Housing Solutions Lab

Helping cities plan, launch, and evaluate equitable housing policies

On this page

California legalized ADUs. But unpermitted ones are still far more common, new research finds.

June 4, 2024

By Ben Hitchcock

Even as California has tried to make building legal accessory dwelling units as easy as possible, a new study suggests that, in San José, more than 1,000 unpermitted ADUs were constructed in a four-year period—reflecting the state’s severe housing shortage and underscoring the urgent need for affordable housing options.

The image shows an accessory dwelling unit, or ADU. Both permitted and unpermitted ADUs have grown in San José, CA, in recent years, demonstrating the need for affordable housing. Image credit: Sightline Institute. CC by 2.0.

Property owners in San José, one of the largest cities in northern California, legally built about 291 detached ADUs from 2016 to 2020, according to a paper by a team of Stanford University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) researchers supported with a grant from the Housing Solutions Lab. But by employing a computer vision model, human annotations on a stratified sample of parcels, and publicly available satellite imagery, the authors estimated that 1,045 (±226) additional informal detached ADUs were built during the same time period.

“Our limited understanding of informal ADUs may distort our assessment of the effects of ADU liberalization,” wrote Nathanael Jo, Andrea Vallebueno, Derek Ouyang, and Daniel E. Ho in their paper, titled Not (Officially) in My Backyard: Characterizing Informal Accessory Dwelling Units and Informing Housing Policy with Remote Sensing. “We have developed a rigorous, cost-effective, and flexible methodological framework that enables the measurement and characterization of the complete detached ADU stock.”

Three of the researchers are at Stanford’s Regulation, Evaluation, and Governance Lab, and the paper was published this week in the Journal of the American Planning Association (JAPA).

Unpermitted ADUs are most likely to be located in dense, diverse, overcrowded communities, the authors found. The prevalence of these informal units reflects the dire shortage of housing options in California, and in vulnerable neighborhoods especially. The study also highlighted the challenges homeowners face in navigating complex rules and regulations to add ADUs to their properties and called for continued efforts to reduce obstacles to legal ADU production.

Legal ADUs are still hard to build

ADUs are widely recognized as an effective way to create affordable housing, and in 2016, California passed ambitious legislation to remove regulatory barriers that were slowing down ADU production. After the laws took effect, production took off: just over 1,000 ADUs were permitted in 2016, and over 24,000 were permitted in 2022, about 19 percent of all new housing permits. In San José, where the study focused, the number of legal ADU constructions has increased thirty-fold.

However, previous research has also demonstrated that, even after California’s 2016 policy changes, homeowners still have to navigate a complex set of rules and regulations before they can add ADUs to their properties (Chapple et al., 2021; Greenberg et al., 2022; Volker & Handy, 2023).

“Cost is likely a dominant barrier that drives homeowners towards informal ADU development,” the authors of the new paper write. For example, in San José, fees related to permit issuance, plan review, and inspections currently range from approximately $3,000 to $4,700. Such fees may inadvertently push people to develop informal ADUs rather than going through existing official channels, according to the authors.

Unpermitted ADUs can pose serious policy challenges. They do not undergo proper building, fire, and health code inspections and therefore may constitute unsafe, substandard housing. Unaccounted-for units can strain or overwhelm city services. Tenants living in unpermitted ADUs live with a high eviction risk, since they could be forced to move if the units are discovered. But crafting policy around unpermitted ADUs has been challenging for policy leaders, in part because detached ADUs are often concealed in backyards or otherwise difficult to identify.

How many unpermitted ADUs are there, and where are they located?

To locate and characterize informal ADUs, the study authors first gathered satellite imagery from the National Agriculture Imagery Program and building footprints from OpenStreetMap. They then trained a computer model to identify residential parcels with a high, medium, or low likelihood of having new detached constructions. Finally, they engaged third-party human reviewers to review over 15,000 parcel images and explicitly label detached structures that appeared habitable. Buildings smaller than 250 square feet were excluded from the analysis to filter out sheds, carports, and small offices.

From this labeling procedure, the authors estimated that about 75 percent of detached ADUs were unpermitted. They then analyzed the differences in neighborhood and parcel characteristics between formal and informal ADUs, and discovered that unpermitted ADUs were not evenly distributed across demographics and neighborhoods.

Homeowners who were more likely to build unpermitted, detached units tended to be less wealthy, as measured by property values. These homeowners were also more likely to live in neighborhoods with a lower proportion of white households, higher density, and greater overcrowding.

While using this innovative ADU detection technique, the researchers carefully preserved the anonymity of informal ADU owners and inhabitants. They only presented aggregate statistical results and released an imagery dataset that completely excludes informal detections. In the paper, the writers emphasized that this technique should be used “to inform the design of equity-driven policies that focus on communities rather than specific non-compliant homeowners, and generate supportive resources rather than disciplinary actions.”

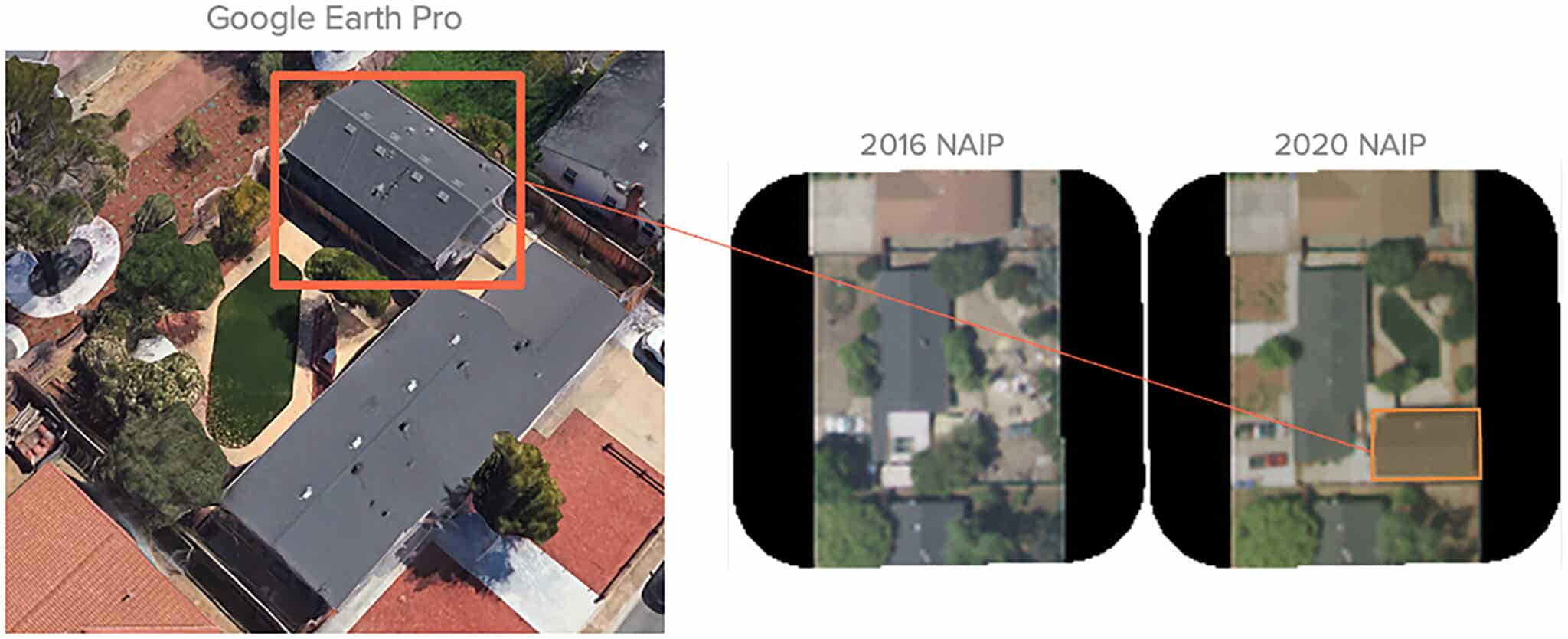

Figure 2. Example of a permitted detached ADU built during 2016–2020. On the left, a 3D visualization of the ADU and the parcel in which it is located using Google Earth Pro; on the right, the annotated National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP) imagery from 2016 and 2020 for the parcel, including an orange polygon around the ADU in 2020. (Google Earth, Citation 2022; Earth Resources Observation and Science Center, Citation 2022).

What does this tell us about the housing crisis?

In the absence of policy solutions, communities may assert more of their own agency in addressing the housing crisis than policymakers realize, write the authors. The number of unpermitted ADUs may reflect the desperate need for new housing in low-income, diverse neighborhoods. Residents appear willing to assume the risks of building and living in informal housing to avoid the shock of displacement or homelessness.

Other factors may also contribute to the uneven distribution of informal ADUs across homeowner and neighborhood demographics. As previously mentioned, the ADU permitting process can cost thousands of dollars in legal fees. People of color often face the most persistent barriers and discrimination in accessing financing, and immigrant communities may experience information gaps about local building codes and permit requirements. Additionally, zoning ordinances could disproportionately restrict ADU development options in certain communities.

The researchers argued that governments and policymakers should continue to lower barriers to legal ADU production. ADUs contribute much-needed affordable housing supply, and legalizing them has real safety benefits for residents. There are direct benefits for the city governments, too: San José, for example, has only met 26 percent of its state-mandated housing construction goals, but if all the informal ADUs captured by the satellites had been permitted, the city could have reported significantly more new housing construction.

Moving forward, outreach programs, amnesty programs for legalizing existing informal ADUs, and permit process improvements could be valuable to municipalities and tenants. “Local enforcement should strive to directly address the underlying barriers to legal ADU construction,” the authors write, “rather than the symptoms stemming from these barriers.”

For questions about this research, contact Derek Ouyang, Research Manager at the RegLab, which is based at Stanford University.