopment and demolition. However, unless paired with sufficient incentives to help repair and maintain existing affordable housing units in good condition, such regulations might cause more harm than good by stalling construction activity and further constraining supply. Some interest groups may also take advantage of these preservation tools to keep neighborhoods segregated.

- Land use restrictions: Many localities use historic districts or conservation overlays to preserve the historic character of the neighborhoods (See Seattle’s Pike/Pine Conservation Overlay District) by imposing higher standards of setbacks, building code regulations, and lower allowable heights than the baseline zoning norms in the jurisdiction. The intent of these overlays is to prevent the loss of older single-family housing to demolition and discourage new developments that may not conform with existing neighborhood character. While such policies can sometimes delay redevelopment of older single-family homes, they don’t necessarily prevent home values from rising and can sometimes lead to unanticipated changes, such as increases in the share of homes that are rented out.

- Demolition taxes and condominium conversion fees: Localities can levy taxes on property owners when they tear down buildings or opt to convert rental units into condominiums. Localities can build conditions into the fee structure to make avoidable demolitions cost-prohibitive for the owners. Any accruing revenue from such fees can be reinvested into neighborhoods for the preservation and rehabilitation of affordable housing.

Produce

Objective

- Encourage targeted production of dedicated affordable housing units in areas experiencing or projected to experience rising rents and home prices through new construction or the acquisition (and often the rehabilitation) of existing properties.

To help ensure that people of all incomes can continue to afford to live in neighborhoods subject to displacement pressures, it will be important for an anti-displacement strategy to encourage the targeted production of dedicated affordable housing in these neighborhoods. Such targeted production can help relocate displaced low-income residents within their neighborhoods and create opportunities for other low-income residents to move into and enjoy the benefits of these neighborhoods. The production of dedicated affordable housing can involve the construction of new units but also includes efforts to bring existing unsubsidized units into the affordable housing inventory with legally binding affordability stipulations.

Steps for new construction

Localities can promote construction of new affordable housing units in target neighborhoods through a combination of tools, including:

- Gap financing: The most common approach to producing new dedicated affordable housing is through the use of housing subsidies (such as LIHTC). These projects often require local contributions to close the gap between project costs and available funding, giving localities the opportunities to prioritize affordable housing projects proposed in at-risk neighborhoods for their gap financing support.

- Tax abatements: Localities can offer tax abatements for new multifamily housing projects in exchange for including a predetermined number of affordable housing units in new developments.

- Inclusionary zoning: Localities can require or create incentives for private developers to include rent-restricted or deed-restricted ownership units in new developments through Inclusionary zoning policies. Whether voluntary or mandatory, inclusionary zoning policies often provide developers incentives in the form of increased densities, fast-tracked permit processing, or reduced parking minimums in exchange for the inclusion of dedicated affordable ownership or rental units.

- Publicly-owned land: In some instances, localities can leverage public land to incentivize the production of dedicated affordable housing in mixed-income developments.

The following are examples of ways to support new construction in targeted areas:

- Using subsidies to produce new dedicated affordable housing: Localities can use housing subsidies (such as federal low-income housing tax credits) to produce dedicated multifamily affordable housing through new construction. Often these projects will require gap financing from locally controlled funding sources, so prioritizing areas at risk of displacement for these resources is one way to encourage the development of additional dedicated affordable housing in these areas. Since buying land in areas at risk of displacement can be costly, localities should consider developing on publicly owned land where available.

- Tax abatements for multifamily development: Localities can offer tax abatements for new multifamily housing projects in exchange for including a predetermined number of affordable housing units in new developments. Tax abatements can be attractive to developers since they reduce property tax liability significantly in the initial project phase. However, they are typically offered for only a defined period (such as five, ten, or fifteen years) since they may significantly reduce a locality’s tax base.

- Inclusionary zoning policies are popular tools for capturing increases in land value attributable to zoning changes to facilitate development (such as upzoning). Localities can adopt an inclusionary zoning policy that requires a share of new development to be affordable. This can be instituted citywide or in certain targeted areas, such as areas subject to displacement pressures related to rising housing costs. Inclusionary housing policies can be mandatory or voluntary policies. In either case, most localities offer developers incentives in the form of increased densities, fast-tracked permit processing, fee waivers, reduced parking minimums, or other forms in exchange for the inclusion of price-controlled ownership or rental units. Some localities also offer additional financial incentives to developers, such as cash grants or tax abatements to create deeply affordable housing with long-term price controls.

Steps for converting existing housing stock into dedicated affordable housing

Localities can produce dedicated affordable housing through the acquisition and rehabilitation of existing housing by intervening early in the cycle of housing price increases to implement policies such as the following:

- Financial assistance: Localities can support applications by developers or property owners for tax credits and tax-exempt bonds to acquire and rehabilitate existing rental properties to create additional rent-restricted units by bringing them into a housing subsidy program. Localities can also facilitate the purchase of low or moderately-priced market-rate properties or tax-delinquent properties by mission-driven owners to be operated charging below-market rents. As short-term measures, localities can partner with public housing agencies to encourage project-based rental assistance to specific properties in target neighborhoods. Such measures help convert an existing unsubsidized unit into a subsidized unit using Housing Choice Vouchers.

- Promoting community ownership: Localities can encourage the creation of Community Land Trusts (CLTs) and other forms of shared equity homeownership to maintain long-term affordability for income-eligible homebuyers. Localities can donate land or buy properties to be placed under community ownership or deed restrictions to help start such initiatives. To make homeownership affordable in the long term, localities can ensure that property taxes are levied on the property’s legally restricted sales prices rather than the full market values.

In addition to building new homes, localities can produce dedicated affordable housing through the acquisition and rehabilitation of existing housing. It can be helpful to undertake such initiatives proactively, early in the cycle of housing price increases, to avoid competing with market investors in hot real estate markets. Localities can also create dedicated affordable housing units through the project-basing of Housing Choice Vouchers in existing housing units.

- Converting market-rate rental properties: Localities can support applications by developers or property owners for LIHTC funds and tax-exempt bonds to acquire and rehabilitate existing rental properties to create additional rent-restricted units by bringing them into a housing subsidy program. As with new construction, such projects often require gap financing from locally controlled funds. Localities can also facilitate the purchase of low or moderately-priced market-rate properties or tax-delinquent properties by mission-driven owners, who agree to operate the units as rent-restricted even without a subsidy-related affordability requirement. Such initiatives are likely to be most cost-effective early in the cycle of neighborhood change, before rents and property values rise substantially.

- Project-based rental assistance: Public housing agencies (PHAs) have the ability to attach (project-based) federal Housing Choice Vouchers to specific properties, converting an existing unsubsidized unit into a unit with a deep rental subsidy that adjusts for families’ incomes. This approach is most likely to be successful early in the cycle of rising rents and property values, before property owners’ expectations for rent have grown too high. However, PHAs that are open to adopting Small-Area Fair Market Rents or other approaches for raising maximum subsidy levels to better respond to local variations in rent, may have success even after rents have risen somewhat. This approach is also generally limited to fifteen-year contracts, so it’s not a long-term solution. However, such initiatives can serve as important short-term measures as the locality works to arrange other long-term affordable housing options.

- Community Land Trusts (CLTs) and other forms of shared equity homeownership use community ownership of land or deed restrictions to maintain long-term affordability for income-eligible homebuyers. Localities can encourage the creation of CLTs by donating land, buying properties to be placed within a CLT, or providing subsidies to CLTs or other shared equity homeownership programs to facilitate their purchase and construction or rehabilitation of homes. Some CLTs also own units they rent out affordably. Localities often offer property tax relief for owners of CLT or other shared equity homes to help make homeownership more affordable and ensure that property taxes are based on the restricted sales prices permitted for the properties rather than full market values. Because this form of homeownership ensures homes stay affordable over the long term, they can be important tools to preserve the inclusion of low- and moderate-income households in neighborhoods experiencing housing cost increases. Some CLTs, such as the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative in Boston, MA, have also been used to help preserve ethnic neighborhoods and promote community cohesion and cultural stability.

Examples

- Austin, TX: Austin’s Displacement Mitigation Strategy brief was prepared within their overall local housing plan, the Austin Strategic Housing Blueprint. The brief outlines 15 displacement mitigation strategies derived from more than 300 community recommendations. The 15 strategies are aligned with their Community Plan and the local housing strategy based on the overall objectives and identified community values to provide short-term priorities for city action.

- Seattle, WA. Seattle prepared a comprehensive list of displacement risk indicators and identified possible data sources for tracking displacement and its disparate impact on racial and ethnic minority groups by combining data from discrete sources. The planning commission’s issue brief, Addressing Displacement in Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan offers detailed guidance and recommendations for incorporating anti-displacement objectives and strategies in Seattle’s ongoing major comprehensive plan updates.

- San José, CA. San José Citywide Residential Anti-Displacement Strategy was prepared by the City as part of its Housing Crisis Work Plan. The strategy outlines 10 recommendations and supporting actions to “prevent, mitigate, and decrease” displacement in San José based on the 3P anti-displacement framework. The draft strategy was amended to include unique displacement risks posed by the pandemic and its uneven impact.

- Portland, OR. A strategic planning exercise for updating Portland’s Comprehensive Plan brought the City and community together in finding strategies to prevent displacement in Portland. The Gentrification and Displacement study and ongoing consultations with the community resulted in several city housing and planning initiatives to address displacement. Portland has recently adopted the Anti-Displacement Action Plan to take stock of previous efforts and to coordinate and develop strategies for the future.

Related resources

- All-in Cities Policy Toolkit. An initiative of PolicyLink, the All-In Cities Toolkit offers actionable strategies that advocates and policymakers can use to advance racial equity.

- Gentrification Response: A Survey of Strategies to Maintain Neighborhood Economic Diversity. This NYU Furman Center report covers strategies that have been used to create more affordable housing and assist low-income households at risk of displacement because of rising rents.

- National Housing Preservation Database (NHPD). The NHPD is an address-level inventory of federally assisted rental housing in the U.S.

- Preserving and Expanding Affordability in Neighborhoods Experiencing Rising Rents and Property Values. This journal article published in Cityscape addresses comprehensive strategies local governments will need to adopt to preserve and expand housing affordability.

- Reducing Poverty Without Community Displacement: Indicators of Inclusive Prosperity in U.S. Neighborhoods. This report by Brookings discusses neighborhoods that have succeeded in reducing poverty without displacing residents.

- The Urban Displacement Project (UDP) is a research and action initiative of the University of California Berkeley and the University of Toronto.

1 Many housing and anti-displacement toolkits employ the 3P framework, notably, The Urban Displacement Project and the Alliance for Housing Justice. Variations of the 3P’s framework are also seen in the housing plans and anti-displacement strategies of the cities of Oakland, CA, Seattle, WA and Charlotte, NC, among others.

While the origins of the framework are unclear, sources point to its possible emergence from the Committee for Housing Bay Area (CASA) compact (https://mtc.ca.gov/sites/default/files/CASA_Compact.pdf) that finalized a 10-point set of policy recommendations using the 3P’s framework. The 3P’s framework has provided the overarching support for many recent bills passed by the California State Legislature.